Former Washington Gov. Booth Gardner dies

OLYMPIA, Wash. (AP) — Booth Gardner, a two-term Democratic governor who later in life spearheaded a campaign that made Washington the second state in the country to legalize assisted suicide for the terminally ill, has died after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease. He was 76.

Gardner died Friday at his Tacoma home, family spokesman Ron Dotzauer said Saturday. He was the state’s 19th governor.

“We’re very sad to lose my father, who had been struggling with a difficult disease for many years, but we are relieved to know that he’s at rest now and his fight is done,” said Gail Gant, Gardner’s daughter, in a statement.

The millionaire heir to the Weyerhaeuser timber fortune led the state from 1985 to 1993 following terms as Pierce County executive, state senator and business school dean.

Since then, he had worked as a U.S. trade ambassador in Geneva, in youth sports and for a variety of philanthropic works. But his biggest political effort in his later years was his successful “Death with Dignity” campaign in 2008 that ultimately led to the passage of the controversial law that mirrored a law that had been in place in Oregon since 1997.

The law allows terminally ill adults with six months or less left to live to request a legal dose of medication from their doctors.

Gardner knew that he wouldn’t qualify to use the law because Parkinson’s disease, while incurable, is not fatal. But at the time, he said his worsening condition made him an advocate for those who want control over how they die.

“It’s amazing to me how much this can help people get peace of mind,” Gardner told The Associated Press at the time. “There’s more people who would like to have control over their final days than those who don’t.”

The Washington law took effect in March 2009, and since then more than 250 people have used it to obtain lethal doses of medication.

A documentary about that campaign, “The Last Campaign of Booth Gardner,” was nominated for an Academy Award in 2010. A biography published by the Washington state Heritage Center’s Legacy Project, titled “Booth Who?” — after a campaign slogan in political buttons created during his first run for governor — was published that same year.

William Booth Gardner was born Aug. 21, 1936, in Tacoma to his socialite mother, Evelyn Booth and Bryson “Brick” Gardner. According to his biography, he was first named Frederick, but a few days after his birth, his parents changed his birth certificate, crossing out Frederick and replacing it with William. While even Gardener reportedly didn’t know what led to that early confusion over his name, the change to William was believed to be a nod to his paternal grandfather, who had founded a successful plumbing and heating business in Tacoma. Even so, Gardner always went by “Booth.”

His parents divorced when he was 4 and his mother remarried Norton Clapp, one of the state’s wealthiest citizens who was a former president of Weyerhaeuser and was one of a group of industrialists who helped build the Space Needle for the 1962 World’s Fair.

Gardner had his share of tragedy: his mother and 13-year-old sister were killed in a plane crash in 1951 and his father, who had struggled with alcohol, fell to his death from a ninth-floor Honolulu hotel room balcony in 1966.

Clapp remained a presence in Gardner’s life, and though he was a Republican, he made significant donations to both of Gardner’s gubernatorial runs.

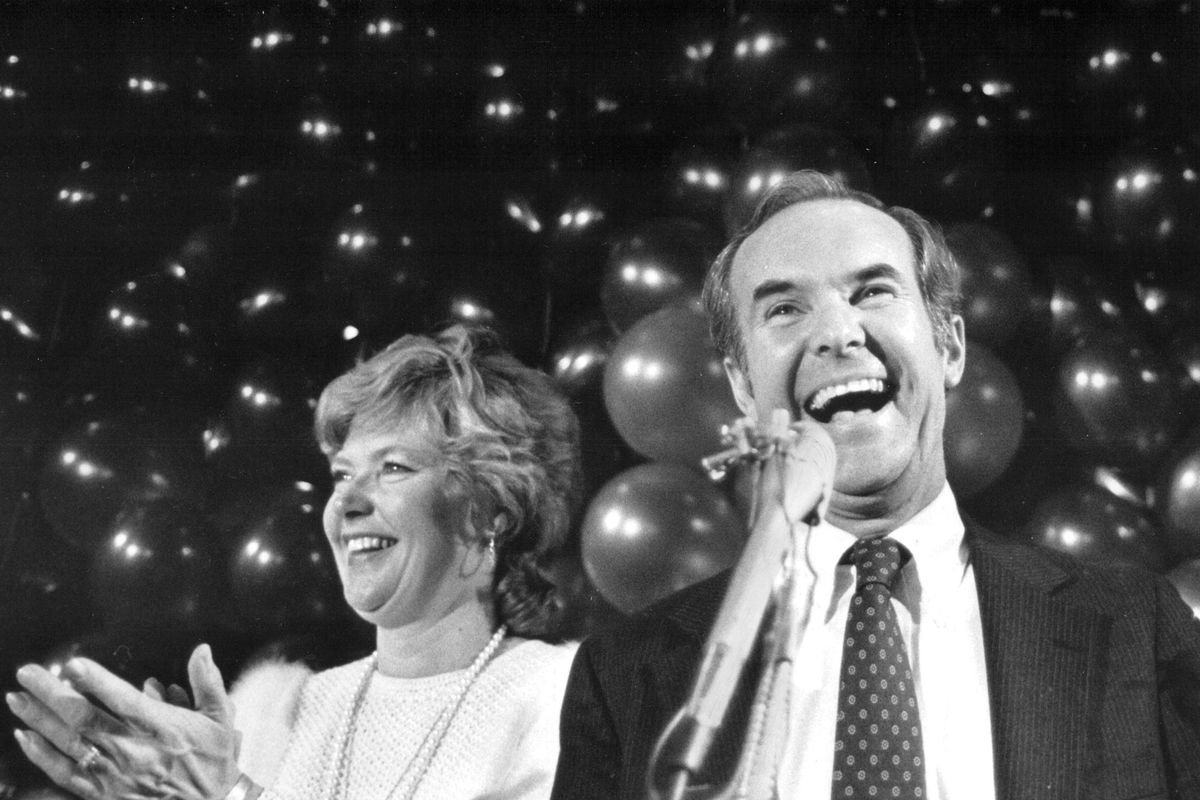

In November 1984, Gardner beat Republican Gov. John Spellman with 53 percent of the vote, winning 23 of the state’s 39 counties.

During his two terms, Gardner pushed for standards-based education reform, issued an executive order banning discrimination against gay and lesbian state workers, banned smoking in state workplaces, and appointed the state’s first minority to the state Supreme Court. The state’s Basic Health Care program for the poor was launched in 1987 and was the first of its kind in the country.

Toward the end of his first term, he appointed Chris Gregoire, then an assistant attorney general, as head of the Department of Ecology. Gregoire went on to be attorney general, and then governor. Gardner was easily re-elected in 1988, garnering 62 percent of the vote. In his second term, he and Gregoire, then attorney general, secured an agreement with the federal government that the nuclear waste at Hanford nuclear site would be cleaned up in the coming decades, and Gardner banned any further shipments of radioactive waste to Hanford from other states. The state Department of Health was also created under his watch.

In 1991, Gardner announced he wouldn’t seek a third term, saying he was “out of gas.” He went on to become the U.S. ambassador to the General Agreement on Tariffs & Trade in Geneva. While abroad, in 1995, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Gardner didn’t make his battle with the disease public until 2000, when he discussed it in an interview on TVW, the state’s public affairs network. That same year, he launched a clinic in Kirkland, the Booth Gardner Parkinson’s Care Center.

He announced his plan for a ballot measure to allow assisted suicide in 2006 as he continued to battle Parkinson’s. Twice in 2007, he traveled to the University of California at San Francisco for innovative deep-brain surgery that included implanting a type of pacemaker that helps restore control of his body.

Washington state had already rejected a similar assisted suicide initiative in 1991, but after a contentious campaign, where Gardner contributed $470,000 of his own money of the $4.9 million raised in support of the measure, nearly 58 percent of voters approved the new law in 2008.

In his biography, when asked how he wanted to be remembered, he responded, “I tried to help people.”

“I got out of the office and talked with real people, and I think I made a difference.”

He is survived by his son, Doug, his daughter, Gail, and grandchildren.

___

Associated Press writer Manuel Valdes contributed from Seattle.

Copyright 2013 The Associated Press.