Spokane’s identity is so deeply entwined with the world’s fair it hosted 40 years ago, and the massive transformation in its wake downtown, that it’s difficult for some to remember Spokane as it once was: the steel heart of a powerful mining and lumber region.

The 100 acres now known as Riverfront Park were once thick with rail lines and industry. The river’s falls were used to grind wheat and saw wood before being yoked to millworks and power plants. The Inland Empire boomed, and the river running through its core was engulfed by concrete, metal and activity, out of sight and easily forgotten.

When Spokane voters mark their ballots this fall, they’ll be asked to remember, and invest, in the river. The ballot measure will ask voters to finance a $60 million bond, which needs 60 percent to win approval, to renovate and update Riverfront Park. It is the largest park bond proposal in the city’s history. If passed, part of the money will go to fixing long ignored problems: the failing bridges, cracked sidewalks and leaky ceilings.

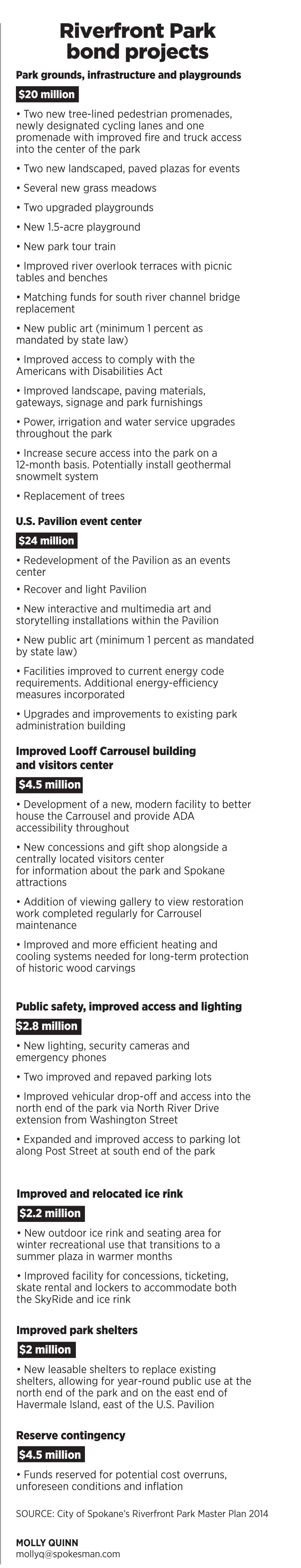

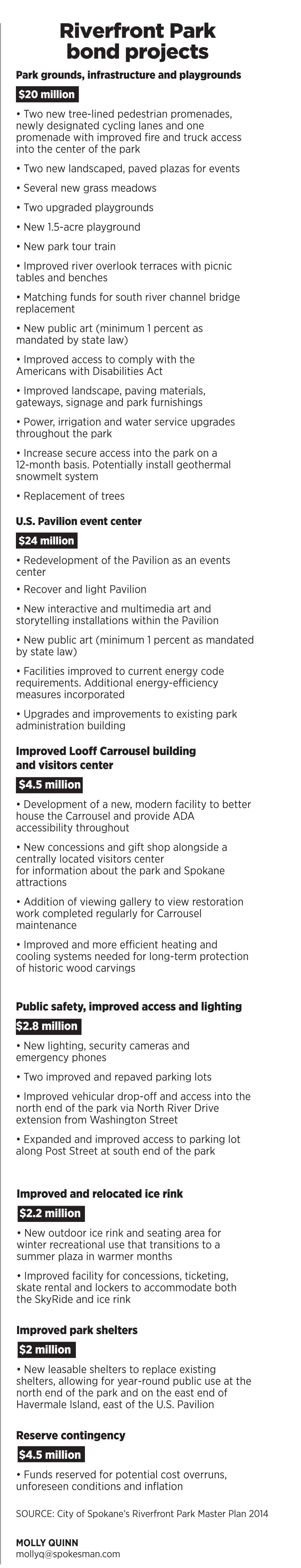

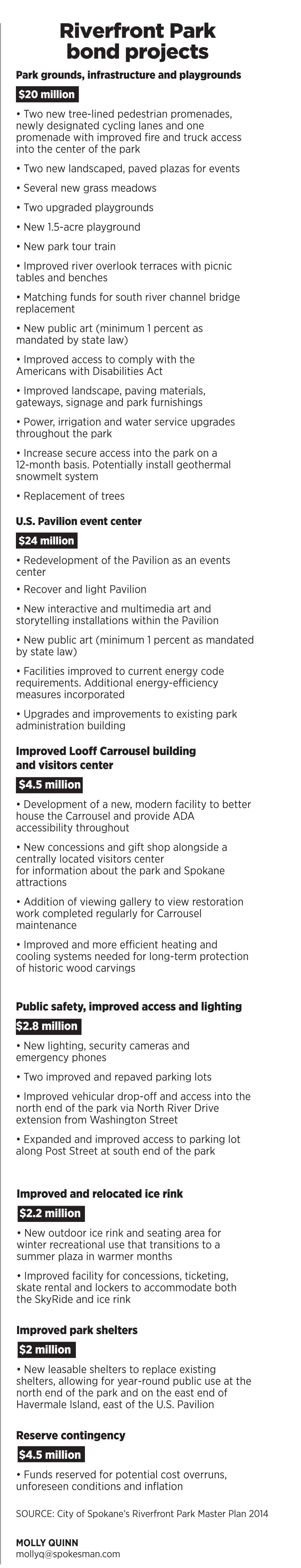

But most of the funds will go to remaking the park for a new generation, creating a central plaza and promenade, reviving the Pavilion as a year-round event center, constructing a new home for the historic Looff Carrousel, building an ice rink near City Hall on the park’s southwest edge and lighting the park for safer strolls at night, among other things.

“We want that spot in our community to serve as a gathering place, a place for entertainment,” Mayor David Condon said. “The question driving this is: What is this generation of voters and workers and parents going to leave for our kids?”

J. William “Bill” T. Youngs, a historian at Eastern Washington University who wrote the definitive history of Expo ‘74 in “The Fair and the Falls,” said it’s about more than legacy.

“Nature gave us the falls but at various times we’ve diminished them,” he said. “Now we’re trying to change that.”

Paying for Parks

When he took office, Condon looked into hosting another world’s fair in Spokane, a massive undertaking that he decided was ultimately impossible.

“I wondered if I could be the mayor to bring back the world’s fair,” Condon said. “It’s scheduled out till 2023 so even if I did win re-election, I wouldn’t be around for it.”

Instead, Condon formed a group of 20 people representing business, academic, environmental and public organizations to look into renovating the park, which eventually led to November’s bond measure. It was chaired by Ted McGregor, founder and publisher of the Inlander.

Over the course of the next year, they put together a wish list of what they wanted to see in the park, from extending the gondola to the convention center to erecting a viewpoint atop the clock tower.

But city leaders didn’t want to raise tax rates, and Condon told the group its budget was limited to $60 million, which would be raised by a vote of the people and paid for with the city’s bonding power.

Today, residents pay 34 cents for every $1,000 of assessed property value for voter-approved park taxes, which amounts to about $44 a year on a $130,000 house, the median home value in Spokane. The money currently goes toward paying off two park bonds, including one from 1999, which is set to be paid off at the end of the year.

If this year’s bond is approved, residents will pay the same rate - 34 cents per $1,000 of property value - to continue paying on a 2007 pool bond debt and finance $60 million for Riverfront Park. If it doesn’t pass, someone with a $130,000 house would see their property tax rate drop by less than $12 a year.

“Will you agree to paying what we are paying right now for 20 years?” said Randy Cameron, the president of the city’s park board. “Or do you want to pay a little bit less for 13 years and get nothing out of it?”

“It is not a tax rate increase,” said City Council President Ben Stuckart, who was part of McGregor’s group and is heavily involved in the campaign to pass the park bond, like Condon. “Your rate will stay exactly where it is right now.”

Proponents of the park bond have raised about $22,500, according to data from the state’s Public Disclosure Commission. The biggest donors to the campaign, which also promotes the street levy on November’s ballot, are the Spokane Regional Convention and Visitors Bureau, CPM Development Corp. and the Cowles Co., which owns The Spokesman-Review. Each gave $5,000.

While there’s no organized opposition to the measure, Councilman Mike Fagan said he won’t vote for it despite approving of the plan.

“I believe the park bond is a good thing. The plan is a good thing,” he said. “Is it the right time? That’s where I have to draw the line.”

Fagan said he will vote for the 20-year street levy on the ballot, but noted that voters hadn’t been given enough information to “prioritize” how they want public money to be spent. He listed a number of “tax asks” in the coming years: a potential bond for Spokane Transit Authority’s $70 million Central City Line and a multimillion-dollar Spokane Public Schools tax measure in February, among others.

McGregor said the money’s more than suitable for his group’s plans, but pointed to projects in other cities with much higher price tags: a $490 million investment in Chicago’s Millennium Park, and $172 million for the High Line in New York City. Even the original investment in Riverfront Park is estimated to have cost $115 million at the time, about $581 million in today’s dollars.

In April, Tacoma voters approved a $200 million bond for improvements in all the city’s parks, primarily at Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium.

“Other cities are investing,” McGregor said. “It’s not a competition, but it’s worth noting.”

The 100-year plan

Kris Dinnison is a local author and, with her husband, Andy, owner of two popular downtown businesses: Boo Radley’s and Atticus. She was part of McGregor’s group and the discussions they had helped her realize that Riverfront Park is the city’s “hearth,” a gathering place where the “story of our community” is told.

If it’s true, Spokane’s story is told to more than those who live in the city. According to a study commissioned by the city, the park attracts 2.2 million visitors a year.

“Anytime anyone comes to the park, they’re going to go through downtown,” Dinnison said.

The economic ramifications for downtown, the city and the region as a whole are hard to gauge. But the river’s economic benefits have always been a factor, for the natives who pulled fish from its waters to the city founders who contemplated empire.

“Where John Muir might have said let’s preserve it, Spokane’s founders said let’s make money off it,” said Youngs, the historian. “But as the world has progressed, we’ve gotten more and more attuned not only to the beauties of the world, but also to the financial benefits of beauty.”

The park plan delves into many modern-day details: a geothermal snowmelt system, a plan to plant a tree for each tree that is removed, walkways that comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act, surveillance cameras. Despite such details, the plan is rooted in the original conception of the park by the Olmsted Brothers, who envisioned a network of parks in Spokane - including a Gorge Park centered on the falls - more than a hundred years ago.

More than 60 years before Expo ‘74, the Olmsted plan recognized the importance, and difficulty, of developing a park at the city’s core.

“The river gorge within the built-up part of Spokane has already been partially ‘improved,’ as one might ironically say, but it is questionable whether any considerable portion of the community is proud of most of these improvements,” they wrote in their 1908 report. “Spokane should certainly preserve what beauty and grandeur remains of its great river gorge.”

McGregor said the new plan will bring Riverfront Park more in line with the Olmsted vision.

“It brings the river front and center,” McGregor said about the plan. “For 100 years, we tried to pave it over. Now the river is becoming the focal point.”

McGregor, who is not involved in the official campaign for the bond, said he could list countless reasons why people should vote for it.The park hasn’t been invested in since Expo ‘74. It could fuel economic development downtown. But most importantly, he said, citizens have a responsibility to maintain public space.

“It all comes down to, what kind of city do we want to live in?” he said. “I hope people think a little bigger.”

Judging by the opinions in the park on a recent sunny afternoon, not a lot of people knew what the bond would do, but almost everyone said they’d support it.

Harold Zaagsma was riding in a mobility scooter with his Chihuahua, Cinnamon, on his lap. He said the cracked paths were his largest concern.

“It’d be nice if they rebuild the walkways,” he said. He added that he was worried any new structures in the park would look too modern, changing the character of the park. He hadn’t made up his mind. “I might vote for it,” he said.

Kate Danvers also was undecided, but leaned toward yes.

“It’s probably a good thing,” she said of the bond. “But I don’t want to see the park get too commercialized.”

Belinda Ybarra, walking on her lunch break, said a revitalized park “would be awesome.” Jimmy Mack said as long as the plan maintains the park’s “peacefulness, friendliness and open space” it had his vote.

Neal Voss was wandering around the park with his wife and friends visiting from out of town. He stopped on the Howard Street Bridge near the fountain, which is partially barricaded from use due to weigh restrictions.

“I don’t see a downside,” Voss said of the plan. “You can’t close your eyes and let something like this slip away.”

Condon for one understands the park’s importance for many citizens.

“It transcends generations and political ideology,” he said. “Investing in the park is what we need to do and we’re the ones to do it.”

If approved, construction would start in 2015 and last four years.