Omar Sharif, of “Doctor Zhivago,” “Lawrence of Arabia,” dies

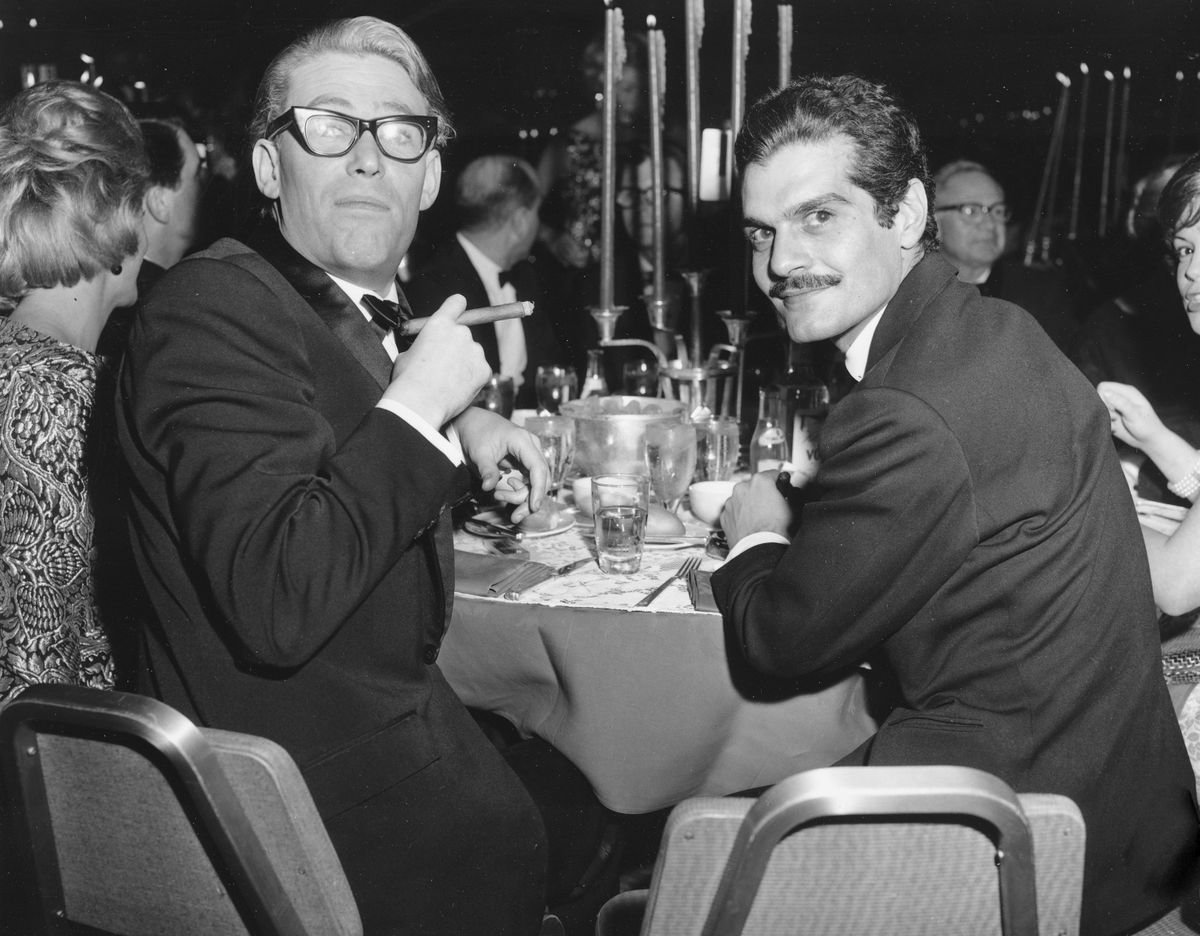

Peter O'Toole (right) as T.E. Lawrence, with co-star Omar Sharif, from the 1962 film "Lawrence of Arabia." (Associated Press)

CAIRO (AP) — Omar Sharif, the Egyptian-born actor with the dark, soulful eyes who soared to international stardom in movie epics, “Lawrence of Arabia” and “Doctor Zhivago,” died Friday. He was 83.

Sharif died of a heart attack in a Cairo hospital, his longtime agent, London-based Steve Kenis, and the head of Egypt’s Theatrical Arts Guild, Ashraf Zaki, told The Associated Press. The actor had been suffering from Alzheimer’s.

Sharif was Egypt’s biggest box-office star when director David Lean cast him in 1962’s “Lawrence of Arabia.” But he was not the director’s first choice to play Sherif Ali, the tribal leader with whom the enigmatic T.E. Lawrence teams up to help lead the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

Lean had hired another actor but dropped him because his eyes weren’t the right color. The film’s producer, Sam Spiegel, went to Cairo to search for a replacement and found Sharif. After passing a screen test that proved he was fluent in English, he got the job.

His entrance in the movie was stunning. He was first seen in the distance, a speck in the swirling desert sand. As he drew closer, he emerged first as a black figure on a galloping camel, slowly transforming into a handsome, dark-eyed figure with a gap-tooth smile.

The film brought him a supporting-actor Oscar nomination and international stardom.

Three years later, Sharif demonstrated his versatility, playing the leading role of a doctor-poet who endures decades of Russian history, including World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution, surviving on his art and his love for his beloved Lara in “Dr. Zhivago.”

Lean’s adaptation of the Boris Pasternak novel had a rocky beginning in its first U.S. release. Attendance was sparse and reviews were negative.

After MGM removed it from theaters and Lean re-edited the sprawling tale, it was re-released and became a box-office hit. Still, Sharif never thought it was as good as it could have been.

“It’s sentimental. Too much of that music,” he once said, referring to Maurice Jarre’s luscious Oscar-winning score.

Although Sharif never achieved that level of success again, he remained a sought-after actor for many years, partly because of his proficiency at playing different nationalities.

He was Argentine-born revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara in “Che!”, Italian Marco Polo in “Marco the Magnificent” and Mongol leader Genghis Khan in “Genghis Khan.” He was a German officer in “The Night of the Generals,” an Austrian prince in “Mayerling” and a Mexican outlaw in “Mackenna’s Gold.”

He was also the Jewish gambler Nick Arnstein opposite Barbra Streisand’s Fanny Brice in “Funny Girl.” The 1968 film was banned in his native Egypt because he was cast as a Jew.

In his middle years Sharif began appearing in such films as “The Pink Panther Strikes Again,” ”Oh Heavenly Dog!,” ”The Baltimore Bullet” and others he dismissed as “rubbish.”

The drought lasted so long that finally, beginning in the late 1990s, Sharif began declining all film offers.

“I lost my self-respect and dignity,” he told a reporter in 2004. “Even my grandchildren were making fun of me. ‘Grandpa, that was really bad. And this one? It’s worse.’”

In 2003 he accepted a role in the French film “Monsieur Ibrahim,” portraying a Muslim shopkeeper in Paris who adopts a Jewish boy.

The role won him the Cesar, the French equivalent of the Oscar, and he followed with “Hidalgo,” a lively western starring Viggo Mortensen. In that one he was a desert sheik who duels 11 assailants with a sword. His career was back on track.

He suffered a public embarrassment in 2007, however, when he pleaded no contest to misdemeanor battery and was ordered to take an anger management course for punching a parking valet who refused to accept his European currency.

Born Michael Shalhoub in Egypt’s Mediterranean coastal city of Alexandria, Sharif was the son of Christian Syrian-Lebanese parents.

After working three years at his father’s lumber company, he fulfilled his longtime ambition to become a movie actor, going on to appear in nearly two dozen Egyptian films under the name Omar el Sharif.

His fame only increased when he married Egypt’s then-reining movie queen and screen beauty, Faten Hamama, in 1955. Some of Egypt’s most iconic film posters are of Hamama and Sharif. Sharif converted to Islam to marry her, and they had a son, Tarek. Hamama died in January.

They divorced in 1974, and Sharif never remarried.

“He was a phenomena; a one of a kind. Everyone had a dream to be like Omar Sharif. No one will be like him,” Yousra, Egypt’s biggest actress for much of the past 30 years and a close friend of Sharif, told the AP on Friday after his death was announced.

“I don’t think we are going to ever have someone like him,” she said, describing him as “classy” and comparing him to a diamond that is “clean-cut.”

Sharif’s son Tarek revealed in May that his father had been suffering Alzheimer’s. Zaki, the Egyptian Theatrical Arts Guild president, told the AP Friday that Sharif had stopped eating and drinking in the last three days.

Sharif was romantically linked with a number of Hollywood co-stars over the years. In 2004, he acknowledged that he also had another son, who was born after a one-night stand with an interviewer.

Away from the movies, Sharif was a world-class bridge player who for many years wrote a newspaper column on bridge. He quit the game in later years, however, when he gave up gambling.

He had been a prodigious gambler, reportedly once winning a million dollars at an Italian casino. After losing a substantial amount at a Paris casino in 2003, he insulted a croupier and was ordered to leave. When he refused, he was thrown out and head-butted a policeman during an ensuing scuffle. He was fined $1,700 and given a one-month suspended sentence.

Sharif spent much of his later years in Cairo and at the Royal Moncean Hotel in Paris.

“When you live alone and you’re not young, it’s good to live in a hotel,” he told a reporter in 2005. “If you feel lonely, you can go down to the bar. I know all the people who work here and who come here regularly. The room is done for you, and you don’t have to worry about anything,” he said. “If you feel anything, health-wise, you can call the concierge and tell them to bring all the ambulances in Paris.”

___

Katz reported from London. Biographical material in this story was written by The Associated Press’ late Hollywood correspondent, Bob Thomas. National Writer Hillel Italie in New York contributed to this report.