This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

The Slice: Long road to recovery

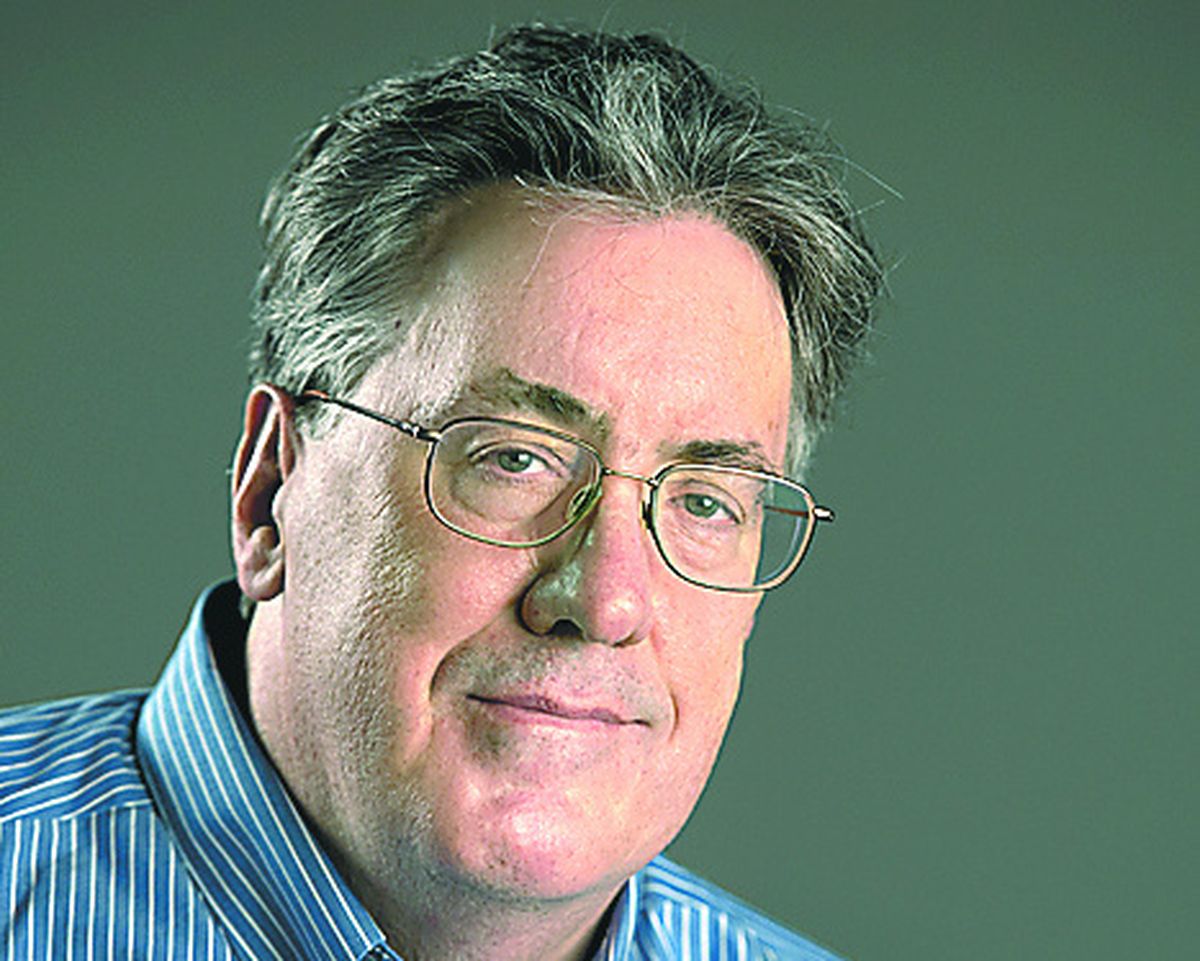

Paul Turner, Spokesman-Review columnist, sits at home Aug. 3 as he recovers from a rare brain infection that sidelined him for six weeks. (Jesse Tinsley)Buy a print of this photo

Editor’s note: The Slice columnist Paul Turner has been on medical leave for six weeks. Today, he writes about the medical emergency that sidelined him. He will return to his regular Slice schedule on Sunday.

When I got home from work, my wife feared I had suffered a stroke.

I was jumbling my words and showing other signs of incoherence.

It was nothing, I assured her.

I was wrong.

It was late Friday afternoon, June 19. The day my wife saved my life.

An abscess in my brain was wrecking my ability to use language and maintain my balance. I had first realized I was not well the previous Sunday night. But I thought it was a wicked summer cold.

I might have called in sick the next day, June 15, but a friend was meeting me at the paper a little before 7 a.m. We were going to take a selfie together up on the roof of the Chronicle Building. I did not have her phone number with me at home.

So I got up Monday and rode my bicycle downtown.

By midmorning, I realized I had zero energy, even for a 60-year-old. I emailed my editors and said I didn’t feel well and would be back Tuesday.

Though normally obsessive about riding my bike, I left it at work and took the bus home on a sunny day. That was a loud alarm bell, but I could not hear it.

The next three days were mostly a blur. I repeated my assurances to my wife that I just needed rest. I rode the bus downtown and back each day.

But by Friday afternoon, Carol, my wife, was adamant that I be seen by a doctor. Either that or she was calling 911.

After another round of foot-dragging, I agreed to be taken to the walk-in medical clinic on 29th Avenue. You know, to humor her.

If I had been in my right mind, I would have seen that something was wrong.

Earlier, at work, I had found myself forgetting how to accomplish simple tasks on my computer – things I had done thousands of times.

Friday is the day I write columns for Monday and Tuesday. But I couldn’t remember which one I was working on. The words on the screen before me were faint images of thoughts I had already forgotten. My editor found three errors in that Tuesday column, and she’s fond of saying I don’t usually make her work that hard.

By evening, it only got worse. When I attempted to fill out the information sheet at the clinic my handwriting looked like a first-grader’s and what I wrote made little sense.

When Carol and I stopped by that clinic several weeks later to thank the doctor who steered me to the Sacred Heart emergency room, he showed us the form I had tried to fill out. It was almost funny.

Almost.

So we drove down the hill to Sacred Heart. And a few hours and several diagnostic tests later Carol was hearing scary assessments of my prospects. Some doctors and nurses had shifted into empathy mode. Someone floated the word “inoperable.”

If I heard any of that, I don’t remember. Reality had yet to sink in. In any case, I assured Carol that all these tests were just a way of “covering their ass.”

Which would have been a fine theory, except for the rapidly growing mass in my brain that was crowding out my ability to choose and remember words.

Much of what took place over the next 10 days in the hospital, I cannot recall. Carol ought to be writing this. She was there in a way I was not.

Drifting in and out of a drugged haze and sleeping for extended stretches, I was a bystander at my own health crisis.

It’s safe to say, though, I did not have a keen grasp of my circumstances. When my mother-in-law and sister-in-law arrived from Michigan that first weekend, I was not quite sure why they had come.

Sure, I was in the hospital. It was serious. But were we at that stage?

Truly bad things just afflict other people.

In any event, here’s what happened in a nutshell.

A brilliant neurosurgeon tunneled a needle inches into my brain and drained most of what turned out to be a strep infection that probably started in my mouth. (You have some in your mouth, too. We all do.) The bacteria’s journey to its eventual destination near the thalamus is harder to explain. My internist calls it “weird.”

But here is the thing. From the moment my brain infection was discovered back on June 19, every single thing has gone my way.

I’m told the surgery was a minor miracle, though the neurosurgeon denies this.

My recovery has been faster and more complete than anyone would have predicted. When I was rallying after my operation, the initial plan included several months of rehab at St. Luke’s. By the time I was discharged from Sacred Heart, I was deemed fit to go straight home.

I watched “Jeopardy!” and found I had about the same batting average I’ve always had.

At first, TV remotes and smartphones were somewhat mystifying. That, I’m pleased to report, has gotten a bit better.

After some trepidation on my part, the keyboard welcomed me back.

I go for walks and even take gentle, old-man bike rides. When I’m not going to medical appointments, that is.

I’ve lost muscle strength in my legs and upper body but I am grateful for, well, everything else.

My experience probably has not left me with a lasting Zen-like outlook on life. Just ask Carol. I’m probably less patient. But it is not lost on me that I have been handed an opportunity to be a better, more aware man. What I do with that is up to me.

A follow-up MRI earlier this week showed I was no longer a head case. That was the news I had hoped to hear.

I’m still taking what has been referred to as “massive” doses of I.V. antibiotics via a tube attached to my right arm. I have a little titanium in my skull now, beneath where my stitches and staples once were. Still, all things considered, I am astonishingly fortunate.

Not everyone is.

When I was in the hospital, on my way to countless tests, I was wheeled past families that had gotten bad news. The worst news.

Why their loved ones and not me? I can’t answer that. All I know is when someone says everything turns out for the best, it is not always true.

It did for me. This time around.

I’m feeling fine. And I now possess a special gift: the knowledge that there are people, all kinds of people, who care about me.

Those patients who were not headed for happy endings, I hope they knew that, too.