For health care’s drive to reform, cost curve looms ahead

After Congress created Medicare in 1965, the program grew and changed. But since the ’60s, when courtly senators still referred to one another as “gentlemen,” the spirit in Congress has changed as well. What will happen when a need arises to reform the landmark health care law that Congress passed in 2010?

Mike Kreidler, Washington state’s insurance commissioner and a former member of Congress, shakes his head as he recalls the regular reforms that turned Medicare into what it is today. The polarization of today’s Congress doesn’t bode well for the program-friendly reform that made Medicare work better as the years went by, he said.

As a longtime advocate for health care reform, what does Kreidler think the 2010 law left undone?

Cost control. “I wish there had been more specificity for how to bend the cost curve down,” he says.

Karen Keiser, a state senator who advised the White House as it drafted the 2010 reforms, agrees. The 2010 law contains numerous provisions to make health insurance coverage more available and more affordable for consumers. But it “did not do anything innovative,” she says, to change the cost of medical care itself. “It is up to the states to do that,” she said.

Washington state’s Health Care Authority manages health coverage for state employees, plus health programs such as Medicaid for low-income people. The $14 billion it spends on health is second only to education in Washington’s current two-year budget. This makes the HCA an economic heavyweight and an influential model for change in Washington’s health care system.

With medical costs exploding and state revenue shrinking, the HCA has had an incentive to make fundamental moves toward cost control. Its response? Eighty percent of its Medicaid clients have been moved from a traditional fee-for-service system to a managed care system.

Fee for service, medicine’s traditional reimbursement model, pays for each procedure. The more procedures a surgeon or a laboratory performs, the more money they receive. And the more the system spends.

But managed care changes the reimbursement system. The most common technique is to pay provider networks based on the number of patients they enroll, not the number of procedures they perform. If a network provides preventive care and nips health problems in the bud, its patients stay out of hospitals and emergency rooms and the network saves money.

Medicaid, like corporate health coverage, actually is handled by private health insurance carriers; the HCA, just as large employers do, contracts with private insurance firms. What the HCA has done is specify that most Medicaid beneficiaries be covered by managed care policies.

MaryAnne Lindeblad, HCA director, explains: “When an organization is at risk for someone’s care, they have an incentive to make sure the person has the conversation with a doctor about issues like stop smoking, lose weight, exercise. But in a fee-for-service world, you don’t have that relationship or that conversation.”

The latest innovation, she says, is to assign patients to a “health home.” The health home is a buzzword, not for a doctor but for a team of care coordinators who know the patient: a nurse practitioner, for instance, or a social worker. These coordinators ask chronically ill patients whether they’re taking their medications, checking their blood sugar, making it to their appointments.

Techniques like these have huge potential for cost control, Keiser says: “We spend 80 percent of the cost on 20 percent of the people.” If the chronically ill understand a treatment plan to keep their disease under control, and if front-line care providers help them stick to the plan, costly emergencies can be averted.

The new federal law offers grants to encourage states to try managed-care techniques.

What about insurance carriers?

They face market incentives, if not mandates. The way they’ll use those incentives, however, is an open question.

Group Health predicts plenty of capacity

Group Health, one of Washington’s largest health insurance carriers, is unique in that it also is a provider, operating a statewide network of clinics and physicians. Scott Armstrong, Group Health’s CEO, declares flatly that “fee for service is flawed. It is inhibiting our system from ever achieving the better trends, quality and health we all expect.” In a traditional fee-for-service system, he said, primary care doctors “don’t coordinate very well at all” with specialists and hospitals.

Today, he says, “doctors recognize they need to be practicing as part of a bigger system. These independent fee-for-service systems just aren’t going to be around any longer.”

Instead, physicians and hospitals have been joining together in large provider networks that create an opportunity to coordinate care, from a simple checkup to advanced surgeries.

Group Health has tracked the effectiveness of focusing on upfront prevention such as making sure people take medications and tests to control cholesterol, blood pressure, asthma and diabetes.

Expanded access to primary care doctors, including giving patients the ability to email and call their providers, resulted in a nearly 30 percent drop in the number of times patients showed up in emergency rooms and a 20 percent drop in hospital bed use, Armstrong says.

“If your doctor and nurse are asking you, ‘Are you watching your weight and taking your meds?’ it is proved that the cost over time is lower,” he says.

But in the absence of insurance coverage – the status quo for more than 727,000 Washington adults – preventive care does not happen. Instead, people show up in emergency rooms when they’re desperately ill.

That’s why Armstrong welcomes the federal reforms: “Hundreds of thousands who should have access to care will have it. Then the costs to them and the state will be lower.”

So what happens when newly insured individuals begin showing up for care? Will doctors be overwhelmed?

Armstrong doubts it: Speaking only for his own system of clinics, he says, “We’re a really big system … we’ve got plenty of capacity.”

From a Group Health perspective, he says, “a significant percentage of work done in medical practices today shouldn’t be done. It is redundant or not supported by the evidence, or it’s wasteful. The access issue people talk about, available doctors, is going to be resolved when we pay doctors not for services but to promote better health.”

Potential danger in hoards of cash

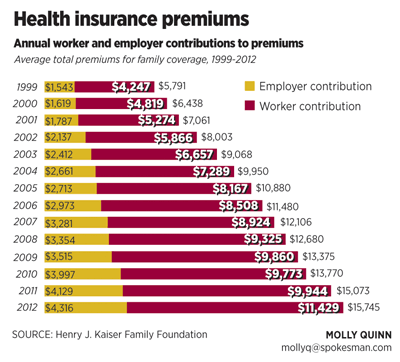

The federal law gives insurance companies a hard shove toward reducing their overhead costs, such as the amount they spend disputing their customers’ claims for coverage. For insurers selling coverage to individuals or small groups, the law requires that 80 percent of premiums go to medical care. For insurers selling to groups of 50 or more employees, 85 percent of premiums must go to medical care.

Still, Kreidler, the insurance commissioner, notes that neither the federal law nor his office can force private insurance plans to switch from fee-for-service to managed care.

The marketplace of insurance buyers, from the state Health Care Authority to those who will buy insurance on the new website, could make that decision when they evaluate costs and benefits of competing plans.

However, the emergence of large provider networks – managed conglomerates of doctors, hospitals, imaging services and labs – raises concerns in Kreidler’s mind. “As a regulator I’m fearful of the market power” a large network can play, he said.

Time magazine, in a Feb. 20 cover story, described the political clout large hospital networks wield to defend high fees and profits.

Meanwhile, the biggest, most powerful health insurance carriers in the state also have attracted Kreidler’s concern by amassing extraordinary hoards of cash. Premera Blue Cross and Regence BlueShield each have surpluses of more than $1 billion. This is considerably larger than what those carriers need to cover unexpected costs, Kreidler contends. Group Health also has a sizeable surplus, but Kreidler is less critical of that one because, unlike other insurance carriers, Group Health operates its own medical facilities and needs capital to expand and improve them, he says.

Kreidler has asked the Legislature to pass a law allowing him to consider these surpluses when insurance carriers propose the rates they want to charge consumers. Under current law, his actuaries cannot consider the surpluses at all. Republican legislative leaders, however, echo the insurance companies in opposing Kreidler’s request, arguing that insurers need big surpluses to cover unknowns related to compliance with the new federal health care law.

Kreidler fires back that the federal law already contains safeguards to protect insurance companies from unexpected costs: Three different bailout programs are prescribed in the law. These programs will provide reinsurance to shield carriers from extraordinary costs and will funnel dollars from carriers that get lucky and strike it rich from the reforms to carriers that experience bad luck in the transition.

“I have a deep, abiding concern for the financial viability of health insurers,” Kreidler said. “I want to see them succeed. At the same time, with the big surpluses, I should be able to at least slow down the increases.”