Keeping my promise: A personal Pearl Harbor reflection

Stretching out, I pressed my cheek into the hot sand, its gritty heat almost too much to bear. Closing my eyes, I imagined the shriek of airplane engines and the spitting sound of machine gun fire hitting the beach, while the air around me burned.

I covered my head with my arms, and could almost hear the whistling sound of bullets whizzing past my ear.

A shadow loomed. “Are you okay?” my husband asked.

Slowly, I sat up and scooted back onto my brightly-colored beach towel.

“Just thinking about Nick,” I said, while I slipped on my sunglasses.

The beauty of being married 30 years is I didn’t have to explain what I meant.

Derek and I visited Oahu in March to celebrate our anniversary, but the trip was part pilgrimage for me. After nine years of interviewing Pearl Harbor survivors, I was at last visiting the place I’d written about so often.

Here on Waikiki, I was just 12 miles away from Hickham Field where Nick Gaynos almost lost his life on Dec. 7, 1941.

During the attack on Pearl Harbor, Nick had been running toward his duty station when a Japanese pilot targeted him. He’d told me of looking up as he ran and seeing the grin on the pilot’s face as he fired at him.

Nick hit the beach and covered his head with his arms as the bullets flew. When he got up he discovered a large piece of shrapnel next to him.

“I grabbed it,” he said. “It was still hot from the explosion.”

When my book “War Bonds: Love Stories From the Greatest Generation” was released, Nick attended a reading at the Coeur d’Alene Public Library in March 2015. He brought that piece of shrapnel with him. It was jagged and more than 2 feet long. He died a few weeks later.

Now, on the island that had been so devastated by the horrific attack, I carried his memories with me as well as those of Warren and Betty Schott. The Schotts had quarters on Ford Island and were eyewitnesses to the attack.

When Derek and I walked through the entrance of the Pearl Harbor Visitor Center, I wanted nothing more than to talk to Betty, to tell her I was here. But Betty passed away in July 2015.

At the center, we watched a short film featuring actual footage of the attack. A scene of sailors and soldiers pulling the wounded and dead from the harbor made me gasp. That’s what Warren had done in the aftermath – it was the one thing he didn’t want to discuss with me over the course of many interviews. It was the only thing he refused to speak of with his wife of 76 years. Now, watching the footage through tear-filled eyes, I finally understood why he was loath to speak of it.

That horror was also all too real for my friend Ray Daves. During the attack, he hustled to a rooftop and handed ammo to two sailors who were manning a .30-caliber machine gun. He had his own brush with death when a Japanese plane exploded 20 feet from that rooftop before crashing into the sea below. His left hand was lacerated by shrapnel.

Like Warren Schott, Ray spent time pulling wounded men from the harbor, his blood mingling with the red splashes in the water around him. In his biography, “Radioman,” he described the bodies and body parts floating in the harbor. “We had to push them aside to get to the wounded,” he said.

Despite those gruesome memories, what really choked him up was recalling the bombing of the USS Arizona.

“My friend George Maybee was on the Arizona,” Ray said. “We’d gone through radio school together. Sat beside each other every day and were bunkmates at night.”

“My friend George Maybee was on the Arizona,” Ray said. “We’d gone through radio school together. Sat beside each other every day and were bunkmates at night.”

He watched as the Arizona burst into a huge fireball. He knew his friend was gone.

Over the years, Ray and I grew close. He reminded me so much of my dad. They were both from Arkansas and had joined the military seeking a way out of the poverty of the rural south. Both had tender hearts and shared a wickedly funny sense of humor.

The last time I spoke to Ray before his June 2011 death, I told him I longed to visit Pearl Harbor.

“George is there,” he said, his eyes filling.

“I’ll look for his name,” I said. “I’ll say a prayer.”

Ray took my hand. “You do that, sweetheart.”

Five years later, I boarded the boat that took us to the USS Arizona. As we stepped from the boat onto the memorial, the throng of tourists quieted. The only sound was the snapping of the flag in the wind and the clicking of cameras.

We were somber with the knowledge that we were standing on the final resting place of 1,102 of the 1,177 sailors and Marines killed on the Arizona.

A rainbow of undulating color in the water below caught my eye. Some 500,000 gallons of oil are still slowly seeping out of the ship’s submerged wreckage, and it continues to spill up to nine quarts into the harbor each day.

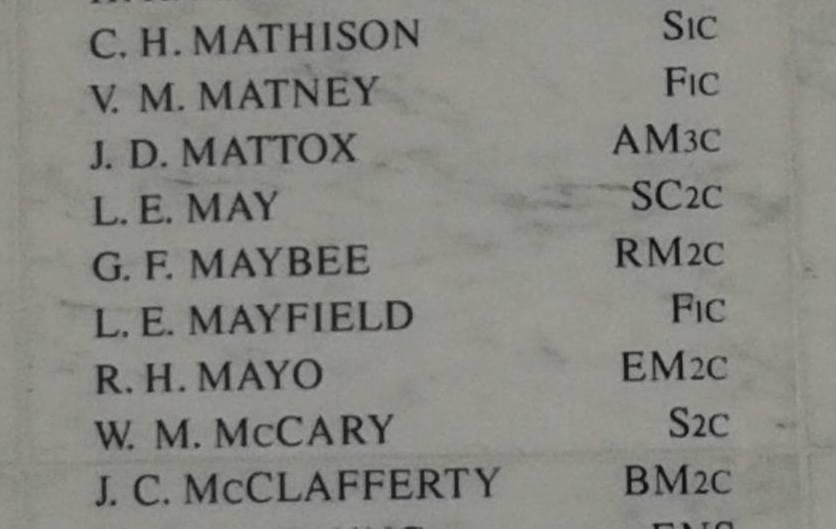

Slowly, I entered the shrine. A marble wall bearing the names of those entombed beneath us stretched out behind a velvet rope.

So. Many. Names.

Overwhelmed, I looked at Derek. “I’ll never find him,” I whispered.

The day had been overcast, but suddenly a shaft of sunlight illuminated the marble.

“There,” Derek said. “There he is – G.F. Maybee.”

Bowing my head, I wept for the sailor I’d never met and for my friend who knew and loved him.

I hope that somehow Ray knows I kept my promise.

George Maybee hasn’t been forgotten. Neither has Ray Daves.

For more on this story

Visit Remembering Pearl Harbor