After veto, Idaho moves to allow 25 sick kids access to cannabis-derived drug

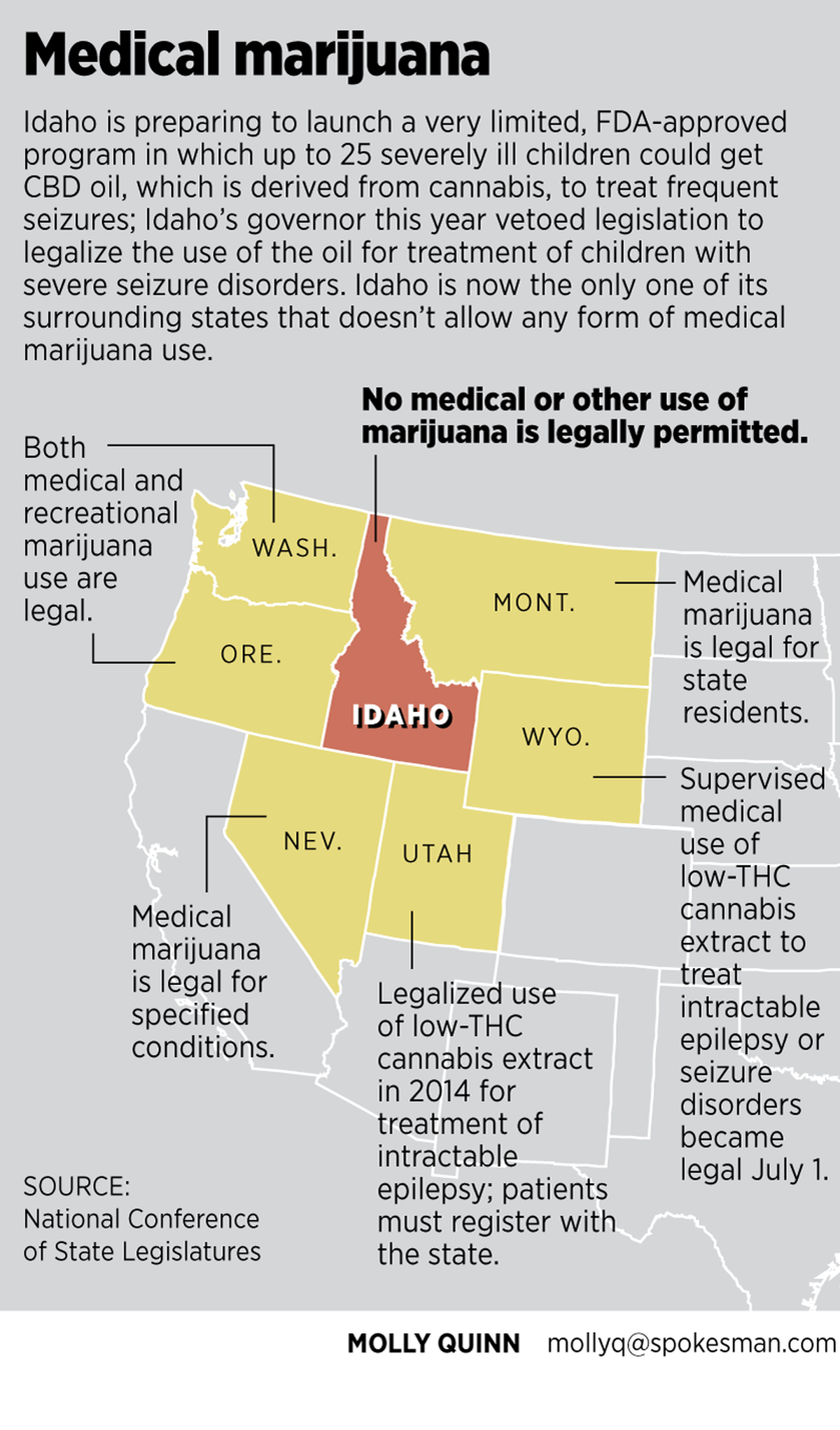

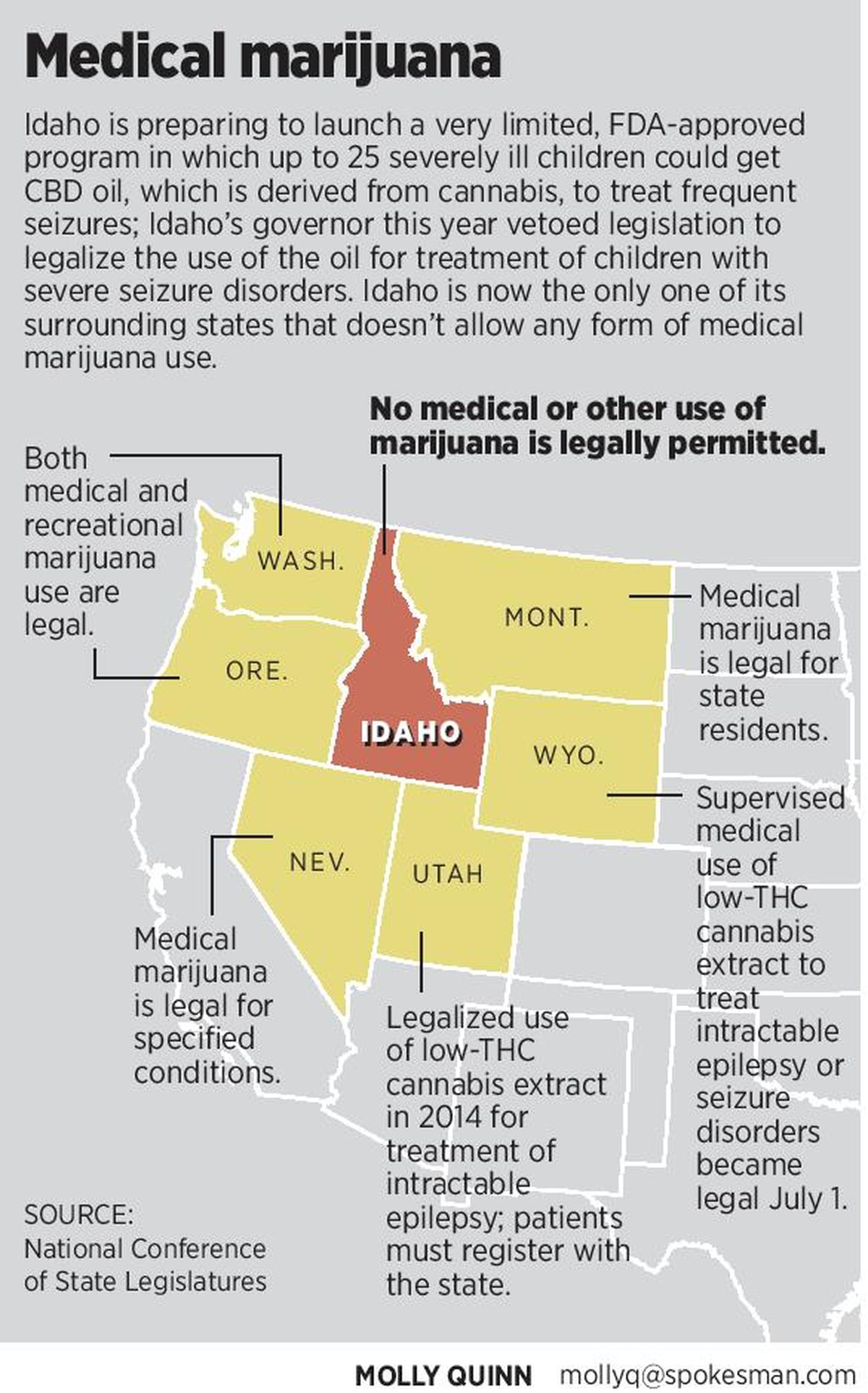

(Graphic by Molly Quinn)

BOISE – Idaho is just weeks away from enrolling up to 25 children with severe epilepsy in a free program to provide them with an experimental, non-psychoactive drug extracted from marijuana, under an executive order from Gov. Butch Otter.

But estimates of the number of children eligible for the program are much higher – 1,500 or more. Only Idaho children who have tried at least four different medications but still suffer at least four seizures a month are eligible.

Idaho “doesn’t track children with epilepsy, we don’t have a firm number on that,” state epidemiologist Dr. Christine Hahn told state lawmakers. “It’s not completely clear how many children would qualify, but I think many more than 25.”

Otter signed his executive order in April after vetoing legislation that would have allowed the use of cannabidiol, a low-THC oil extracted from cannabis, to be used legally in Idaho to treat children with severe seizure disorders. The measure passed both houses after long and emotional hearings, but Otter’s Office of Drug Policy and the Idaho State Police decried it as a step toward legalizing medical marijuana.

Idaho is now alone among all its surrounding states in banning any form of marijuana use, for medical or other purposes. Wyoming this year legalized the supervised use of cannabidiol oil, also called CBD oil, to treat intractable epilepsy or seizure disorders; Utah did the same in 2014. In 2013, the Idaho Legislature overwhelmingly passed a resolution against ever legalizing any form of marijuana use for any purpose.

“Idahoans are not afraid of being different than their neighbors,” said Elisha Figueroa, director of Otter’s Office of Drug Policy. “I think that they are wanting to protect their way of life. And so just because our neighbors choose to go down one road does not mean that we will automatically go down that road, if we don’t feel like it’s the appropriate one for us.”

Figueroa said she supports the new, limited distribution program.

“This is really what we want to see happen, is that we follow the approved FDA process to ensure that medications that we receive have gone through the proper vetting process,” she said.

Claire Carey, whose 10-year-old daughter Alexis has suffered seizures since she was 2 months old, called the process “frustrating.”

“They’re helping 25 children at most. … It just made me lose all hope. The only way we are going to get access in Idaho is with a federal bill,” she said.

Parents who filled legislative hearings this year described in heart-wrenching detail what it was like to see their young children wracked by seizures that even strong drugs, with multiple side effects, couldn’t stop. Many said they’d heard of others who found relief for their kids through the use of CBD oil. One dad told lawmakers his daughter was having 200 seizures a day until he began treating her with the oil and her seizures stopped, and she was taken off all her other medications; at that point, she hadn’t had a seizure in 30 days.

Otter, in his veto message on the CBD oil bill, wrote, “Of course I sympathize with the heartbreaking dilemma facing some families trying to cope with the debilitating impacts of disease.” But he said the bill raised too many questions for law enforcement and other officials.

“It asks us to legalize the limited use of cannabidiol oil, contrary to federal law,” the governor wrote. “And it asks us to look past the potential for misuse and abuse with criminal intent.”

The oil that will be used in the FDA-approved but closely limited Idaho program is Epidiolex, a cannabis-derived product developed by a British pharmaceutical firm. It’s currently in clinical trials in various locations around the United States; as part of that, the FDA allows a small number of patients to receive it outside the trials, so the child runs no risk of receiving a placebo instead of the real drug. It’s a program that previously was called “compassionate use.” It’s now dubbed “expanded access.”

An Idaho physician who is involved in the clinical trials of the drug has received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to run an “expanded access” program for up to 25 children in Idaho, Hahn said. The doctor, Robert Wechsler, of Boise, has now applied to the U.S. Department of Justice for modification of his Drug Enforcement Administration certification, because any cannabis-derived product is considered a Schedule 1 drug, the most closely regulated type, under federal law.

“We are now waiting,” Hahn said. “They have acknowledged receipt, and they have four weeks to approve it. That is the last hurdle, and as soon as that approval is received and his DEA license is expanded to include the use of this medication for this purpose, we can start enrolling patients.”

The state Department of Health and Welfare has contacted every neurologist in Idaho to alert them about the program and the possibility of enrolling their young patients, Hahn said. “We believe the word is getting out.”

She noted, “We have permission to only enroll 25 children, although some estimates are that there are many more who would potentially qualify.” Among qualified children recommended by their neurologists, she said, “It’s kind of first come, first served.”

Hahn said the department has been using funds from within its budget to start up the program, but it will request funding from the Legislature in the coming legislative session.

When lawmakers asked her if there were any income restrictions for eligibility for the program, she said no, “because cost is not the issue. You could have all the money in the world and not purchase this legally at this time.”