Efforts underway to make alternative transportation options easier in Spokane

By bike: Sharon Yablon commutes from Spokane’s North Side to her job on the 700 block of East Sprague. (Dan Pelle)Buy a print of this photo

After hay bales were piled inside streetcar No. 202 and its blaze reddened the sky, after the flames were doused by firefighters and their six bathing suit-clad assistants, the day belonged to the bus.

Billed as both celebration and commemoration, the public burning drew a crowd of 10,000 on Summit Boulevard in Spokane’s West Central neighborhood on Aug. 31, 1936. The event at Natatorium Park did more than mark the final journey of one streetcar in Spokane, which reportedly had logged more than 1.6 million miles during its 26 years of service. It marked the end of an era.

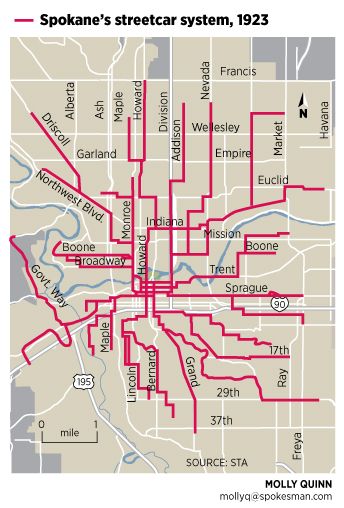

For 50 years, streetcars had transported the vast majority of Spokane’s people to work, to the store, to church, to school, to visit friends, to the park – to just about everywhere they wanted to go.

So it’s no surprise the mood was downcast that day as people watched the past go up in flames. The sentiment quickly shifted, however, when fireworks shot into the air and three of the city’s new buses turned on their engines. Planes roared overhead, the crowd cheered and a new era in Spokane transportation officially had begun. It was marked immediately as hundreds of cars crawled away from the packed event.

Local transportation officials say we’re on the cusp of another era, but it won’t be as sudden a shift, and it likely won’t be marked with such pomp.

“We are just at the beginning of this change,” said Kevin Wallace, executive director of the Spokane Regional Transportation Council, which helps coordinate the region’s transportation planning and doles out federal funds for projects. “The way we use transportation in 2040 is going to be very different than how we use it today.”

In the past decade, the average number of miles traveled in vehicles both nationwide and in Spokane County has continuously decreased, reversing an upward trend unabated since the car’s invention. No one expects the convenience or independence of cars to be usurped by another mode, but Wallace said all signs point to people driving less and seeking other ways to get around.

Commuters in Spokane already walk, take the bus or ride bikes. Local agencies are working to transform a system that has long been centered on the car to one that reflects not only how we move but also how we say we want to move. Just a few of the transportation initiatives in the works include launching 20 years of arterial street projects afforded by last month’s ballot levy; updating Spokane’s bike and pedestrian master plans; discussing a potential ballot measure for a tax to implement the Spokane Transit Authority’s Moving Forward plan; building the University District pedestrian bridge; adopting the National Association of City Transportation Officials’ Urban Street Design Guide as city policy; and the perennial push to fund – once and for all – construction of the North Spokane Corridor.

“You’re always building a system for tomorrow, but maybe not for 100 years from now,” Spokane Mayor David Condon said about not just the transportation system but how it ties in with other public works projects at the city. “What’s old is new again. The innovation is exciting, but when you look at some of the practicality of it, a lot of it you saw in our system 100 years ago.”

Busing it

Dennis Anderson likes the last seat on the driver’s side. It’s way back on STA’s long, articulated buses, a couple dozen paces past a normal bus-worth of seats, through the accordion-like joint in the bus’s center, past a few more rows of seats and up some stairs.

He makes sure to catch the bus at the downtown Plaza to ensure he gets that seat by the window. If he boarded at the Jefferson Lot below the highway, every seat likely would be taken and he’d have to stand the entire way to Cheney.

There he sits, after boarding at 7:40 each morning near his home on the South Hill, five days a week for the past 10 years, on his way to work at Eastern Washington University, where he teaches psychology.

“I really look forward to the opportunity to grade papers or read articles,” Anderson, 60, said about the ride. “From a psychological point of view, it helps reduce stress. At least, it reduces my stress, especially in the wintertime.”

As Anderson suggests, of all the ways to commute, riding the bus is easily the safest and most passive. Paying the fare is the most active thing you’ll do directly related to the ride. Mass transit is also the longest-running form of transportation in Spokane, if you don’t count walking or riding a horse.

Karl Otterstrom, director of planning at Spokane Transit Authority, is a one-man transit encyclopedia, which is especially helpful when he gives a tour of STA’s mini-museum in the second-story hallways above the agency’s Boone Avenue bus barn.

He said the city’s streetcars gave almost 38 million rides in 1910, a record that stands to this day. In the years that followed, autos and other new forms of transit threatened the streetcar’s monopoly. For instance, Spokane’s auto dealers would loan their cars out to young men, who would prowl the trolley lines and jam up to 10 people in one Model T.

“They were the uber-Uber,” said Otterstrom, referring to today’s taxi-like ride-share service hailed through a smartphone. The Washington Water Power company, which consolidated all streetcar service under the banner of Spokane United Railways in 1922, was seen as “the big bad corporation.”

Since 1936, Spokane has been served by bus. There have been changes – a 146-day strike in 1968 bottomed out the system, and it was made a public organization in 1981 – but as Otterstrom said, the network of routes is rooted in the original streetcar layout.

However, STA is considering its biggest change in a generation. Otterstrom calls it STA 3.0 – the agency’s third version, after the 1981 incorporation and the “big reset” in 1998, when the transit group lost a huge chunk of funding and had to rethink how it did things.

Still, Otterstrom looks to the future of the city’s transit system as he keeps one eye on the past. He helped author the agency’s comprehensive plan, which lays out its vision for the next 30 years and informs its “Moving Forward” plan, including service to new areas, more rapid transit corridors, new transit centers in places like the West Plains and more Internet connectivity for riders.

The details of the plans are many, but Otterstrom puts it simply: “Frequency is freedom.”

Since 2008, STA ridership has hovered around 11 million, up from the 20-year plateau of 7 million rides that preceded it. Otterstrom said he believes if the frequency of buses on some routes was increased, ridership would spike.

“There’s latent demand,” he said, noting that some routes – like the one to EWU, the North Division and East Sprague routes – are frequently standing room only. “That’s what’s so evident to the bus rider and so hard to understand for people who don’t ride the bus.”

The aspect of the plan that has received the most attention is the Central City Line, a fixed-route electric streetcar that would run on rubber tires from Browne’s Addition through the University District and end at Spokane Community College.

It cuts through the part of town – downtown – where on average 21,000 people get on or off a bus every day. Officials estimate the central line could garner more than 3,000 rides a day. It helps with transit “ubiquity” in the city core where a quarter of all bus transactions happen. As Otterstrom points out, however, that means three-quarters happen in other parts of the city.

Behind the wheel

Christina Huggins, 24, drives to work.

Partly, it’s for the independence, considering she’s young and may not know what she’s doing after work until it happens. She also usually works more than 40 hours a week between her two jobs, one at Atticus downtown and the other at Pier 1 on North Newport Highway. Her schedule doesn’t leave a lot of spare time.

Her car – a 1993 Mazda Protege – isn’t much to look at, but “it gets me from Point A to Point B when I want to go,” she said.

But she’s not just a driver. She drives from her home near Downriver Golf Course to Browne’s Addition, where she parks and makes the mile-long hike downtown, a way to avoid an $8 daily parking tab.

It may sound obvious, but like most people, Huggins doesn’t use just one form of transportation. It’s for this reason, city leaders say, that the street levy overwhelmingly passed by voters last month won’t focus its dollars only on car infrastructure.

“People would say, ‘Well you’re not guaranteeing that this is all going to go to streets in the traditional sense,’ ” Condon said. “I conceded. Amen. No, I’m not. We’re looking at each of these holistically. You need to look at every street in its entirety.”

With the previous 10-year street bond, which wrapped up this year, arterials were rebuilt “curb to curb,” meaning sidewalks, bike lanes and underlying infrastructure were left out of designs. Under Condon, the city has changed the way streets are built. Now it combines street work with utility work, repairing water lines and updating stormwater drainage systems while laying new pavement. The new concept allows for better pedestrian and bicycle facilities, when a street calls for it.

“I call them integrated streets. You’re looking at the different modes of transportation,” Condon said. “Indian Trail is going to look different than Perry. Rockwood is going to look different than Five Mile. And that’s fine. Actually, I think that’s pretty neat.”

By combining work and funds, the city expects to bring in about $500 million during the next 20 years. The levy also freed up the $2.5 million annually generated by the $20 vehicle license tab tax, which will be used to fix the city’s residential streets.

“We’re on the same page,” said Councilman Jon Snyder about Condon. Snyder, a noted bike commuter, led the City Council in 2010 to adopt a policy of Complete Streets, which is similar to Condon’s concept minus the underlying utility infrastructure.

In short, it lets how people use the street guide engineers when they’re fixing and redesigning the street. Condon points to the new stretches of South Monroe and High Drive as examples of this policy at work. Monroe was “right-sized” to one lane in either direction because traffic counts didn’t require a total of four lanes. The sidewalks, however, were rebuilt with updated ramps and are now separated from the street. On the other hand, High Drive got bike lanes.

Funding wars

This summer, Snyder threatened to hold the vehicle tab tax hostage in order to ensure the completion of the long-delayed Pedestrian Master Plan, which will guide how best to spend money to improve sidewalks and make roads safer for walkers. The plan was launched in 2011 but stalled a year later and never finished after staff changes in City Hall. Snyder sponsored an ordinance threatening to dissolve the city’s Transportation Benefit District – along with the revenue generated by the vehicle tab tax – unless the plan is finished by the end of 2015.

The ordinance passed, but Snyder soon brought the tab tax before the council again, this time to change language that had required 10 percent of the tax to be dedicated to pedestrian infrastructure. He said the committee that doled out the funds was confused by the language, seeing it as a target that had to be exactly met. Snyder recommended making it a minimum of 10 percent.

Council members Mike Allen and Mike Fagan argued that a top end should be codified as well, but their arguments did not persuade the majority, and Snyder’s ordinance passed unchanged.

“Most people use more than one mode,” said Snyder, noting that he is not anti-car, just for more robust transit choices. When people complain to him about traffic congestion, he tells them there are other ways to relieve the pressure than building and widening roads. He joked that one sure way to ease traffic would be to build an elevated highway over North Division.

“You could get from downtown to the ‘Y’ lickety-split,” he said. “And it would only cost $4 billion.”

Instead, he said, he prefers other, cheaper methods of reducing the number of cars on the road – primarily by making it more convenient to ride the bus or a bike.

Wallace, head of the transportation council, said a project’s price always has helped determine its fate, but how transit projects are funded has changed dramatically in recent years, and not for the better.

“It’s unanswered in our region. It’s unanswered in our state. It’s unanswered in our nation,” he said. “It’s the biggest issue we face.”

The city’s street levy, and STA’s potential ballot measure, are examples of local solutions in figuring out the funding puzzle, Wallace said, but the community can’t afford other, knottier projects.

For instance, of the county’s 377 bridges, more than 30 percent are either functionally obsolete or structurally deficient. It would take about $1.9 billion to fix every bridge.

“The region can’t do that on its own,” Wallace said. What it can do, he said, is make “the right investments in the right locations at the right time.”

To do that, Wallace said. transportation planners basically need to let data drive how decisions are made. At his organization, they’ve overlaid maps of transportation corridors, population growth, employment density, congestion, developable lands and collisions to identify the particulars of how we live and move, thus how transportation systems should be designed.

“Transportation really is a system,” Wallace said. “If you took transit out of the equation, you definitely would see more congestion; that’s why what STA is doing just makes sense. But I wouldn’t want to give up my car. We need all these options. That’s really what we’re trying to do by having all these choices.”

This time of year, when Sharon Yablon leaves her house, it’s dark. When she rides home, it’s dark, which explains the fluorescent clothes and blindingly bright front lamp.

It’s Yablon’s third winter as a bike commuter, something her co-worker at Spokane Housing Ventures, Eric Swagerty, helped get her into.

The snow and ice don’t get to her because her tires are studded and her clothes are warm. The traffic doesn’t get to her because she mostly rides along designated bike routes from her home in Hillyard, a 5-mile ride that takes about 30 minutes.

“The length is just perfect,” she said. “It actually takes me longer to take a bus.”

A primary part of her ride goes along East Illinois Avenue, which recently was remade by the city, with bike lanes.

“I’m very impressed with what they’re doing,” Yablon, 61, said about the city’s work to add bike infrastructure. “In Spokane, I think cars are pretty polite to ride with. About once a month, I get honked at for being where I’m supposed to be, but they don’t seem to understand that.”

The city is in the midst of updating its Bike Master Plan, and leading that effort is Inga Note, a planner who recently was hired away from Spokane Valley. At this point in the process, everything is on the table: raised bike lanes, separated bike lanes, neighborhood greenways where cars are discouraged to drive, wayfinding signs for bike commuters, lighted bike signals along routes and more.

Note said the primary goal is to attract the vast majority of people who are “interested but concerned” about riding, and she thinks adding some innovation into Spokane’s bike network would help convince the wary.

Councilwoman Candace Mumm agreed, dismissing any discussion about putting too much effort toward bike commuters, who make up less than 1 percent of the commuting population in Spokane, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The discussion of whether Spokane should encourage alternative forms of transportation has long been settled, she added, and plopped down the city’s weighty Comprehensive Plan as proof.

In Chapter Four, the plan lists its transportation priorities: “Design transportation systems that protect and serve the pedestrian first,” it says. “Next, consider the needs of those who use public transportation and non-motorized transportation modes. Then consider the needs of automobile users after the two groups above.”

Mumm, like Condon, said Spokane of the future could be like Spokane of the past.

“Look at an old photo of downtown,” she said. “There were people five deep on the sidewalks.”

As Mumm suggests, the ghosts of Spokane’s transportation past still linger.

Old streetcar tracks are embedded in stretches of road in West Central. Rocky pyramids mark the route of the Mullan Road, the first wagon road across the continent’s rocky spine. The water trough for draft horses trudging by Manito Park is now used for flowers. The steep incline of South Monroe Street was constructed for a cable car in 1890, but the technology only lasted through the harsh Spokane winters for five years.

The streetscape of Spokane can tell a lot of stories. But it’s the future that’s being written now, and probably always will be.

“We’re never going to be done with streets, believe it or not,” Condon said.