In windstorm aftermath, arborists suggest evaluations before removing more trees

Tree climber Sean Price of Northwest Plant Health Care cuts the larger tree trunks to length so they can be sold as timber in Patrick Byrne Park in North Spokane, Wednesday, Dec. 2. 2015. Byrne Park was one of the hardest hit by the Nov. 17, windstorm. (Jesse Tinsley / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

As students started their journey home on Nov. 17, a towering pine collapsed on a parked car just outside Jefferson Elementary School.

Teachers and school leaders hurried children back inside as the winds blew stronger.

About the same time, at Franklin Elementary, as some students started their walk home, a pine toppled across 17th Avenue a few blocks from the school.

At Whitworth University, the campus arborist remained in his office though classes were canceled. More than 130 trees fell or were so damaged they had to be removed.

“I was scared for the students and the faculty,” said Will Mellott, Whitworth’s campus arborist.

All over the Inland Northwest, there were close calls from falling trees. Cars smashed moments after drivers had parked. Roofs crushed as residents huddled beneath them.

And tragedies were not avoided. A woman died in her South Hill yard when she was struck by part of a pine that snapped. A driver was killed when her car was struck near Cheney. A man near Twin Lakes, Idaho, was paralyzed when a tree hit his truck.

It was the worst windstorm recorded in Spokane, according to the National Weather Service. But it happened not much more than a year after a strong thunderstorm also hobbled the region when falling trees cut power and caused significant damage. And that storm was less than two weeks before another storm that did the same.

The ferocity of the November storm and proximity to two other significant wind events has some homeowners with trees left standing worried about the next strong gust.

“We’re already getting calls like that from people saying, ‘When you’re done, please remove the other eight trees in my yard,’” said Joe Zubaly, president of Northwest Plant Health Care Inc., a tree care and landscape company. “I can’t blame people for that.”

But tree experts urge caution, even if they say the storm reawakened them to the possibility of healthy tree failures.

“I was shocked at the amount of damage this storm did,” said David Kozora, owner of Arborworks, a local tree service. But he added, “I try to stay away from the hysteria.”

Nearly all the trees pushed down by the wind were conifers.

“The only deciduous trees I’ve seen lost were ones hit by another falling tree,” said Angel Spell, the city of Spokane’s urban forester.

One reason for that, experts say, is simple: Leaves already had fallen.

“The amount of material for the wind to get ahold of is greatly reduced” when leaves fall off. A conifer, however, is like “a sailboat with all the sails up,” Kozora said.

Among the conifers, spruce trees appeared to fare worst, several arborists said.

But the species with the most failures was ponderosa pine. That’s in large part because it’s the most prevalent species in the Inland Northwest. But other factors, arborists say, may have played a role.

Irrigated places

hit hard

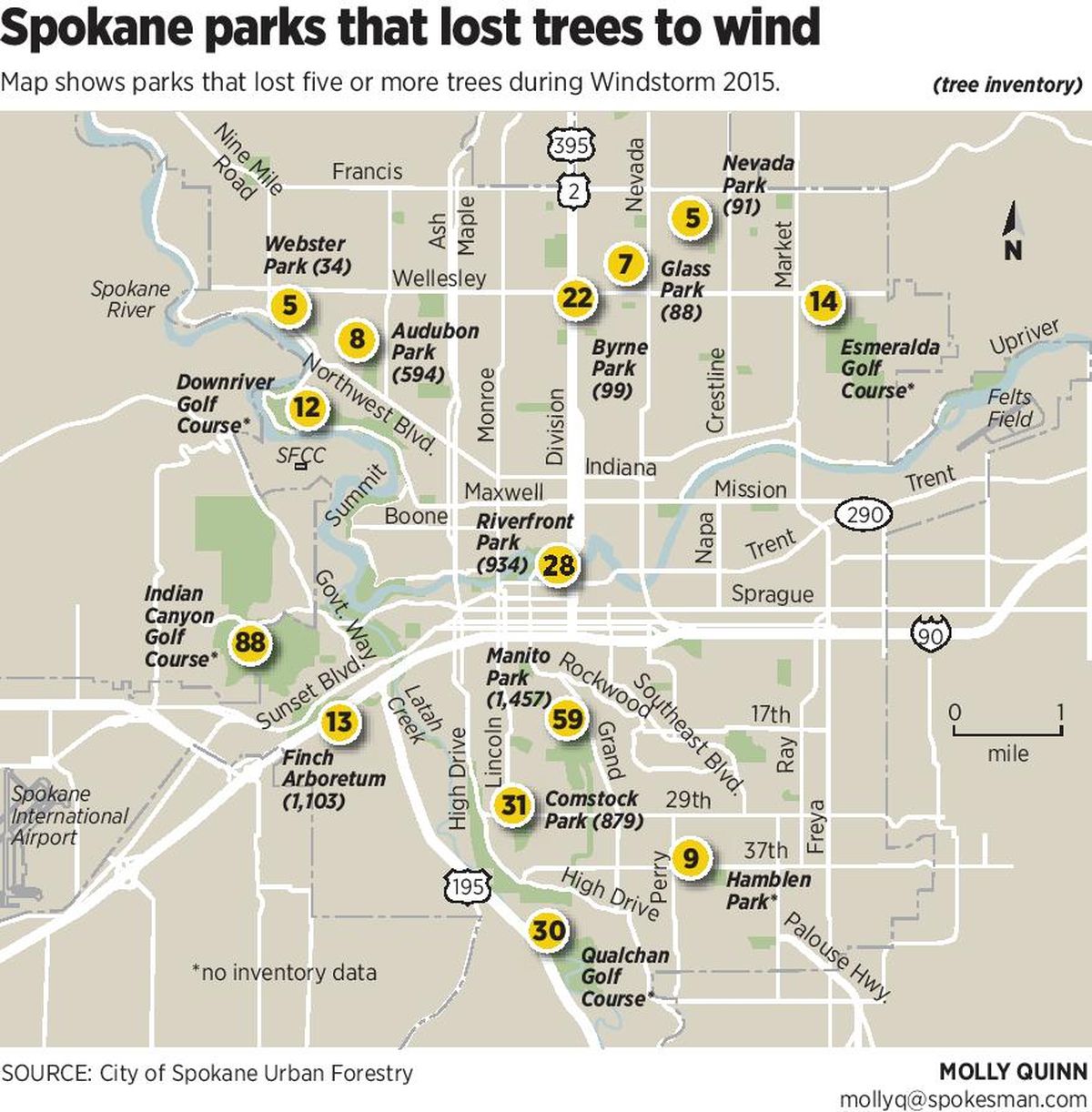

Parks, golf courses and cemeteries were hit particularly hard in the storm.

Some Spokane city parks lost a significant portion of their pines. At Webster Park, a small park in northwest Spokane, six of the 10 tall pines uprooted. At Byrne Park, not far from NorthTown Mall, 22 fell, about a third of the pines there.

Irrigated historic cemeteries lost dozens of trees, as did Indian Canyon Golf Course.

“The significance is in how many huge, mature ponderosas were lost and the value of the mature trees,” Spell said.

A mature ponderosa pine often has a value of more than $10,000 for insurance purposes. But the loss is more than monetary, she said. The trees capture rain, preventing it from heading into the city’s crowded sewer system. They provide shade that helps lower energy costs to homes.

Some arborists suggest there could be a reason for devastation of irrigated areas.

Ponderosa pines, which are native and accustomed to the dry climate, usually anchor a deep tap root in search of water. An irrigated pine, they suggest, may keep its roots closer to the surface.

“When people water their lawns the trees get lazy,” said Steve McConnell, regional extension specialist in forestry, for Spokane County extension. “The result is the tap root isn’t developed as they are in a natural setting.”

But Eric Turnblom, associate professor of forest resources at the University of Washington, said irrigation is unlikely to discourage deep development of roots in pines.

“The research there seems to indicate that if it has a rooting habit to send down a tap root, it still will,” he said.

Bernard Bormann, University of Washington forest ecology and physiology professor, agreed.

“It has a natural proclivity to send that tap root down,” he said. “My guess is that, yes, the tap root will grow, probably regardless of the irrigation on the top.”

Zubaly said another factor could be that irrigation promotes growth of branches.

“Ponderosa pines in irrigated and fertilized areas also will put on a larger crown, which means a higher wind sail,” Zubaly said.

Bormann said while irrigated trees may be more stout, the bigger branches produce more sugar, which the trees will use, in part, to make a more robust root system that should help make it more stable.

Turnblom doesn’t dismiss that damage could have been worse in irrigated areas.

“There still could be other differences between the non-irrigated and irrigated sites at work here,” he said.

While arborists noticed high failure in irrigated areas, many trees also fell in natural areas.

Eighty-two trees fell on the road to Mount Spokane State Park. More than 1,000 fell over Nordic, snowshoeing and other trails in the park, said Mt. Spokane Ski and Snowboard Park Manager Steve Christensen.

Christensen said a majority of the trees that fell were lodgepole pines. But grand firs and Douglas firs also were hit hard.

Destruction

sparks questions

Devastation from the storm surprised many arborists.

McConnell took note of trees that fell at a nearby school and wondered if the recent storms should change anything about how arborists maintain the urban forest.

Among possible questions to consider: If spruces experienced a poor failure rate, are there places – especially near where people congregate – where they should not be planted? Are there lessons to be learned from the ponderosa pines that toppled? Should irrigation schedules be reconsidered? Is it possible that climate change is making stronger wind more likely in the Inland Northwest?

“A lot of people are thinking that what happened is part of the new normal and not just a 100-year event,” said Garth Davis, forestry program manager for the Spokane Conservation District.

McConnell is organizing a committee of experts to review the storm to consider making recommendations.

Spokane’s urban forestry department will participate in the review, Spell said.

“Once we get through the cleanup and look at the details of the failures, we’ll start to look at how can we approach this better,” she said.

It’s the wind, duh

Numerous factors play into a tree’s failure. Rocky soil that blocks root development is one. Disease that weakens a tree is another. So is a tree’s height.

Much is basic physics.

“The taller the tree, the more leverage,” Bormann said. “It’s like a prybar.”

Bormann said there are models that examine how much wind it takes to blow over trees, but determining that in most settings is extraordinarily difficult.

“The cause was the intensity and the duration of the wind,” said Mellott, Whitworth’s campus arborist. “You basically had hurricane force winds blowing for like nine hours.”

Spokane International Airport measured a gust of 71 mph at the height of the storm. Hurricane force is 75 mph.

“Once it gets up that high, healthy trees fail,” Davis said.

The 71 mph reading was the second highest recorded in Spokane. The highest reading, 77 mph, was during a thunderstorm about 10 years ago. Perhaps more problematic, sustained winds more than 40 mph lasted for several hours.

“The biggest component to this was the high winds,” Davis said.

Keeping calm

Many tree experts suggest that homeowners have their taller trees assessed by an expert.

The conservation district will inspect trees for no fee to advise residents on trees they’re concerned about, Davis said.

“I am concerned about an overreaction,” Spell said. “It’s important for people to have their trees assessed.”

Zubaly said he noticed that many trees that snapped broke a bit above or below a deformity in the trunk. Ponderosa pines with two tops also didn’t fare as well.

Many problems can be dealt with by pruning, Zubaly said. Trees with double tops can be cabled so they move together in the wind.

“Our company is into tree preservation,” Zubaly said. “We don’t believe that any tree within reach of the home is a hazard.”

Lawrence B. Stone, president of the ponderosa pine advocacy group Spokane Ponderosa, stressed that the number of ponderosas that fell was tiny compared to the number that still stand. He also noted that many non-native species, like spruce, fared worse.

“Spokane Ponderosa recommends property owners confer with a certified arborist prior to making any decision on removal of trees,” Stone said in an email. “Our Ponderosa Pine urban forest is an important part of the value of properties and large-scale tree removal from a property often results in reduced property value on resale.”

Bormann urged caution in cutting trees, noting not only their aesthetic value but importance for creating habitat and helping shade people’s homes.

He cautioned, however, that trees near where other trees failed will be exposed to different wind patterns. As a rule of thumb, he said, it takes a tree about five years to grow roots to adjust. Trees in open areas for many years usually are well-adapted to the wind. On the other hand, storms that blow in from unusual directions can cause more failures because trees aren’t prepared.

“If this is the worst windstorm that we’ve experienced ever in the history of Spokane and your tree is still standing, then the strong survived,” Zubaly said. “That may be a way of reining in the craziness.”