This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Shawn Vestal: Shortage of legal aid tips the scales of justice against the poor

When I was about 15, I went with my mother to court to deal with one of many problems that had been dumped in her lap by my father.

It was a civil matter, a question of a debt. We met in the judge’s chambers at the county courthouse. I don’t recall many details, but I distinctly remember my mother’s emotional state: humiliated, ashamed, frustrated and angry.

She is a smart and capable woman, but she was in no position to be her own most effective legal advocate.

Was the justice she obtained in that room the same that was available to everyone? Or did she get what she paid for when she represented herself?

I ask this in light of an item in Gov. Jay Inslee’s proposed 2018-19 budget: A proposed increase in funding for legal assistance for poor Washingtonians, who are second-class citizens before the law. Large majorities of low-income households face serious legal issues each year, and large majorities do not seek or receive the help of an attorney.

Washington’s judiciary and lawmakers started to get serious about legal aid for the poor in 2003, when a task force was formed to investigate the problem. In the intervening years, and especially since the recession, resources have dwindled. Staffing cuts have resulted in a drop of “20 percent of our client service capacity,” said James Bamberger, director of the Office of Civil Legal Aid.

With a new legislative session looming, the sides are already arguing over proposed tax increases and the state Supreme Court’s languishing McCleary order for lawmakers to do their job on funding schools. The final budget probably won’t look much like Inslee’s proposal, and the battle to come will be one of attrition, a narrowing sense of “priorities,” and the continual drumbeat Bamberger characterized as “McCleary, McCleary, McCleary, McCleary.”

“There’s this list of unaddressed, high-priority state budget issues,” Bamberger said this week. “The question that always comes up is, ‘Where does legal aid fit onto that list?’ ”

Bamberger’s office, which is overseen by a committee of lawmakers and judges, has proposed a 49 percent increase in funding for legal aid services, and Gov. Jay Inslee included it in his budget proposal. The office had a $26 million budget in the last biennium; the new proposal would raise that to $41 million, mostly directed toward expanding legal aid staffing.

This would go toward correcting a glaring imbalance: On everything from employment discrimination to housing fairness to debt collections to bankruptcy to foreclosures, poor Washingtonians have little access to the system that is meant to protect their rights.

It’s tempting to say this is unacceptable. After all, if our system of justice doesn’t work for everyone, it’s not a system of justice. It’s something else entirely. But we accepted this long ago, in many ways and with eyes wide open. There’s even a term for it, one that gets used in annual reports emerging from Olympia, year after year: the “Justice Gap.”

The state Supreme Court, in its annual “State of the Judiciary Report” for 2016, said it was time for a “recommitment” to closing that gap. Year after year, the state has made little progress. A 2015 update of the original 2003 report found that the situation had worsened in some respects: 71 percent of low-income households in the state experienced “profound” civil legal problems and three-quarters got no legal help. In the 12 years between reports, the average number of legal issues each household experienced in a year rose from three to nine.

And yet most do not have access to even limited legal services, which can help greatly. The survey showed that of the minority of respondents who got legal help, 61 percent said it helped resolve the issue either completely or somewhat.

The consequences of legal assistance can be life-altering, as Jed Rakoff, a federal judge, wrote recently in the New York Review of Books:

“In mortgage foreclosure cases, for example, you are twice as likely to lose your home if you are unrepresented by counsel. Or to give a different kind of example, if you are a survivor of domestic abuse, your odds of obtaining a protective order fall by over 50 percent if you are without a lawyer.”

Does that sound just? Or just mercenary?

“We must recognize the consequences of a system of justice in our state that denies a significant portion of our population the ability to assert and defend their core legal rights,” said Supreme Court Justice Charles Wiggins, who chaired the task force that produced the report. “We can and we must do better.”

Will we? The bipartisan committee that oversees Bamberger’s office has a plan: If the Legislature doesn’t bolster legal aid through the general fund budget, they’ll seek a tax – a “civil justice surcharge” on legal services of half of 1 percent. That would be $5 on a $1,000 legal bill, or $50 on a $10,000 bill.

It’s the committee’s way of refusing to let the problem die on the doorstep of McCleary.

“They’re very serious about making sure we don’t lose the energy or the focus on addressing the serious problems documented in that study, simply because there are other profound budget challenges for the state,” Bamberger said.

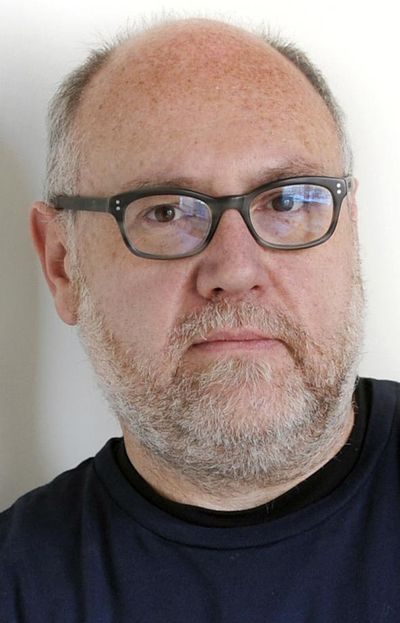

Shawn Vestal can be reached at (509) 459-5431 or shawnv@spokesman.com. Follow him on Twitter at @vestal13.