Local volunteer leaders make world go around

Virtually all presidents are underpaid, unappreciated and overworked servants to their job.

We’re talking about presidents of the local organizations: the men and women who stepped up often because nobody else would.

Hikers, bikers, climbers, birders, boaters, skiers, mushroomers, backcountry horsemen, hunters, anglers, conservationists – every outdoor niche has an organization of enthusiasts, usually fueled by a handful of devotees and piloted by a president.

God love them.

Fly fishing clubs fund fisheries conservation projects and take kids fishing.

Hunting clubs put muscle into building fences to keep cattle from trashing habitat and raise money to buy radio collars for wildlife research.

Nordic skiing clubs have been the throttle for developing and maintaining groomed trail systems that are enjoyed by thousands of people who never lend a hand.

Society should find better ways to thank all of the people who join, pay dues and support organizations that serve the outdoors. These groups make our lives richer by their stewardship and helping others develop skills, ethics and access.

It’s a pity that we’re transforming into a nation of non-joiners. Being a non-member often is a cop out, a bit of selfishness, a commitment to reaping the benefits while others do the work

Being an independent has the downside of forfeiting your voice. By not joining, you often consent to letting others make the decisions. Many fishing and hunting rules, for example, are adopted because of testimony and support from organizations.

The world is ruled by people who show up.

Often that boils down to the groups led by presidents.

Nowadays almost any dedicated individual who wants to take the helm of a club can do so by raising a hand.

If a nominating committee can round up a prospect, the candidate usually runs unopposed. Votes often are unanimous in a quick ceremony before the nominee has a change of heart – or can take off the handcuffs and gag.

Nevertheless, some clubs get things done with the efficiency of a well-oiled corporation thanks to presidents and supporting members who selflessly share their time and professional expertise.

Spokane has numerous valuable outdoor advocacy groups, but none stands out with more distinction than the Dishman Hills Conservancy and its short list of fully invested leaders.

Founded in 1966, the group’s first torchbearer was Tom Rogers, a high school science teacher who drove around collecting newspaper and cans to recycle for funds to get out the newsletter, which was written mostly by him. He was deeply involved with the group until he died in 1999.

Perhaps the highest praise for leaders’ efforts is the quality of their mission and the people they inspire.

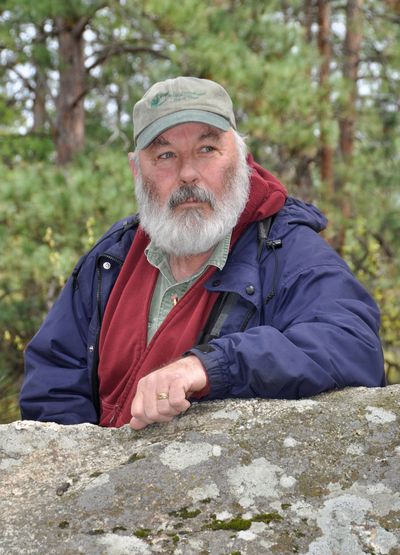

In 1991, Michael Hamilton, a Spokane geologist, was elected to the Dishman Hills group’s board. Two years later, he was elected president and led the organization into a golden period of Spokane County conservation efforts.

With the patience of a man fascinated by the impacts of wind erosion on rock, Hamilton worked with landowners, state and county agencies and other groups. A total of 1,721 acres was acquired directly or indirectly through his leadership in the Dishman Hills including Iller Creek, Rocks of Sharon, Big Rock, Glenrose and other properties that are now permanently protected for the public and wildlife.

The public benefit of such volunteer tenacity and commitment is huge.

Hamilton offered some insight.

“The secret to effective management is to spread out the responsibilities,” he said, referring to his success with the Dishman Hills group.

“Twenty years ago, we were in a transition. The membership was old and fading away. We had a surge of interest in the association around 2004 with the land acquisitions we were involved with near Tower Mountain.

“The Spokane Mountaineers stepped in big time with our interest in Big Rock (a popular rock climbing area),” he said, emphasizing the need for working with partner groups and agencies. “Spokane County Conservation Futures Program is having great results and state funding has made a critical difference.”

Hamilton should be proud of his tenure and the future of dream projects in the Dishman Hills.

“Now we have 15 fantastic board members with a lot of interest,” he said. “We had 530 people turn out a few years ago for our Dishman Hills service day when it was sponsored by REI.

“What amazes me is the support that’s out there from different corners of the public and people who believe in what we’re doing. Once I opened an envelope and found a check for $10,000 from someone I didn’t know. That signifies trust.

“That may not be a person who’s out here building trails and planting trees. But we need all kinds.”

January marks a new year and transition for many clubs as new presidents assume the gavel. The Dishman Hills Conservancy is among them, after electing new president Jeff Lambert, another time-proven stalwart conservationist, and hiring for the first time an executive director, Eric Robison.

Michael Hamilton, 68, has stepped down as president after 20 years.

But he didn’t step down far. “I’m the vice president, now,” he said. “Still actively involved.”