Forest Service, Fairchild solve mystery of plane crash discovered in the Colville National Forest

Lt. Dallas Sartz, left, and Lt. Hal Morrill pose at the crash site in 1955. (Courtesy of Fairchild / Courtesy of Fairchild)

Maj. Charles Seeley had just completed a turn after his fourth pass of the “enemy target” and was in a controlled dive when the F-86A Sabre jet started to buck.

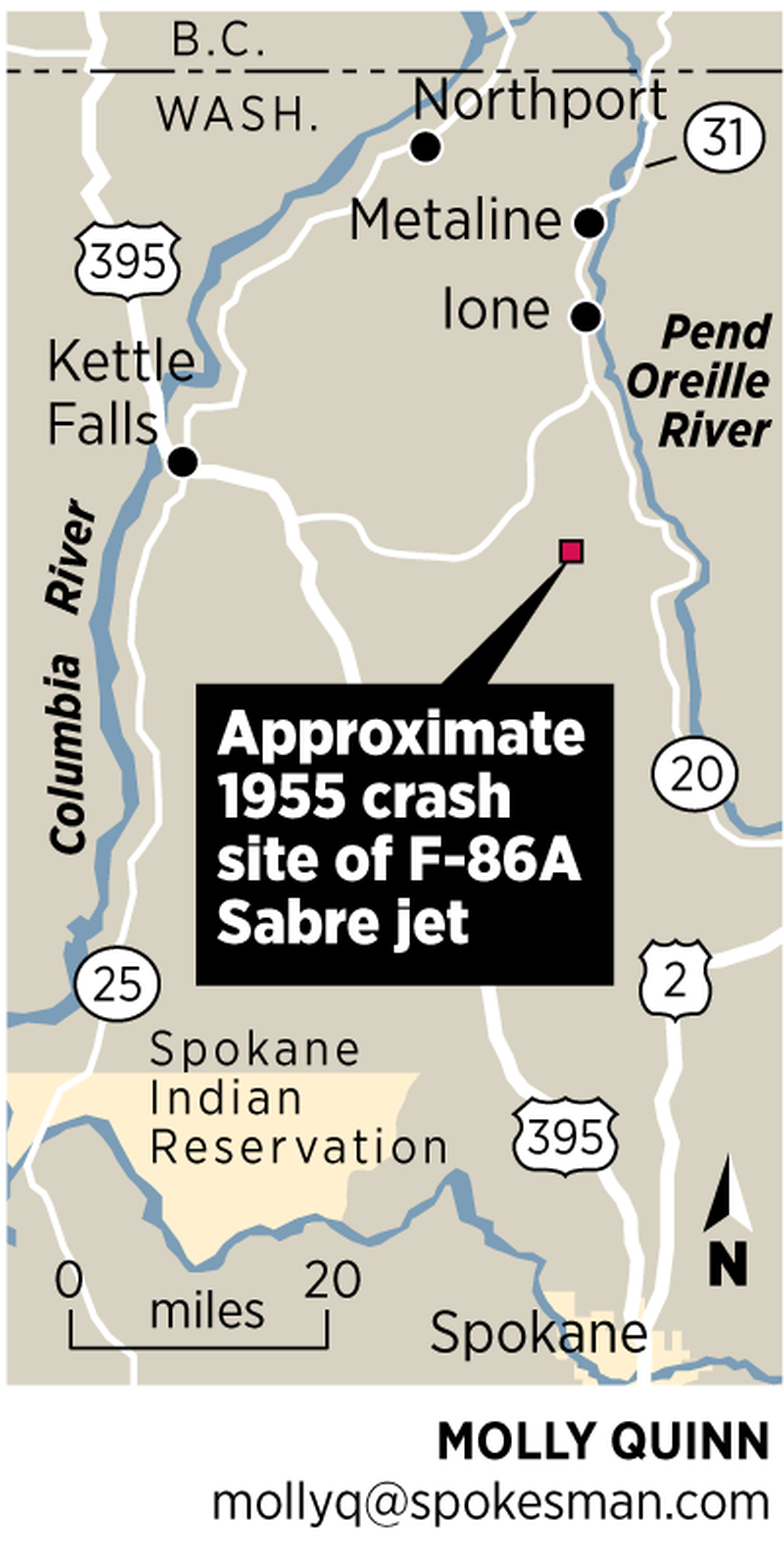

Seeley, the executive officer of the Washington Air National Guard’s 116th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, was a member of a four-jet practice flight about 21,000 feet above northeastern Washington. Practicing maneuvers against a B-29, the jets “attacked” it from above and behind.

The flight had been smooth after the jets scrambled off the runway at Geiger Air Field. But Seeley, at 37 a veteran pilot of World War II, had made some adjustments with the rudder and ailerons to keep his plane, serial number 48-292N, level.

At 300 knots – about 345 mph – the plane began rolling violently to the left. Seeley cut the throttle and tried several maneuvers, but the plane continued to roll. As it gained speed and rolled below 12,000 feet into the thick clouds, he determined there was no choice but to eject. The mountainous ground below, where the peaks were about 6,800 feet, was coming up fast.

He pulled the lever once, twice and a third time before the canopy blew off. It glanced off his helmet, and Seeley shot out of the Sabre at 10,000 feet. His parachute opened and he began floating down through the clouds. It was March 23, 1955.

Crashes common

About two years ago, a survey crew from the U.S. Forest Service was checking a remote drainage area of Timber Mountain in the Colville National Forest south of Ione, Washington, when they made an unexpected find.

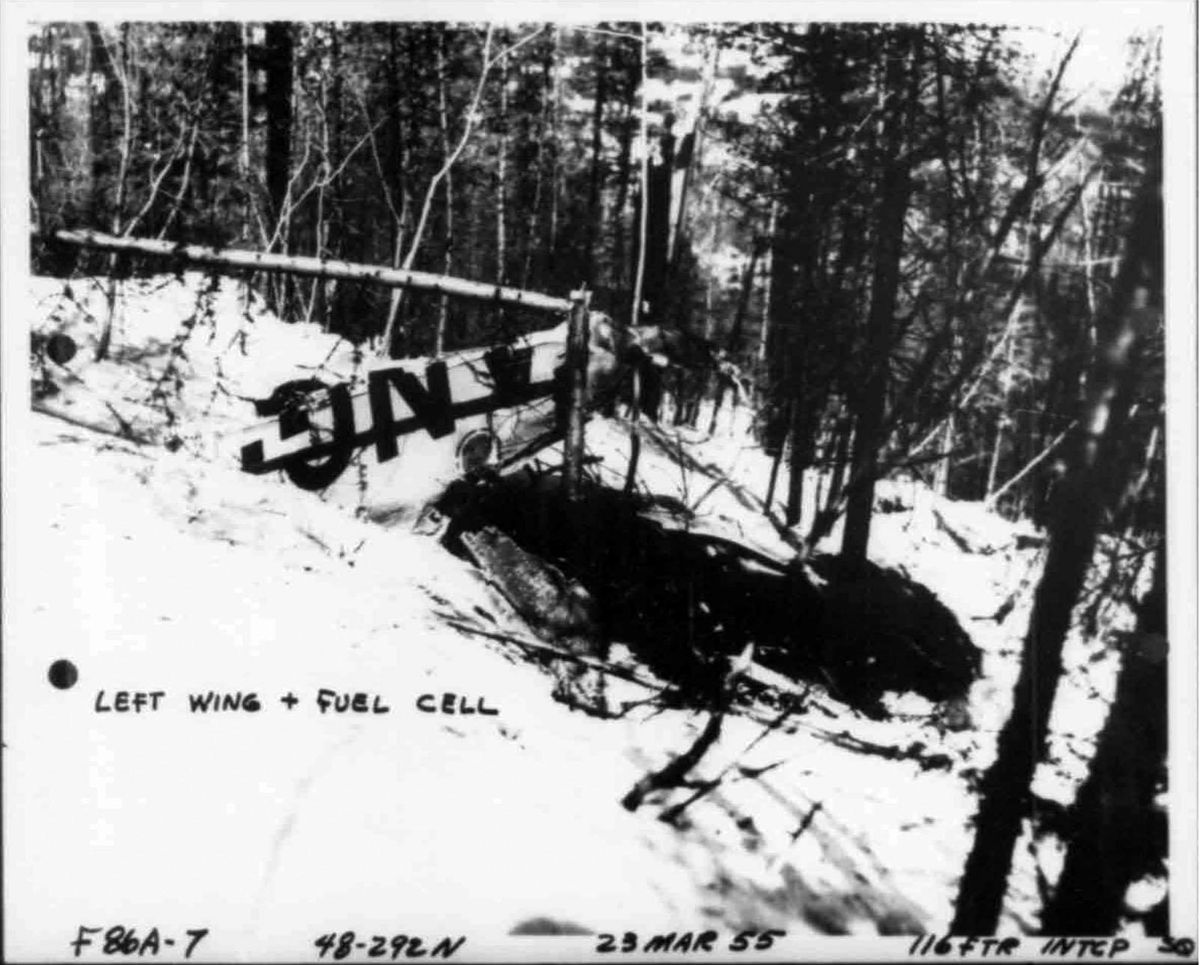

Twisted wreckage of some type was showing among the stands of 85-year-old timber, and had been there long enough for trees to grow around and through it. Closer inspection showed it was an airplane, with what seemed to be machine guns among the debris, clearly military.

How long it had been there, the crew wasn’t sure. Forest Service records had no mention of a military plane crash in that section of the Colville, but the crash appeared to be from a time when records weren’t kept as carefully as they are now.

Forest Service officials were more curious than surprised, said Franklin Pemberton, a spokesman for the Colville National Forest. “Every national forest I’ve ever worked in has one or two plane crashes. We didn’t know we had one in that area,” he said.

The service sent out the Colville National Forest’s archaeologist to survey the site. Like many national forests, the Colville has numerous sites that were occupied by Native American tribes, as well as old homesteads and even some abandoned machinery from small mills. Archaeologists scout areas for historic significance before roads are built or timber is offered for sale.

The area is so remote that hikers or hunters are unlikely to come upon it, Pemberton said. But there was a concern: If those were machine guns in the wreckage, does that mean there would also be ammunition, and perhaps even bombs?

In checking the records, they discovered a major fire burned through the area in 1929-30, Pemberton said, so they knew the plane crashed after that. Because it was a military plane, they called contacts at Fairchild Air Force Base, which regularly uses the Colville for part of its survival training. Eventually they connected with Jim O’Connell, the 92nd Air Refueling Wing historian.

In, out of the forest

Maj. Seeley floated down into the forest below the clouds, where his parachute got hung up in a tree. He managed to make it to the ground, which was covered with about 3 feet of snow. That March was one of the region’s coldest on record and Seeley wasn’t in his winter gear, but he started walking in what he thought was the direction of a logging road he spotted during his descent.

After about a half mile, he told The Spokesman-Review for the next morning’s paper, he found the road, and a short time later a logger in a truck found him. The logger took him to a branch road, and a bulldozer mechanic took him to Newport.

By the time he reached Newport, members of the Air National Guard had arrived to take him to the hospital at Fairchild. He was bruised from the ejection, but the next day he told reporters the worst effect was a stiff neck.

By then, search teams had spotted the crash site in the deep snow on a mountainside, and one pilot from the training flight who had also gone to Newport to pick up Seeley, 1st Lt. Hal Morrill, would accompany investigators to the wreckage.

A recent phone call

Morrill was at home in northeast Spokane recently when he got a call from Fairchild Air Force Base, asking if he was the same Hal Morrill who was a pilot in the Washington Air National Guard in 1955. He said he was. Was he on a flight over northeastern Washington when another plane crashed? Yes, he said.

Morrill had received his wings in 1949 and worked full time at the Guard as a flight training supervisor in 1955 when he flew on the training mission with Seeley, squadron commander Maj. Charles Nelson and Lt. Leo Arnold. He was mentioned in the story of the crash in The Spokesman-Review.

That allowed O’Connell to track him down more than 60 years later. O’Connell and others from Fairchild visited the site in early July with a Forest Service team and were able to identify the plane from markings that were still visible. Matching those numbers to the Aviation Archaeology website with information on almost all military crashes, O’Connell had a date. He checked the Google News Archive for the next day’s Spokesman-Review and got the report of the official crash investigation.

Morrill left the guard in 1957 for a career in the Civil Aeronautics Administration, and retired from its successor, the Federal Aviation Administration. At 88, he’s the sole remaining member of that mission and “I’m still hanging in,” he said.

He remembers the F-86 fondly as a beautiful plane: “For the time, it was like a Cadillac.”

The nation’s first swept-wing jet fighter, the Sabre, also known as a Sabrejet, was the dominant plane of the Korean War, with a maximum listed speed of 687 mph and six machine guns in the nose. Its pilots shot down 792 MiGs while losing only 78 Sabres, and all but one of the U.S. pilots who achieved the status of ace flew the F-86. After the war, it became a mainstay of Air Guard fighter units, which the 116th was at the time.

Morrill remembers the mission and Seeley going into a rapid, spinning descent. “Then I lost him in the clouds and didn’t see the airplane hit.”

But a few days later, Morrill saw the crash site. Someone took a picture of him and another officer standing in front of the crater the jet made when it hit.

“We went in on snowshoes, it was so rugged,” he recalled.

In the snow they found a wing, the engine and debris scattered over a wide area. But he could definitely put to rest any fears by the Forest Service that the plane may have carried ammunition or bombs. There wouldn’t be any for a training mission, he said, something the accident report O’Connell obtained confirms.

Likely cause

The Air Force convened an investigation board, interviewing Seeley and other pilots on the flight as well as other officers.

Less than two weeks later, it released its conclusions: Seeley had done everything possible to recover from the spin, and stayed with his aircraft as long as possible under the circumstances. The plane may have had a structural defect that caused it to go into the uncontrollable roll, but the board couldn’t be sure because 48-292N was too badly damaged in the crash.

Pilots in the fighter wing were ordered to abort flights in their F-86s when similar situations occurred, and safety directors were asked to contact headquarters about possible maneuvers to pull out of the roll. Two weeks later, another pilot in the wing had an almost identical experience in another F-86, but was able to pull it out before the jet reached an agreed-upon bailout altitude of 8,000 feet. An investigation showed there were short-circuits in some of the aileron switches in the cockpit.

The investigation board ordered the Washington Air Guard to send a team back to the wreckage site “as soon as snow conditions permit” to see if more could be discovered about the cause of the crash. There’s no record of whether they made the trip, but if they did, the terrain was likely too steep and access too difficult to remove the pieces.

Having lain on the side of Timber Mountain for more than 60 years, the Forest Service and the Air Force are not going to disturb the wreckage of 48-292N. It’s now an archaeological site, and they won’t put up a marker or reveal the exact location, to keep souvenir hunters from trying to hike in and pull out pieces.