Landowners face uncertainty as north-south freeway gets boost in funding

Where Freya Street curves to meet Greene Street on its way north, the future North Spokane Corridor will cut through the industrial neighborhood to the west, using land currently occupied by several longstanding heavy equipment businesses. (Jesse Tinsley)Buy a print of this photo

Stacey Jordan has been waiting two decades for an answer to when the state will take the property that holds his family-owned business. Industrial Welding, at 1203 N. Greene St., specializes in heavy equipment construction and repair and is in the path of the North Spokane Corridor.

With the Legislature voting recently to increase the gasoline tax and spend $11 billion over the next 14 years on new transportation projects, he will get an answer. Included in that new spending is nearly $879 million to engineer, buy up real estate and build the southern portion of the corridor, also known as the north-south freeway.

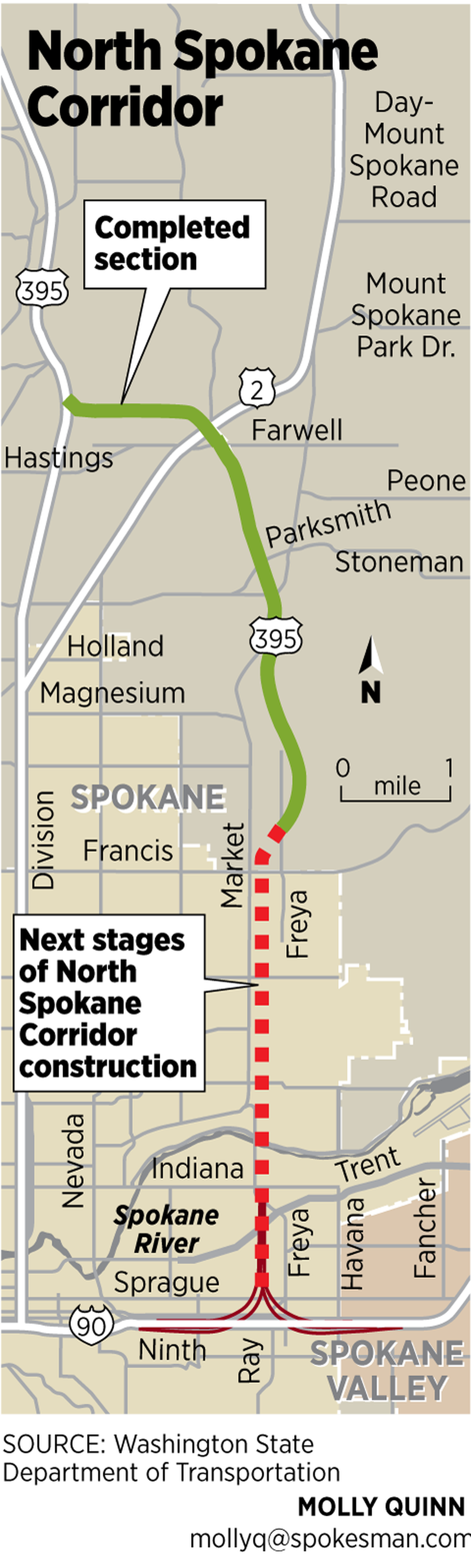

More than 5 miles of the corridor is complete on the north end of the route – from Wandermere to Freya Street near Hillyard. Work is underway to prepare the path through the industrial area of Hillyard, including rerouting rail lines so the new roadway can continue southward.

Plans call for building an elevated corridor from the north bank of the Spokane River southward along the west parking lot of Spokane Community College and across the heavy industry that lines railroad tracks to the south. But questions remain about property acquisitions closer to Trent Avenue and Interstate 90.

Jordan’s business is in the middle of the mix.

“I am waiting for them,” Jordan said last week after learning that lawmakers have come up with money to finish the freeway.

“It’s been at least 20 years since the north-south freeway was supposed to be going through,” said his wife, Ronda Jordan.

A long time coming

When campaigning in Spokane for U.S. Senate in 1983 and governor in 1992, Democrat Mike Lowry often got a chuckle by recalling his father’s yardstick for when anyone claimed something was really old.

“He’d say, ‘That’s so old it was before they talked about the north-south freeway,’ ” said Lowry, a native of St. John in Whitman County. “He realized everybody would realize it was a long time ago.”

The long-discussed roadway to pull some north-south traffic off Division Street was controversial from its inception, in large part because it would displace homes and businesses. One early proposed route went through the Lidgerwood and Logan neighborhoods on the Nevada-Hamilton arterial. The massive Hamilton Street exit on Interstate 90 was planned to become the start of the freeway. But north Spokane politicians made their bones by fighting to keep those neighborhoods from being split the way Interstate 90 split East Central, and that route was abandoned.

State Rep. Timm Ormsby, D-Spokane, remembers being in St. Aloysius Elementary School in the 1960s when his class got a visit from Rep. Margaret Hurley, then a senior Democratic member of Spokane’s legislative delegation. “She was just death on it,” he recalled.

Democrats in the Legislature from central Spokane were wary of a road that would tear up neighborhoods. Republicans from districts outside the route were opposed to the taxes needed to pay for it. City and county officials argued over it for decades. Business organizations wanted it to move goods more efficiently in or around Spokane. Environmental groups questioned the cost and the need.

The route near Hamilton formally was abandoned by the state in 1991, and planning for the corridor shifted east to the current route. But controversy remained.

The first significant state money for the freeway wasn’t promised until 2003, when the project was among those to get money from a new 5 cent increase in the gasoline tax. The project, which by then had achieved mythical status, got money for design, land purchases and construction of the first leg. At least $125 million promised from the nickel gas tax has grown to about $274 million so far, according to the state Legislative Evaluation & Accountability Program Committee.

Two years later, when legislative leaders proposed an additional 9.5 cent bump in the gas tax, the corridor was included in a package of transportation “mega-projects” to sell legislators around the state. That package was put together so quickly the Chamber of Commerce and Associated General Contractors, two big proponents of the proposed freeway, didn’t get enough advance notice to put on a lobbying blitz, recalled Ormsby, who by then was a freshman House member from Hurley’s old district.

The Spokane road project was offered $152 million from the new tax revenues, he said. Raising the gas tax is never popular, and that increase initially failed, with most of the Spokane delegation voting no. House leaders began looking for votes to pass it on a second go-round.

Some delegations drove hard bargains, Ormsby recalled, and projects in their counties gained significantly by the time the votes were corralled to pass that gas tax increase. Most Spokane members held firm to their no votes. The north-south freeway allocation from that jump in the gas tax hardly moved.

“Projects follow people’s willingness to come up with the money,” Ormsby said last week.

Since 2003, the project has collected money from a variety of state and federal sources. When all the money spent on engineering, right of way purchases and construction is toted up, the corridor has consumed about $726 million so far, based on state figures.

Waiting on the state

The Jordans are like others in the path of the corridor: The long-sought project has put a cloud over their futures. With so much uncertainty over the property, potential buyers wouldn’t be interested, they said, and the state has not had money to buy them out – until now.

Industrial Welding was started by Stacey Jordan’s father, Chuck Jordan, and a partner in 1970. Stacey Jordan said he’s more than willing to sell his property and relocate, but he needs enough money to do it.

The land alone is worth upward of $1 million, he estimates, and the cost of moving could be equal to that. Finding the right land in a good location won’t be easy, and moving his cranes and lathes and presses is another hurdle.

If he has to shut down for a significant time for the move, Jordan might lose his workforce of six skilled welders and machinists. And customers may not be able to find someone to do the specialty work he offers.

Jordan said his best option would be for the state to buy him out and lease back the property so he would have time to relocate.

Just up the street, Teri Dawley, at Sweet Old Bob’s restaurant and bar, said she and her father, Bob Nordby, have been waiting just as long.

“It’s been a hardship because they wanted to retire and couldn’t sell it,” she said.

State officials have told the family that their property is needed for a southbound offramp at Trent Avenue. With a cloud over the future of the property, no one is interested in buying the restaurant or its 31,000-square-foot parcel.

Calls to state transportation officials have been less than helpful, Dawley said.

“They always play dumb when you call,” she said, explaining that they have provided her and her father with no information about when their land would be purchased. But she was told that because their property is in an area with numerous engineering issues, it would likely be the last to see construction.

Completion date unknown

Until recently, local and state officials quoted the cost to complete the corridor as $750 million, but that was based on a 2012 estimate that assumed all the work was completed at that year’s prices. The new figure of $879 million reflects inflation as the project is spread out and finished around 2030.

The state has mapped out 16 years of projects on which to use the money from the gasoline taxes that will go up 7 cents on Aug. 1 and another 4.9 cents next July 1. But the Legislature approves the spending two years at a time, and amounts can be shifted around in future sessions.

Although the North Spokane Corridor is allocated specific amounts for engineering, right of way purchases and construction in each of the next six bienniums, state officials stress that those figures are estimates and a firm construction plan to connect to I-90 has not been set. Generally speaking, construction will continue from north to south, but some interchanges may take longer to finish and unexpected engineering challenges could force changes in the design, said Lars Erickson, the department’s chief spokesman.

If it is finished sometime in the 2029-31 budget cycle, that will be more than a quarter-century after the first money was approved in 2003, and almost three-quarters of a century after talk of a north-south freeway began to roil local politics.

“That would be an accomplishment, to be there when they finish it,” Lowry said last week. “I’m 76. I’d be lucky to still be here, but I would like to live long enough to see the completion.”