Idaho inmate accused of continuing fraudulent ways in prison

He’s accused of scheming to collect settlements from class-action suits, bankruptcies

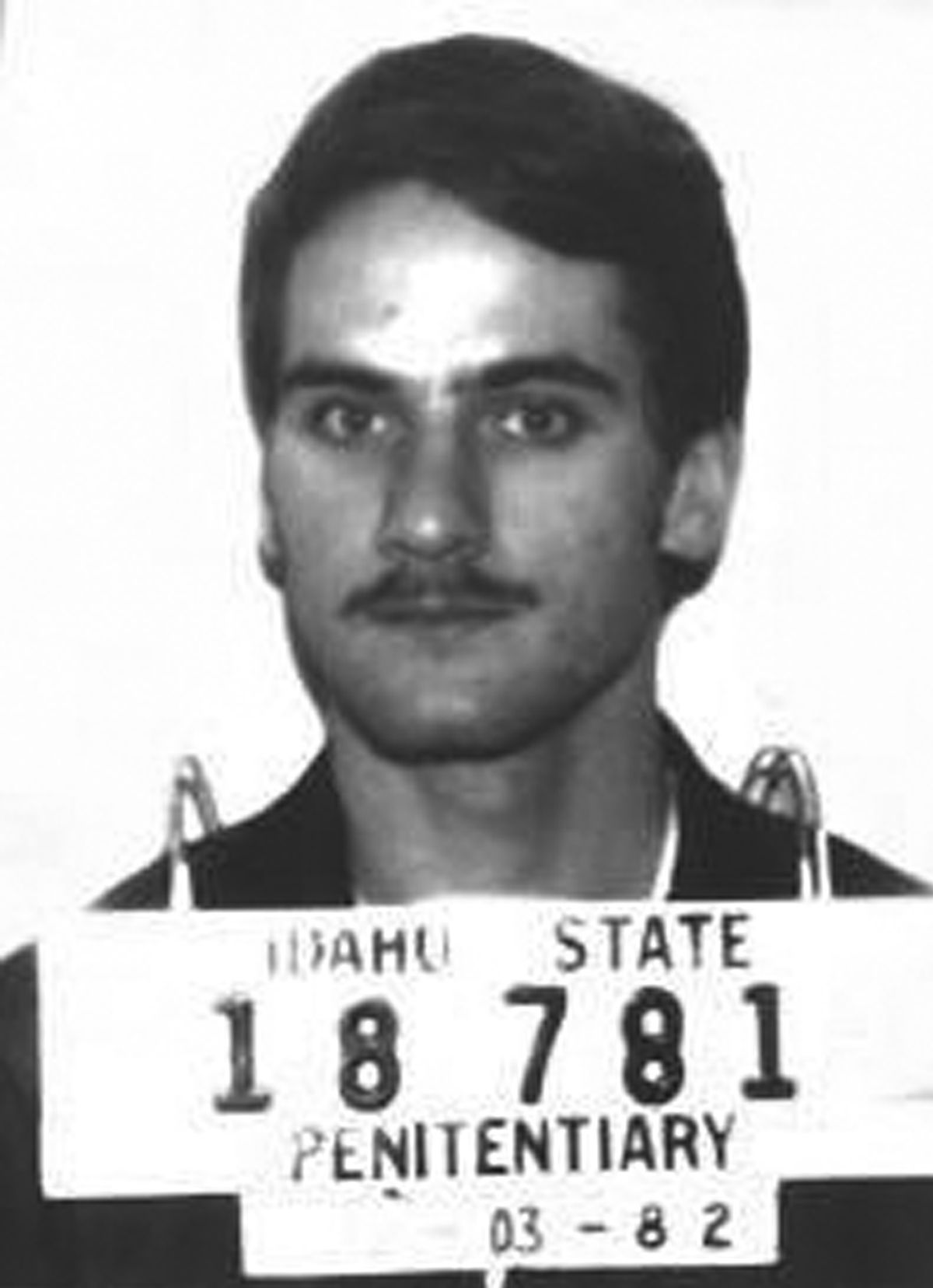

1982 Mark Brown arrives at the Idaho State Penitentiary at age 23.

It’s clear that Mark Brown is a smart guy, maybe even borderline brilliant.

But what’s astounding is the way he apparently pulled off a major, yearslong financial fraud, taking in big corporations, courts and attorneys across the nation, all from behind bars in an Idaho prison cell.

Brown had no access to the Internet and appears to have had no accomplices or outside help. Instead, investigators believe he used a cherished electric typewriter that he was allowed to keep in his small, spare cell, and legal ads found in national newspapers including the Wall Street Journal and USA Today, to make fraudulent claims in big class-action lawsuits and bankruptcies.

He’s alleged to have typed up professional-looking legal documents, false letters from law firms and more, and made skillful use of the “legal mail” exception for inmates that allows for correspondence with attorneys and judges without review from prison staff. Big checks poured in – Brown’s take in multiparty lawsuits including a $70 million GlaxoSmithKline drug-pricing settlement and a $20 million IBM shareholders’ settlement.

Authorities say Brown collected close to $64,000 through those settlements and deposited the money in his prison trust account, which inmates can use for things like commissary purchases. He then transferred much of it out to an investment account that authorities have targeted for potential forfeiture.

The discovery and subsequent investigation caught authorities by surprise.

“We screen our mail pretty well, but he also was running a pretty good scam here,” said Cpl. Wesley Heckathorn, a guard at the Idaho Correctional Institution in Orofino and former longtime U.S. Navy investigator who helped uncover Brown’s alleged fraud.

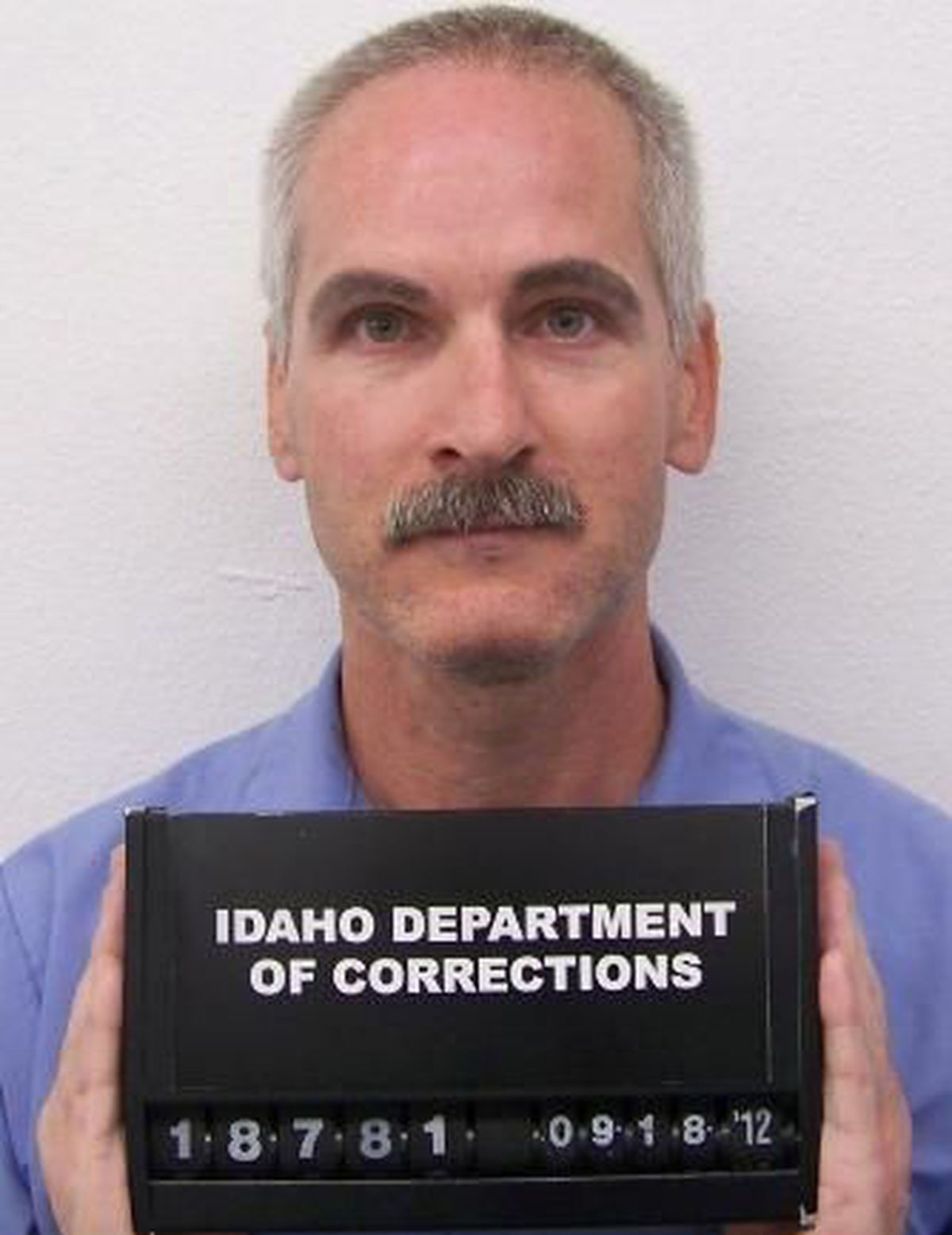

Brown is now facing a 12-count federal indictment for mail fraud and awaiting a September trial, while authorities at both Idaho’s state prison system and the nation’s largest private prison operator, Corrections Corp. of America, scratch their heads over how he allegedly pulled it off.

Some who know Brown, however, aren’t surprised.

“Mark is just so bright,” said Terry Rich, who hired Brown in 1994, when Brown was briefly out on parole, to work at his Boise high-tech firm. “He is so slippery, and he’s so believable, one of the most charming people you’ll meet. … If you let Mark sit around and think too much, this is what happens.”

Jeff Brudie, a 2nd District judge who, as a young lawyer, represented Brown in two of his early criminal appeals in the 1980s, said, “He is a smart son of a gun.”

The story of how Brown went from 23-year-old University of Idaho computer science student to 53-year-old inmate suspected of perpetrating one of the most inventive prison scams ever discovered is a tale of habitual crime, long sentences, mental illness and lack of treatment.

Sixty known thefts

Mark Anthony Brown’s criminal record stretches far back into his childhood, when he was in and out of juvenile detention for stealing. Before he’d turned 18, he’d committed 13 burglaries, according to court documents, including one at a U.S. post office. He faced other struggles, including a suicide attempt, an escape from a juvenile detention center and temporary placement in a foster home. By 1982, he’d been involved in 60 known thefts and burglaries.

He enrolled at the University of Idaho in the spring of 1978 to work toward a computer science degree and excelled there. But at night, he broke into university buildings, homes and businesses, hiding away his loot.

He was on felony probation in 1982 when a search of his university dorm room turned up piles of stolen property, from computer components and other electronics to jewelry. A search of his room at his grandparents’ home in Lewiston and his safe deposit box yielded more, including distinctive items like a Rolex watch, paintings and an engraved pen and pencil set. Brown was tied to dozens of burglaries in Moscow and Lewiston.

Brown was diagnosed with kleptomania and borderline personality disorder. In a 20-minute, tearful statement to the court, he pleaded for leniency as the judge pondered a 20-year prison sentence.

“I’m not saying I don’t need to be locked up,” the young defendant told the court, as the Lewiston Tribune reported at the time. “If that’s what needs to be done to keep me from stealing, then that’s what I wish. At the same time, I feel I need something else. I honestly feel that the things I’ve done stem from things I was never in control of.”

The judge was unmoved, but Brown won a more favorable sentence on appeal.

Brown got out on parole in 1994, but by then, he was a 35-year-old with a long list of disciplinary violations in prison. He’d broken rules, stolen items and forged purchase orders at his job at Correctional Industries. He’d tampered with computers to change the driver’s license status of five other Correctional Industries employees. In 1986, he’d even tried to submit a false claim in the Dalkon Shield litigation in Virginia, claiming he had used one of the faulty intra-uterine birth-control devices for women.

Back on the streets in Boise after being paroled, Brown found work at Rich’s company, Applied Process Controls, doing technical support for industrial instrumentation controls. “He adapted very quickly to any circumstance you could put him in, whether it was a conference room of Idaho Power engineers, anything,” Rich recalled. “He was great on the phones.”

Then, a few months later, Rich got a call in the middle of the night from Boise police detectives. “They said, ‘Does Mark Brown work for you?’ and I said yes. And they said, ‘Well, not any longer, because he’s going back to prison.’ I said: ‘Back to prison?’ ”

Eight days after a state parole office in east Boise had been torched, silent alarms were tripped at another Department of Correction office in west Boise. Police found a broken window and an oily liquid spread across computers and other equipment; moments later, outside, Brown sped around the corner in his two-tone 1978 Volkswagen bus. Officers gave chase and cornered him in an alley behind a grocery store; in the bus were a baseball bat with fragments of glass on it, a gas can, gloves, a flashlight, and a puddle of the oily liquid.

Brown was arrested and his apartment searched; it was full of stolen property, including lots and lots of computer equipment, along with exotic birds in cages and other items that were tied to a string of business burglaries in Boise. He was sentenced to serve up to 116 years in prison.

“I went and visited him at the Ada County Jail before he went back to prison,” Rich said. “I said, ‘Mark, why would you do this? I trusted you, gave you a chance to really start your life over again – this is what you do?’ ”

Rich was looking at Brown through the glass in the jail’s visiting area; Brown was emotionless, he said. “He just sort of shook his head. He told me he was a career criminal. He told me, ‘This is what I do.’ ”

Setting the stage

It’s unclear exactly when Brown obtained the electric typewriter that investigators believe he used in the fraud scheme and carried with him from one prison to the next.

According to his federal indictment, Brown’s securities and bankruptcy fraud scheme started in September 2007. That was the same month he was transferred to the North Fork Correctional Facility in Sayre, Okla., a private prison run by Corrections Corp. of America, as Idaho shipped hundreds of inmates out of state due to crowding. Brown stayed there two years, before being returned to the CCA-run Idaho Correctional Center south of Boise.

On Aug. 28, 2009, a search of Brown’s cell at ICC turned up curious items: numerous typewritten letters from various nonexistent law firms “purporting to provide proof of Brown’s purchase of various stocks or interest in various settlements,” from IBM corporate securities litigation to NovaStar Financial Inc. securities litigation. One litigation settlement letter was on the back of a Department of Correction inmate resolution form.

CCA officials placed Brown in segregation for five days, reclassified him to medium security and notified the Ada County Sheriff’s Department that they had a case of apparent mail fraud by an inmate. He also lost commissary privileges for 45 days.

“When our investigator became aware of possible fraud attempts by this inmate, he notified the proper external authorities and held the inmate accountable through our own internal disciplinary process,” said Steve Owen, senior director for public affairs for CCA. “Through this cooperative effort, the inmate is now being prosecuted.”

However, the Idaho Department of Correction has no records that CCA notified it about the case, other than the disciplinary report following the search noting that the case was “going to be turned over to law enforcement for further prosecution.” The Ada County Sheriff’s Office confirmed under the Idaho Public Records Act that it received a report from CCA but declined to release it because of the pending federal court case. It found no other records related to the 2009 report.

Nearly two years later, on Oct. 31, 2011, Brown was transferred to the state prison in Orofino. He brought along his typewriter; officials there weren’t told of the alleged fraud.

Five months later, however, Heckathorn, the guard at Orofino and a former longtime U.S. Navy investigator, became suspicious.