Avista explains need for another rate increase

Wendi Dunlap lives in a house in Hillyard with an old furnace. Last winter, the social worker qualified for energy assistance to help pay her Avista bill.

Many Spokane families are like hers – working, but struggling to make ends meet, Dunlap told an Avista executive at a recent neighborhood meeting.

“You’re constantly asking us to open our wallets,” she said. “I didn’t get a raise last year or the year before.”

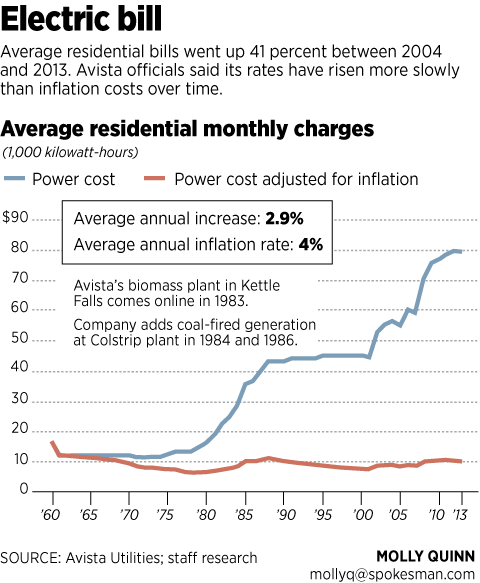

With the Spokane-based utility proposing its eighth rate increase in eight years, Kelly Norwood, Avista’s vice president for state and federal regulation, has been making the rounds of neighborhood association meetings to discuss the company’s request. If approved by Washington regulators, a typical Spokane household would pay about $140 more for electricity and natural gas each year, for an annual energy bill of about $1,940.

Norwood faced a polite but skeptical crowd earlier this month at the Northeast Community Center, located in a working-class neighborhood in north Spokane.

Why, audience members asked, does Avista need more money every year when many families are making do on the same income or less?

Norwood used charts and graphs to answer the question, emphasizing two points:

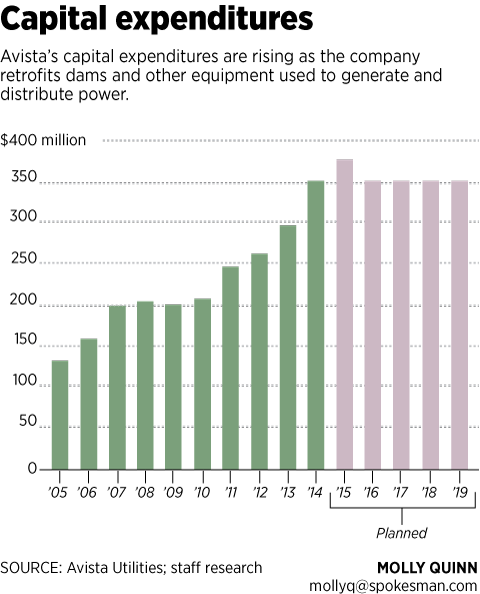

• The utility is spending hundreds of millions of dollars to upgrade aging dams, transmission lines, substations and other facilities that produce and deliver electricity and natural gas. Avista just finished major renovations at its Clark Fork River dams, which were built in the 1950s, and is now embarking on similar work at the company’s Spokane River dams, which date to the early 1900s. Much of Avista’s infrastructure was installed during the post-World War II era. It’s simply wearing out, Norwood said.

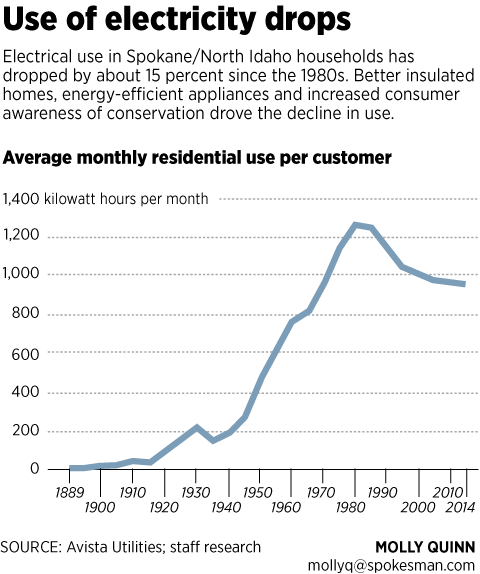

• The company’s revenues are relatively flat. Avista’s sales are growing at about 1 percent per year, partly because individual customers are using less energy. Since the 1980s, the amount of electricity consumed by households has dropped by about 15 percent. Better-insulated buildings, energy-efficient appliances and other conservation measures have contributed to declines in energy use.

The result, Norwood said, is Economics 101: Sharply higher costs are falling on a relatively static customer base.

The annual rate hikes come as a shock to many utility customers, some of whom remember that Avista raised rates only once in the 1990s.

Norwood said the company dynamics were much different in the past. From the 1950s through the early 1980s, Avista’s customer base was growing rapidly enough to absorb heavy capital investment with minimal impacts to rates.

During the 1990s, Avista was able to keep costs low by selling surplus electricity to California and the Puget Sound area. The excess energy came from contracts for cheap power from dams on the mid-Columbia River, but those contracts have since expired, Norwood said.

Avista expects yearly rate increases to continue, based on projected capital spending.

“We don’t see an end right now, at least for the next three to five years,” Norwood said.

Even with recent rate hikes, Norwood said, the utility’s rates remain competitive for the Northwest and the nation.

In Spokane, however, higher utility bills are affecting families feeling the pinch of stagnant wages. The city’s median household income of $47,500 has dropped nearly 10 percent since 2008, when adjusted for inflation.

Brooke Plastino, president of the Bemiss Neighborhood Association, said he appreciated the chance to talk about rates with a top Avista official. He’s been following recent headlines about higher pay for Scott Morris, Avista’s chairman and chief executive officer, and the company’s profitable year in 2014.

When Norwood asked to give a presentation at the neighborhood meeting, “I knew there would be some hard questions,” Plastino said.

Here are some answers to questions S-R readers have asked about how rates are set; how much profit the utility’s shareholders earn; and what’s ahead for ratepayers.

The rate process

Avista operates as a monopoly in its service area, with about 600,000 electric and gas customers in Eastern Washington, North Idaho and parts of Oregon. Since there’s no competition, Avista and other investor-owned utilities are regulated by commissions in each state.

When Avista wants to raise rates, it submits a proposal to the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission, or the Idaho Public Utilities Commission, which review the request and make a decision. The commissions are tasked with making sure utilities remain financially healthy while keeping rates fair and reasonable.

In Washington, residential and small business ratepayers also have an advocate in the state Attorney General’s Office of Public Counsel, whose attorneys review rate cases on their behalf.

Rate cases are complex legal proceedings; they take about 11 months in Washington and seven months in Idaho. The commissions and their staffs evaluate the costs the utility wants to include in rates and determine whether the costs are justified. Commissions also set the profit margin each company is allowed to earn.

“There are a lot of people who look at everything we’re doing to make sure that the rates are fair,” Norwood said.

In recent years, state regulators have been responsive to Avista’s requests for higher rates, granting at least a portion of each request.

Nationally, utilities are in a period of heavy spending to modernize aging infrastructure and improve the reliability of the electric grid, said Danny Kermode, acting policy director for the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission.

“These are huge costs,” said Kermode, noting that installing a mile of transmission line costs about $2 million.

Costs are rising faster than the equipment replacement values embedded in rates, which has led to sticker shock for utilities and their ratepayers, he added.

In 1960, for instance, Avista paid about $9 for each wooden power pole. Through their rates, customers paid off the cost of the pole over time. But as Avista replaces each 50-year-old pole, the company will pay $100 for the new ones. That’s part of the higher costs putting pressure on rates, Kermode said.

U.S. investor-owned utilities spent $450 billion on capital projects in 2013, according to the Edison Electric Institute.

“If you look across the country, other utilities’ rates are going up for the same reason,” Norwood said.

Kermode said Washington regulators are encouraging companies to become more efficient in order to soften the impact of capital spending on customer rates.

The shareholders

Through the sale of stock, Avista raises part of the money the utility uses to pay for capital projects. The company borrows the rest.

Avista has about $2.5 billion invested in dams, transmission lines, substations and other equipment that directly serves its utility customers. Shareholders financed about half of that infrastructure through their stock purchases and earnings that get reinvested in the company. They’re looking for a return on their money, Norwood said.

“We try to offer a return that is competitive with other companies,” he said.

Avista competes with other utilities and other industries for investors. Generally speaking, utilities attract shareholders looking for a lower-risk investment, such as pension funds, insurance companies and retirees.

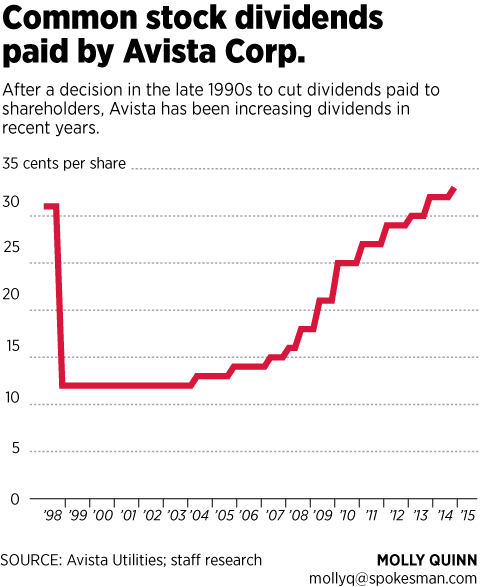

Shareholders expect to get their money back, with profits, through two channels: Avista’s stock increasing in value over time and dividends, Norwood said. After cutting dividends sharply in the late 1990s, the utility’s board of directors has voted repeatedly to increase them over the past decade. (See dividends chart.)

Avista pays out 60 to 70 percent of its earnings as dividends, which is comparable to other utilities, Norwood said.

Return on equity, or profit

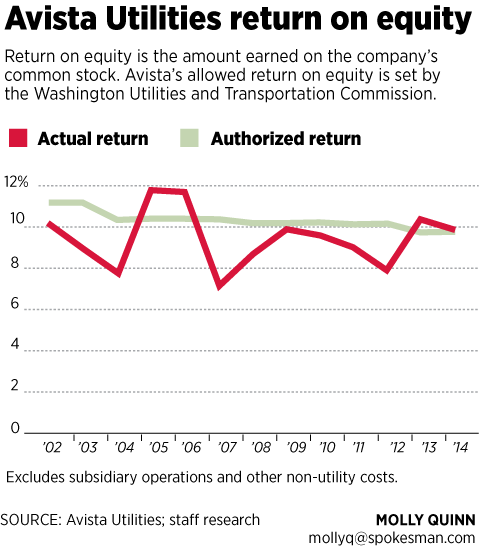

In rate cases, public utility commissions set the “return on equity” for each utility. It’s the return Avista can earn by investing in the infrastructure that serves electric and natural gas customers.

“You can think of it as their profit,” said Lisa Gafken, an attorney for the Office of Public Counsel. “Return on equity is a completely geeky topic, but it’s the big issue that drives most rate cases.”

Commissions are charged with setting rates so companies can recover their investment costs and earn a reasonable return.

Gafken said her office typically brings in experts to testify on consumers’ behalf on rate-of-return issues.

“They do a pretty in-depth analysis,” she said. “They look at the industry and comparable companies, determining what investors are demanding in terms of their return.”

In recent years, the Office of Public Counsel has argued for lower return on equity, noting that the cost of borrowing money has dropped. (See return on equity graph.) In the current Washington rate case, Avista is asking for a 9.9 percent return on equity.

The utility doesn’t always earn the allowed return rate, Norwood noted. During mild winters, for instance, Avista sells less energy, which cuts into the company’s profits. In other years, the utility earns more than the allowed return.

Different states have different mechanisms for determining how that money gets refunded to customers. It can appear as a rebate on future bills.

Executive pay

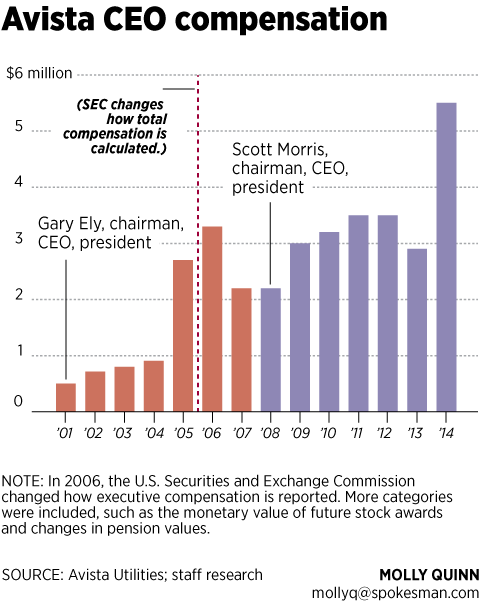

Morris, Avista’s chairman and CEO, earned nearly $5.5 million in total compensation last year. Not all of that was take-home pay.

In addition to Morris’ salary and performance bonuses, his compensation package included the value of future stock awards and a net gain in the value of his pension.

Morris’ pay makes headlines every year, but only about $550,000 of his compensation package gets included in customers’ rates, Norwood said. The rest is paid by shareholders and comes out of company profits.

“I wouldn’t argue with anyone that ($5.5 million) is a big number,” Norwood said. “Customers say, ‘I shouldn’t pay for that,’ and they aren’t.”

For the past two years, Avista’s shareholders have endorsed the compensation paid to the company’s top executives through a “Say on Pay” advisory ballot, Norwood said. More than 90 percent of those voting said the amount was appropriate.

“He’s being paid at a level comparable to other utility CEOs,” Norwood said.

But Morris’ pay still raises eyebrows in Spokane.

“Keep the spread between blue-collar workers and executives a little lower,” Plastino, the neighborhood association president, told Norwood at the meeting.

What Avista is doing to cut costs

Avista has been working to contain its payroll and employee benefit costs, which were rising rapidly, Norwood said.

The company offered buyouts in 2012 to reduce its workforce, resulting in $5 million in annual savings. Hiring restrictions remain in effect. Filling a vacant position, or creating a new one, requires authorization from Morris, Avista’s human resources director and the company’s chief financial officer, Norwood said.

Avista also has changed retirement plans for new, non-union workers. Instead of a traditional pension plan, the workers are eligible for a 401(k) match. The company also is transitioning out of paying for medical coverage for retirees.

What’s next with rates?

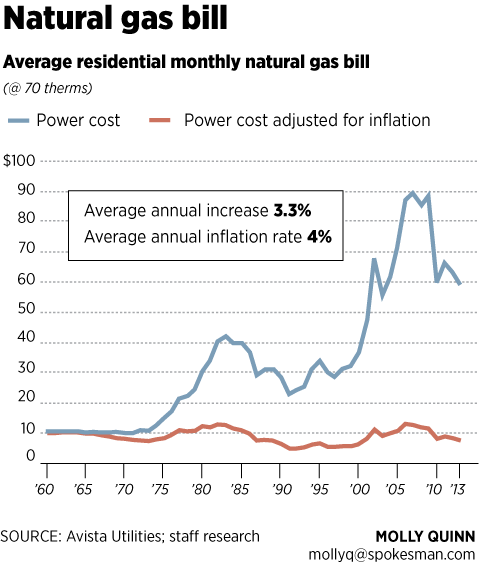

Avista’s current rate case is pending before the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission. The utility is asking for a 6.7 percent increase in electricity rates and a 6.9 percent rate increase in natural gas rates, effective Jan. 1. If granted, the rate hike would generate an additional $45 million annually for Avista.

The commission is accepting written comments on the proposal, and a public hearing in Spokane will be scheduled for fall.

Meanwhile, the commission will meet in April to begin a longer-term discussion of how Avista recovers capital spending costs.

Company officials say there’s too much of a lag between when they spend money on big capital projects, and when they get to recover those costs through higher rates. That has led to periods when Avista earned less than the state-authorized return on equity, Norwood said.

“When your costs are growing faster than your revenues, you’re going to have a shortage,” he said.

During Avista’s last rate settlement, the parties agreed to discuss the issue of regulatory lag and how it affects company earnings.

In Idaho and Oregon, regulators allow the company to include some forward-looking costs in rates, based on spending projections, Norwood said. In Washington, rates are set on current costs, with a few exceptions. Future raises outlined in union contracts, for instance, can be included in rates.

From a state regulator’s viewpoint, the lag in cost recovery isn’t always a bad thing, Kermode said. It helps mimic a competitive environment, encouraging utilities to reduce their costs and work more efficiently, he said. The Office of Public Counsel also has concerns about including costs in rates based on future budget projections versus actual costs, Gafken said.

“It’s based on things that are very squishy and likely to be inaccurate,” she said.

In Washington, Avista and other utilities are filing rate cases every year, or nearly every year, she noted. “We question whether they really need this special tool.”