App aims to alert parents to sign of rare eye cancer

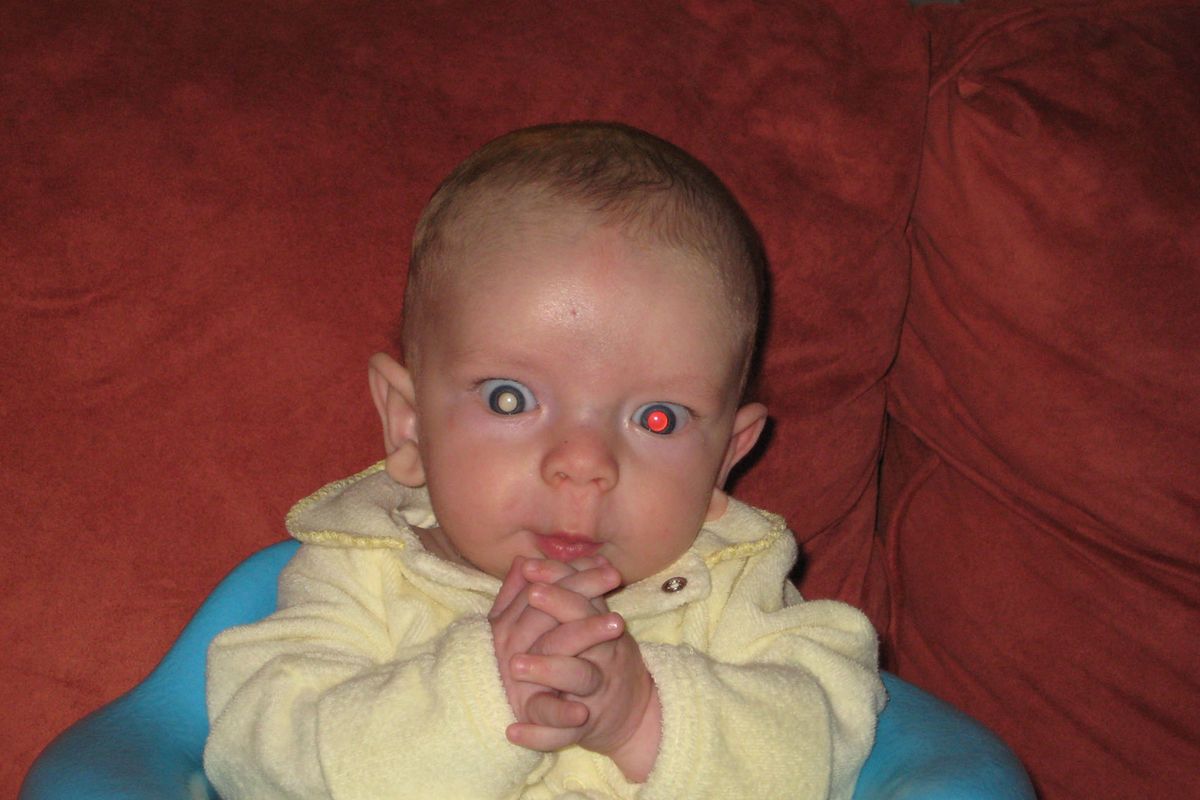

From left, Elizabeth, Samuel, Bryan and Noah Shaw are shown in a family photo from Easter. Bryan Shaw is a Mead High School and Washington State University graduate who has gained national attention for his work to develop a smartphone app that can warn parents of a white glow in a child’s eye that may signal retinoblastoma. Noah Shaw lost an eye to the rare eye cancer as a baby.

Bryan Shaw is a chemist, not a software developer. He’s a parent, not a doctor.

But he’s receiving national attention for his effort to create a free smartphone app to warn shutterbug parents of a glow in young children’s eyes – a white reflection from a camera’s flash – that could signal a rare cancer.

The iPhone app, called CRADLE, is still under review by Apple. But Shaw, a Mead High School graduate, sees its potential as huge: saving children’s vision in the U.S. and their lives in poor countries, where retinoblastoma is more likely to be identified only after the cancer has spread to their brains.

Shaw thinks big, and his project has been the subject of stories by National Public Radio and Popular Science.

But he also thinks broad. A researcher at Baylor University in Texas whose main work centers on protein science and ALS, Shaw delved into software development because he saw a need, but also because, to him, science is a big-picture pursuit.

As a post-doctoral researcher at Harvard University, he watched fellow chemists work on robots and flame control – not the stuff of a typical chemistry lab.

“That sort of gave me courage,” Shaw said. “ ‘You can do this. You just have to find the right people to work with.’ ”

His academic advisers – starting at Washington State University, then at University of California, Los Angeles, and finally in the renowned Whitesides Research Group at Harvard – were unconventional scientists, he said: “They did not respect boundaries. They did work outside their traditional fields.”

A willingness to experiment

As a scholar, Shaw has been unconventional from the start. His grade-point average at Mead: 2.9.

“Science needs rebels,” he said. “And you learn how to be a rebel when you’re a kid.”

“I think he partied the night before he took the SAT,” said his father, Denny Shaw, of Spokane.

But as a high school student, Shaw knew one important thing: When you understand the world at a molecular level, you really understand it. He launched himself into chemistry classes at Mead.

Laura Gray, his chemistry teacher there, said she remembers him well. She expected him to become an artist.

Shaw was a painter who once made a picture of molecules to present to her – “such a sweet gesture,” Gray said – which he accidentally drove over after leaving it on the roof of his car.

But there are links between art and science, she said – success in both fields require creative thinking. That came naturally to Shaw, she said.

And at WSU, Shaw got serious about school. He said he moved out of his fraternity house and started studying “all the time.” He met a scientist who spurred his interest in research.

“He called me up one day, and he said he saw a chemistry professor down there who’d studied under somebody who’d gotten the Nobel Prize,” Denny Shaw said. “He said he jumped out of his apartment window and ran this guy down and said he wanted to start studying under him.” The window, he added, “wasn’t way up.”

The chemist, Jim Hurst, remembers Shaw as a “colorful character” who took a research scientist from Japan to shoot guns at a quarry. And “then they had some stun guns at one time,” he said, “and Bryan decided he wanted to know what it was like to get hit by a stun gun.”

But Shaw’s willingness to experiment, Hurst said, has paid off in research labs. At UCLA, his former student was instrumental in developing a major new theory about how amyotrophic lateral sclerosis might begin and progress in brain tissue.

“Bryan has always been able to impress people with his freethinking and his courage in coming up with new ideas, new explanations for thorny problems,” Hurst said.

Shining a light on ‘the glow’

Shaw’s baby’s problem started small. His wife, Elizabeth Shaw, was the first to suspect something was wrong. She’d read about “the glow” in a parenting magazine.

Leukocoria, or “white pupil,” may be visible only in certain circumstances, such as in a darkened room. Sometimes it’s visible in photographs – while one eye has a normal “red reflex,” or red eye, the other has a white reflex.

Elizabeth had spotted the glow in some of Noah’s baby pictures. It was nothing, Bryan assured her.

But at his 4-month well-baby visit, Noah’s pediatrician peered into his eye with a bright light and saw the same white reflection Elizabeth had spotted.

An ophthalmologist made the diagnosis immediately. While retinoblastoma affects most children in just one eye, Noah had it in both.

His doctors used laser therapy and cryotherapy and chemotherapy to blast and freeze and try to shrink the tumors. But by the time Noah was 9 months old, the large tumor in his right eye was seeding – multiplying – in the fluid in his eyeball. With the cancer threatening to spread to the optic nerve and then to the brain, the eye would have to come out.

After the surgery, radiation on the baby’s left eye required general anesthesia, with its attendant risks, for each of his 30 doses.

So the parents focused on Noah’s treatment.

But Shaw eventually started thinking in another direction, too, back to those photos his wife had pointed out.

He dug into Noah’s many baby pictures, looking for the white glow. He found the first instance in a photo of Noah at 12 days old. By the time the baby was a few months old, the glow was appearing in all his photos.

“That’s when I realized that parents need help,” Shaw said. If there were some software available alerting parents of white eye in a picture, it wouldn’t go overlooked.

He approached “the glow” as a scientist.

That meant establishing that leukocoria could be a symptom of “early, early stage retinoblastoma,” Shaw said, when doctors have a better chance of saving children’s eyes.

It also meant defining white eye in a way that could be measured. So, working with other scientists, he created a scale to measure the intensity of leukocoria as it showed up in photos.

Then they wrote software to scan all the photos on a parent’s phone for those showing white eye.

The app can’t tell the difference between “fake leukocoria” – effects created by the camera – and a white glow that indicates a real problem.

“It doesn’t freak you out and tell you to go see a doctor,” Shaw said. “It just says, ‘Hey, we just want you to know you have white-eye pictures on your camera, and these can be no big deal and they can be symptoms of a serious eye disease.’ ”

Rare disease, worried parents

While white pupils can indicate other problems, such as congenital cataracts, retinoblastoma is “exceedingly rare,” said Dr. Caroline Shea, of Northwest Pediatric Ophthalmology in Spokane. The vast majority of children are diagnosed before age 5 and most before 3.

There are 11.8 cases for every 1 million children up to age 4. By another measure, she said, retinoblastoma affects one child in every 20,000 to 40,000 live births, depending on whose numbers you use. In Washington, that would mean roughly two to four cases a year.

But as more parents snap more digital photos of their children, doctors are handling more false alarms, she said. Parents – alerted by magazine articles or “Know the glow” campaigns online – are concerned white eyes in their children’s photos indicate cancer, when in fact they’re just seeing an effect created by their cameras.

“Obviously, early detection is better,” Shea said. “But what’s going to be detrimental to any screening process is … a whole bunch of false positives.”

Pediatricians check children’s eyes at every wellness exam as standard procedure, she added, referring them to ophthalmologists if they see anything out of the ordinary.

But Shaw said some studies have suggested most retinoblastoma diagnoses are initiated not by pediatricians, but by parents concerned about persistent white eye.

“A parent is scanning their child’s retina dozens of times a day, sometimes,” he said. “Every time you take a picture of your kid’s face, you’re scanning their retina. And you’re doing it at numerous angles.”

Spokane resident Julie Mosey’s 2-year-old daughter, Scarlet Mosey, was diagnosed with retinoblastoma this summer after a neighbor spotted a glow in her left eye.

Before that, Mosey said, she and her husband, Dawson Mosey, had seen something strange in Scarlet’s eye a few times. They’d do a double-take and it would be gone, she said. They never spotted it in photos – although, looking back, she said, it was detectable in photos from Scarlet’s second birthday party.

Scarlet has started chemotherapy. She may lose her eye.

“There’s a tremendous amount of guilt, not knowing what you’re looking at,” Mosey said.