He followed his dad into firefighting, and stuck with it through tragedy

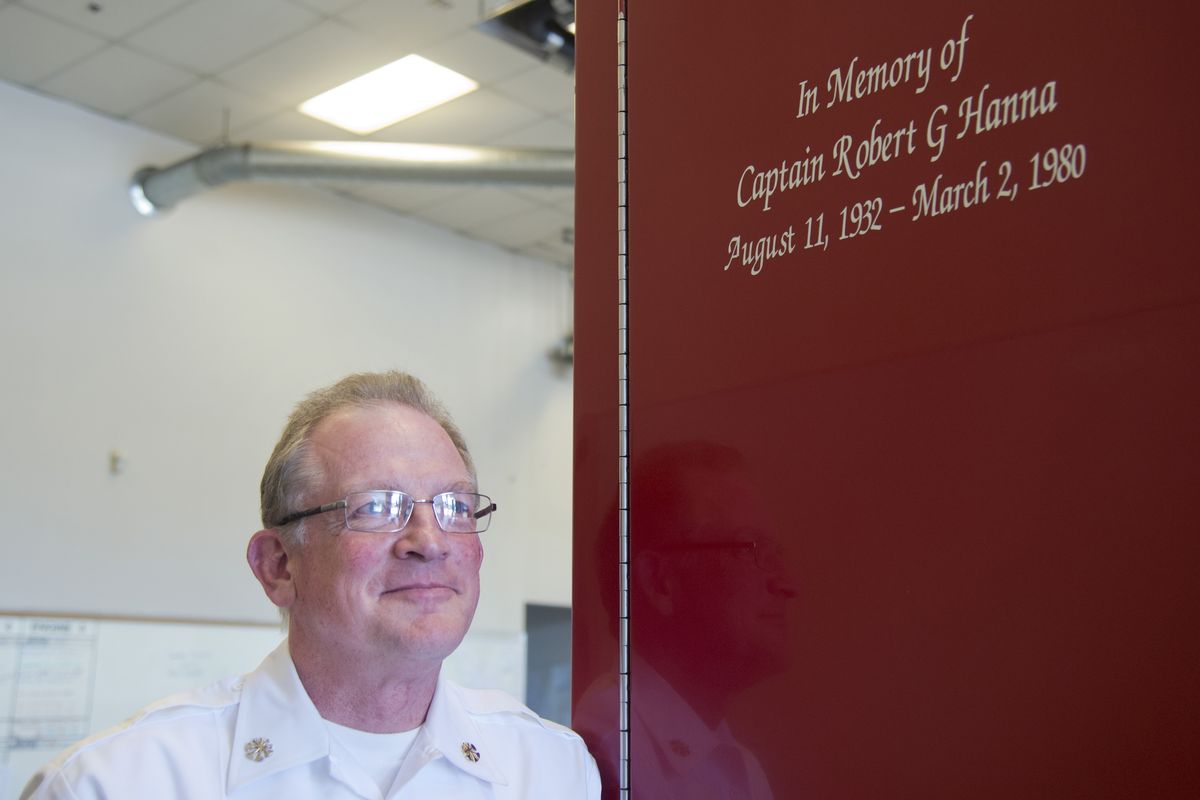

Retiring Spokane Deputy Fire Chief Robert Hanna stands next to a ladder truck bearing a memorial to his father, who died on duty 35 years ago. (Jesse Tinsley)Buy a print of this photo

Ever since the day a falling piece of the burning Zukor Building struck and killed Spokane Fire Capt. Bobby Gene Hanna, his son Robert Hanna has tried to fulfill his father’s legacy.

The younger Hanna raised a family and now dotes on his grandchildren, knowing that his own father never got to meet his first grandchild. He also spent a long career in his father’s profession, firefighting, with an emphasis on training and safety.

On June 30, Hanna, 58, a deputy fire chief, will retire after more than 35 years on the job.

If any one thing guides Hanna, it’s his father.

“I emulate my dad,” Hanna said.

The younger Hanna was a rookie on Engine No. 6 when he was sent to the Zukor Building fire on March 2, 1980, as part of the morning relief crews. The fire had subsided to smoldering ruins. Just as he arrived, his father was being loaded into an ambulance. A half-hour later, Capt. Hanna was pronounced dead.

“I saw him briefly after they loaded him into the ambulance,” Hanna said.

The Zukor Building fire is an unsolved arson. Because it led to the death of a firefighter, it’s also considered a homicide.

Capt. Hanna, 47, was one of two men in the Station No. 7 ladder bucket, which was extended to the midpoint of the six-story historic Zukor Building at the corner of Riverside and Wall, where the STA Plaza now sits.

Retired firefighter Bob Green was beside him.

The two were positioned about 15 feet from the north side of the masonry building when a large section of the north wall gave way.

Green, who retired as a battalion chief six months ago, said he still feels the pain of the loss.

He recalled that the roof above the sixth floor was completely gone and he wondered to himself, “What is holding this thing together?”

Green was manning the master stream nozzle in the bucket when Hanna, a 22-year veteran, took it to give him a break.

“We heard a terrible cracking noise. We both looked up and saw it coming at us,” Green said. “I braced for the worst.”

Green said that as pieces of the upper story came toward him, he thought he was going to die.

Out of the corner of his eye, he said, he saw a piece of the upper cornice strike Hanna. “He went down and did not move,” Green said.

In the split second between life and death, Green turned away from the collapsing wall and was knocked out of the bucket by the debris. He tumbled down a few rungs of the ladder and clung there until rescuers got to him.

Hanna was pronounced dead at Sacred Heart Medical Center.

Green suffered two broken ribs and a back injury.

“To this day, I don’t know why it was Bob instead of me,” Green said.

“He was an excellent fireman. He had a great sense of humor. I looked up to him,” said Green, who also followed his father, Bob Green, into the Spokane Fire Department.

Plaque dedicated in memory

On March 2 – 35 years to the day after Hanna was killed – his son, Green and dozens of firefighters from around the region gathered where the Zukor Building once stood. They dedicated a plaque in memory of Capt. Hanna, the 15th Spokane firefighter killed in the line of duty.

The plaque is embedded in the sidewalk outside the northwest corner of the STA Plaza. It’s one of 17 such memorials placed around the city in locations where firefighters were killed, an effort spearheaded by Spokane firefighter union Local 29 and Lt. Greg Borg.

The plaque said the blaze was the only four-alarm fire in Spokane between 1950 and 1980.

A natural athlete

Capt. Hanna grew up in McKinney, Texas, the son of a tire dealer. He served as a bombardier in the Air Force in the early 1950s and was stationed at Fairchild Air Force Base where he met his wife, Carolyn.

His name, Bobby Gene, reflects his Texas heritage. He had three sons; Robert was the oldest.

A natural athlete, the elder Hanna played on the first fire department baseball team and was a skilled golfer.

“I still have his golf clubs,” the younger Hanna said.

His dad had a reputation as a “quiet prankster.”

“Everybody called him Bob. He fit right in,” Hanna said.

In addition to holding down shifts as a firefighter, the elder Hanna hauled bulk concrete to Spokane from Metaline Falls, Washington, and worked for a natural gas company.

He got Robert Hanna a job hand-digging gas lines at age 15.

“He took us on camping trips. He taught us to play baseball. He taught me how to play golf and football,” Hanna said.

So it was natural for the son to follow his father into the fire department.

Enjoying his grandchildren

Now with grandchildren of his own, Hanna still regrets that his father never met his grandchildren.

Bobby Hanna’s first grandchild, Robert Hanna’s daughter, was born 12 days after his death. Today, Elysia Hanna Spencer works at WSU Spokane. Her husband, Whitman Spencer, is a firefighter for Spokane County Fire District 9.

Hanna’s son is Army 1st Sgt. Shawn Hanna, a Purple Heart recipient from one of two tours in Afghanistan. He has a partial disability from a gunshot wound to his lower right leg.

One of Hanna’s greatest pleasures, he said, is visiting his children, their spouses and his four grandchildren.

Hanna’s own home near Wandermere is equipped with bunk beds for visits by the grandkids.

Like his dad, Hanna has been dedicated to his kids, learning soccer and becoming a coach for his kids’ teams in their early playing years. His son went on to compete at Riverside High School and Whitworth University. Today, Hanna is a faithful soccer grandpa, attending the children’s soccer games.

After his father died, Hanna said he started looking to older firefighters for mentoring. “You always look to somebody for advice at some point,” he said. He found plenty of help among his colleagues.

Training, safety paramount

Hanna was promoted to lieutenant in 1990 and served as a training instructor from 1997 to 1999. He became a captain in 2000, serving as a department arson investigator. In 2005, he was promoted to battalion chief for training. Four years later, he was appointed deputy chief.

Things have changed dramatically since his dad died, he said. Fires tend to burn hotter and are more toxic, because of the plastics in modern buildings. Firefighters are better trained and better equipped. But they also spend more time on medical calls than they do fires; today, about 80 percent of the department’s 33,000 annual calls are for medical emergencies.

The emphasis on training and equipment comes with a deeper purpose for Hanna.

“We don’t ever want to see a line-of-duty death,” he said. “We don’t want to have to make that phone call.”

‘A murder case’

Assistant Fire Chief Brian Schaeffer reached into a standard-size cardboard box recently and pulled out a stack of photographs and other materials that comprise the investigative record into the Zukor Building arson.

“That box represents a murder case,” Schaeffer said.

The Zukor Building was originally named after pioneer E.H. Jamieson, who built the structure in 1890.

Zukor’s Inc., a successful chain of stores of fine women’s apparel, moved into the building in 1935. Two years later, the Zukor family bought it.

The building was sold in 1972 to Lee Solomon, owner of Mandell’s Credit Jewelers.

At the time of the fire, the upper floors of the Zukor Building as well as parts of adjacent buildings were mostly vacant. The ground floor held B. Dalton Booksellers and Hal’s Stereo.

Investigators at the time acknowledged that there had been a series of break-ins and fires in that part of downtown, and that security in the Zukor Building was weak. Fires in the nearby Peyton and Kuhn buildings were quelled in 1979. The Kuhn Building fire was ruled arson. The two-alarm fire in the Peyton Building was ruled suspicious, according to news files.

The investigation pointed to the possibility that the fire was started by a transient, officials said.

At the time, Solomon, the building owner, said he believed that the arsonist broke into the building from a fire escape off the alley on the south side of the building. The fire was started on the second floor.

He stuck with firefighting

After his father’s death, Robert Hanna could have quit for a safer job. “He could have walked away and done anything else,” Schaeffer said.

Hanna acknowledged that the loss of his father set him back for a time.

“I thought about quitting,” he said, “but I wanted to be like him … I’m sure he’d be proud of my career.”