Police whistleblower complaint raises questions about department’s seizures

An investigation into an apparently illegal seizure of more than $13,000 cash from two suspected drug dealers by a Spokane police detective last year shows tension among police brass over a civil forfeiture unit created under former police Chief Frank Straub.

A whistleblower complaint filed by Lt. Joe Walker last November against his supervisor, Investigations Capt. Eric Olsen, alleges Olsen minimized or covered up the seizure instead of promptly returning the cash, a claim Olsen said is absolutely untrue. A city investigation into the complaint, conducted by independent attorney Thomas McLane, found Olsen did nothing wrong, though it did not rule on whether the search was legal.

Detective Joe Pence searched the car of two suspected drug dealers on Sept. 2, 2014, without a warrant and seized $13,250 in cash. That cash eventually was returned to the man it belonged to on Jan. 12, nearly two months after Walker filed his complaint. Olsen said delays in returning the cash were because Pence and his supervisor didn’t promptly follow his orders to return the money to the suspects.

“I said we’re giving the money back. I was very clear in my direction,” Olsen said.

Pence was counseled, but never disciplined, for conducting the search without a warrant, and the department did not conduct an internal affairs investigation into the seizure. Pence, through a department spokeswoman, declined to comment on the whistleblower complaint or the seizure.

Through a public records request, The Spokesman-Review got a copy of the whistleblower complaint, which includes copies of department policies, memos, meeting minutes and emails between police brass and city attorneys.

Pence got a search warrant for a car belonging to Daniel Gonzalez and Freddy Vasquez, two suspected drug dealers living in the Yakima area, after an informant allegedly bought heroin and meth from the men on Aug. 20, 2014, in Spokane, court documents say. Pence arrested Gonzalez and Vasquez that day on suspicion of selling drugs.

Court rules in Washington say a search warrant must be executed within 10 days after it’s issued by a judge. Pence searched the car Aug. 21 but had a suspicion he missed something, according to information in an unrelated internal investigation file.

He went back and searched the car, which remained in police custody, a second time with a drug dog on Sept. 2, after the original warrant had expired. During the second search, Pence found the cash in a hidden compartment of the car and seized it. Gonzalez and Vasquez were mailed notice the same day that their cash had been seized.

Court records show the men were never charged with a crime in connection with the case. Both were released from jail on bond, and those bonds were exonerated on Sept. 16, 2014. Still, the police department held on to their cash.

Phone numbers listed as belonging to Gonzalez and Vasquez in court records were disconnected or belonged to people who said they did not know the two men.

A unit for forfeitures

Walker’s complaint and supporting documents show dissent in the ranks about a department push under Straub to seize assets used in the commission of drug crimes and felonies.

Under Washington law, law enforcement officers can seize someone’s property, including cash and vehicles, if there’s evidence it was used to commit felony or drug crimes. For a felony seizure, the person must be convicted before they forfeit their property.

Under the drug law, police need only probable cause to believe the property was used to commit a drug crime. The suspects do not need to be convicted, or even charged, for their property to be seized and forfeited. If they want their property back, they have 45 days to request a hearing to contest the seizure, which is conducted by the city’s hearing examiner. If the examiner sides with the police department, the property is forfeited and police can use it or sell it at auction.

Straub created the department’s Civil Enforcement Unit, which handles asset forfeiture and works on abandoned properties, last year. Unit members say their goal is to target the root issues of crime – removing cash and other valuables that make it easier for drug dealers to continue operating, and shutting down problem properties where drug users and chronic offenders congregate.

Asset forfeiture has long been supported by law enforcement agencies across the U.S. that say it’s a powerful tool for combating drug crime. Forfeiture can also be a moneymaker for departments.

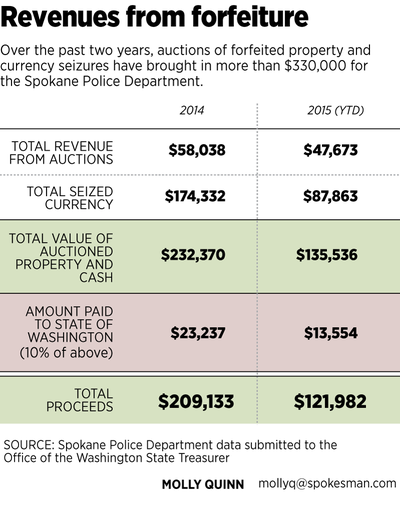

In 2014, the Spokane Police Department deposited nearly $157,000 in seized cash and sold more than $50,000 of other forfeited items at auction, according to reports the department submitted to the state treasurer’s office. So far this year, the department has deposited more than $120,000 in seized cash and auction proceeds.

State law restricts how those funds can be spent. Money seized from drug forfeitures only can be used to enforce drug laws, for example. Olsen said all seized funds are used to further law enforcement activities and said he welcomed further inquiry into how seizure funds are used.

“I have nothing to hide. The CEU has nothing to hide,” he said.

In a July 9, 2014, meeting, Straub discussed the new unit with police brass. Meeting minutes, paraphrasing the former chief, said about asset forfeiture: “We are missing it on the felony side” and “It is also an opportunity to bring money back into the department.” Straub assigned Walker to lead the unit.

Walker said statements and emails included in his complaint show there was a push to seize assets for revenue.

“That’s not what this unit should be set up for,” he said.

Police department policy sets a minimum value for seizures, but it’s significantly lower than the threshold used by the Department of Justice in federal law enforcement. In Spokane, cash seizures must be worth at least $100, and vehicles at least $1,000. The federal minimum is $5,000 for both cash and vehicles, unless the person has been arrested – then it’s $2,000 for vehicles and $1,000 for cash.

Olsen said those lower thresholds reflect the fact that federal law enforcement agencies tend to go after bigger crimes than local police.

“They’re dealing with a different type of crime,” he said. But others in the department say local guidelines should mirror federal ones.

“When we first started being part of that, setting it up, we wanted to mirror what the federal agencies used as guidelines,” said Walker, referring to some police leadership involved in the unit. “We were overruled on that.”

Capt. Brad Arleth represented the Lieutenants and Captains Association on the whistleblower panel for Walker’s complaint and agreed with Walker’s view that Straub’s unit was created to bring in revenue.

He said asset forfeiture can be a useful law enforcement tool, but articles written by the Washington Post documenting problems with federal asset forfeiture programs last year showed that it’s important for departments to be careful with what they seize.

“Local law enforcement agencies have to be very judicious in what they’re taking from people, and I think the standards should be set at at least what the federal government is comfortable with,” he said. “I think a lot of times what we might see in this community is we’re seizing things that are of less value.”

Department records show many forfeited items auctioned off by the department in 2014 were low-value: $24 in jewelry from a 2013 case, an $8 police scanner seized in 2012. Cash seizures from 2014 and 2015 were usually more than $1,000, though a few are below the department’s current $100 threshold.

After the search

Walker’s complaint said he found out about Pence’s $13,250 seizure from another detective. He emailed Olsen on Sept. 3, 2014, saying he believed the expired search warrant created legal liability for the city and department.

“I don’t feel we have the legal ability to seize this cash and our only option is to return the cash to the legal owner,” the email said.

Olsen told Walker he’d take care of the issue. He said he directed Pence and his supervisor to return the cash as soon as he learned about the seizure.

In late October, Walker discovered while he was cleaning out old cases that the cash was still being held as a seizure. Olsen said he didn’t realize the cash hadn’t been returned yet until Walker brought it to his attention.

“I found that out, and I was upset,” Olsen said.

Walker’s complaint also said Pence filed an additional report describing his Sept. 2 search of the car as an inventory search, which is designed to record what’s in a vehicle, not look for evidence. It’s a categorization Arleth and Walker both said was inaccurate.

“There was no valid search warrant so there was no reason to be digging around with a drug dog at that point for an inventory search,” Arleth said.

After learning the cash still hadn’t been returned, Olsen asked Walker to list the cash as “found property” in the department’s property management database so that it wouldn’t be accidentally seized. Walker made the change because he was asked to, but said the property should have been listed under “safekeeping,” because found property can be claimed by the department if it’s not picked up within a certain amount of time.

“I said the appearance was that this entire incident was being covered up. I also told him that this Civil Enforcement Unit appears to have been created by Chief Straub as a revenue generator and this was a significant amount of cash,” Walker wrote in the complaint.

Records in the department’s property management system show Gonzalez picked up the cash on Jan. 12, 2015. By then, Walker had left the unit to return to patrol. He said he filed the whistleblower complaint to find out what happened to the cash and never got an answer until The Spokesman-Review looked into the issue.

Olsen said Walker’s complaint and attachments contained a number of facts. “Most of them are true. However, the picture they paint is absolutely false,” he said.

Pence’s warrantless search was reviewed by the chain of command, but was not forwarded to Internal Affairs for further investigation.

“If it rises to the level of an Internal Affairs investigation, we would have taken it from there,” said Tim Schwering, the director of the department’s Office of Professional Accountability. “Schwering said he agreed with the decision not to forward the investigation because the chain of command review was ‘sufficient to address the issue.”

Olsen said Pence’s supervisor, Sgt. Brent Austin, also received a chain-of-command review for not returning the seized cash sooner and was disciplined, though he declined to say what discipline Austin received.

Detective Pence was counseled by Austin for conducting the search without a valid warrant, but no further investigation was done into the apparently illegal search. “The second search of the vehicle caused numerous legal issues for the seizure of the cash and narcotics located during the second search,” the documentation of that counseling says. It also says Pence “understood his mistake and took full responsibility.”

Less than a month after Pence signed a letter documenting that he was counseled about the improper search and seizure, he entered a vehicle being stored as evidence in a homicide case without a warrant and removed jumper cables to use on a department van. Schwering filed a personnel complaint about the Nov. 6, 2014, incident.

An Administrative Review Panel report on that case questions whether Pence learned anything from the prior illegal seizure. The report says Pence told internal investigators the earlier $13,250 warrantless seizure “wasn’t a big deal. It’s the first time I’ve been written up in 18 years so I let bygones be bygones on it.”

When asked by investigators what impact the counseling he was given played in his decision to enter the vehicle on Nov. 6 without a warrant, he said, “None.”

“It appears that Det. Pence did not view his original search as a violation, nor does he consider the current complaint a ‘search,’ ” the report says. As a result of Pence’s second warrantless search, the department spent $6,415 to install a new fence at the vehicle storage facility. Arleth and Walker both sat on the panel, though Lt. Steve Wohl wrote the report.

The panel concluded Pence “doesn’t get the seriousness of his actions” and recommended he receive one day off, be monitored closely and receive formal training. Olsen wrote him a letter of reprimand, which is included in the file.

A letter Arleth wrote on behalf of the Lieutenants and Captains Association after the city closed the whistleblower investigation echoes Walker’s allegations that Pence’s seizure was not addressed properly.

“The seizure discussed in the complaint was done without a valid search warrant, was therefore a 4th Amendment violation, and was not addressed as such,” the letter said. “The seized money should not have been retained after the first notification to Capt. Olsen as each commissioned law enforcement officer has taken an oath to uphold the Constitution.”

That oath means police need to be transparent when they make mistakes, Arleth said.

“If we’re trying to do what we’re sworn to do we’ve got to be accountable for it and we’ve got to do the right thing,” he said.

This article was updated on Nov. 1, 2015 to clarify comments made by Tim Schwering.