Kootenai River projects beckon anglers

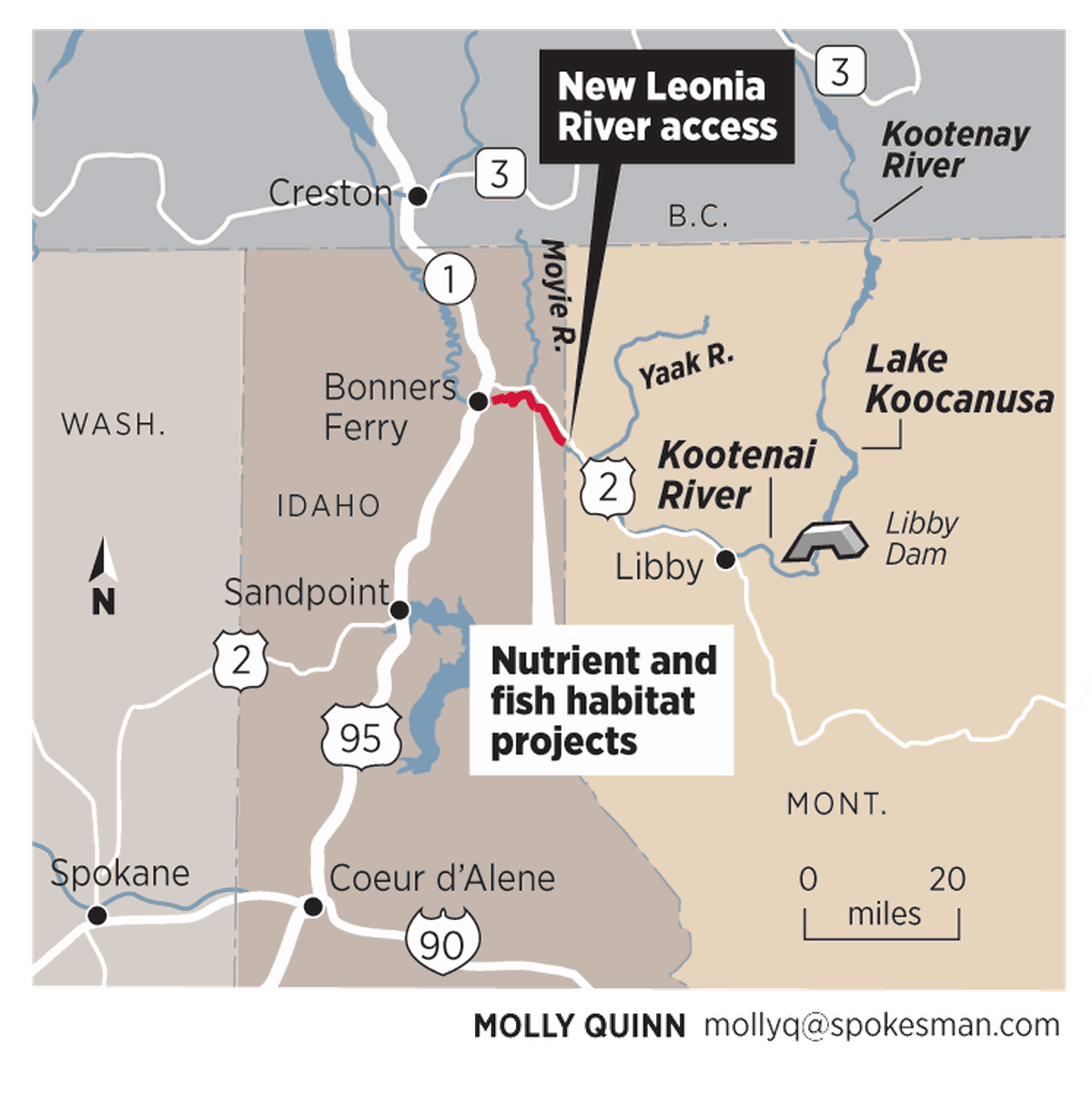

A new public access on the Kootenai River at the Montana-Idaho border opens the door for anglers to sample recent trout fishery improvements.

Meanwhile, a new Kootenai Tribe hatchery being dedicated in October at the confluence of the Kootenai and Moyie rivers aims to revive the native burbot – a freshwater ling prized by winter fishermen.

These projects and more are part of a multimillion dollar effort spearheaded by the Kootenai Tribe and Idaho Fish and Game to mitigate impacts to the river and boost fishing.

Two major projects funded by the Bonneville Power Administration are tending to the welfare of Kootenai River fisheries, which have been denied an adequate diet since Libby Dam went online in 1972.

Instream habitat construction is giving fish long-lost security. A river fertilizing program is fattening up the nutrient-starved food chain.

“It seems to be working,” said fly fisher Leeanna Young of Kent, Washington, as she caught and released one of a dozen or so trout – rainbows, cutthroats, cutbows as well as whitefish – she hooked that day.

She and her husband were camped at Twin Rivers Canyon Resort last week for a fishing and floating vacation. “I love this more than anything,” she said at the oars of her personal pontoon boat. “The new fishing access just makes it easier.”

Idaho Fish and Game officials, working with Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, negotiated a $20,000 three-year lease with a private landowner to reopen boat access off Leonia Road.

The access had been closed for more than a decade after river users trashed the place and wore out their welcome with the property owner.

“I hope the public respects this privilege,” said Rex Hoisington, who manages Twin Rivers Canyon Resort with his wife, Shelly. “This is great for floaters and for our business.”

When the resort is open, late May through September, Hoisington rents rafts and runs vehicle shuttles for floaters.

Boaters must float 12 miles on the Kootenai from Leonia to the resort, which is next to the new hatchery at the Moyie River.

“That makes a good day, Hoisington said. “Before the access opened, floaters had to start 5 miles farther upstream at the Yaak. That was too far, especially if you’re fishing.”

A couple of islands in the stretch provide camping opportunities, but the shoreline is mostly private land.

Hoisington also drives vehicle shuttles for anglers who run the broader river stretch – where much of the instream fish habitat has been constructed – from the Moyie River 7 miles downstream to Bonners Ferry.

“The three-year lease for the Leonia access is a test,” said Ryan Hardy, Idaho Fish and Game biologist assigned to the Kootenai project. “The owner wants to see how it goes.”

Fish managers already have seen how the $50,000-a-year nutrient enrichment is doing and they’re pleased.

A tube in the river near Leonia drips a daily dose of fertilizer from June through September, the main growing seasons for aquatic bugs and most fish.

Trout are most prolific – 1,500-2,000 fish per mile – in the Montana stretch of the Kootenai above Kootenai Falls, where they have more diverse habitat, Hardy said.

But nutrient levels steadily drop in the river downstream from Libby Dam. The water was virtually void of nutrients by the time the water reached Idaho.

The nutrient enhancement project that started in 2005 has made a dramatic improvement on the fishery from the Montana-Idaho line downstream toward Bonners Ferry. The fertilizer created more algae – “the good kind,” Hardy said. Algae feed aquatic invertebrates, which nourish the trout and whitefish.

By 2009, the rainbow trout fishery had increased from about 50 fish per mile to 300, Hardy said.

North Idaho’s blue-ribbon cutthroat streams, the St. Joe and North Fork Coeur d’Alene rivers, hold 400-600 trout per mile, he said.

“For the Kootenai, it’s a huge improvement and we think we can get a little more out of it with some tweaks here and there even though the dam still presents some limits to what we can do,” said Charlie Holderman, project manager and fisheries biologist for the Kootenai Tribe.

Surveys indicate that most of the trout in the Kootenai project area top out at 16 inches.

But Young caught several fish longer than that in one day of dry-fly fishing, including a cutbow measured and witnessed at 22 inches.

“Anglers are happy with the improvements, according to our surveys,” Hardy said. “They’re catching close to a fish per hour. Statewide surveys indicate that’s a good measure of angler satisfaction.”

The Kootenai running through Idaho has few tributaries or trout spawning areas, but the nutrient enhancement appears to be boosting trout spawning upstream in Montana, he said.

Native mountain whitefish are the biggest beneficiaries of the nutrient project. “In the 90s we found 3,000 whitefish per mile and now there are 7,000 per mile,” he said.

“Whitefish are specialists with a mouth that can pick periwinkles off the rocks. They’re very prolific in areas of the river.

“Rainbows are higher up the food chain. We wouldn’t expect them to increase as much.”

Rainbow trout also are finding fuller plates at the Kootenai buffet. Young fished dry flies all day, starting with PMDs in the morning and hooking her first fish around 9:30 a.m.

Patterns imitating grasshoppers and the occasional huge October caddis – bouncing off the water like drunken hummingbirds – fooled fish most of the day.

Around 3 p.m., No. 14 Light Hendrickson patterns perfectly matched the tan mayfly hatch that brought trout heads to the surface until the sun broke out of the clouds.

“Since 2005, the abundance of macro-invertebrates like caddisflies and mayflies has increased about five-fold,” Holderman said.

“I’ve seen Pteronarcys californica (salmonflies) in July. That’s a good sign.”