Weight watching

Taking off pounds is just the start; for many, the more difficult part is keeping it off

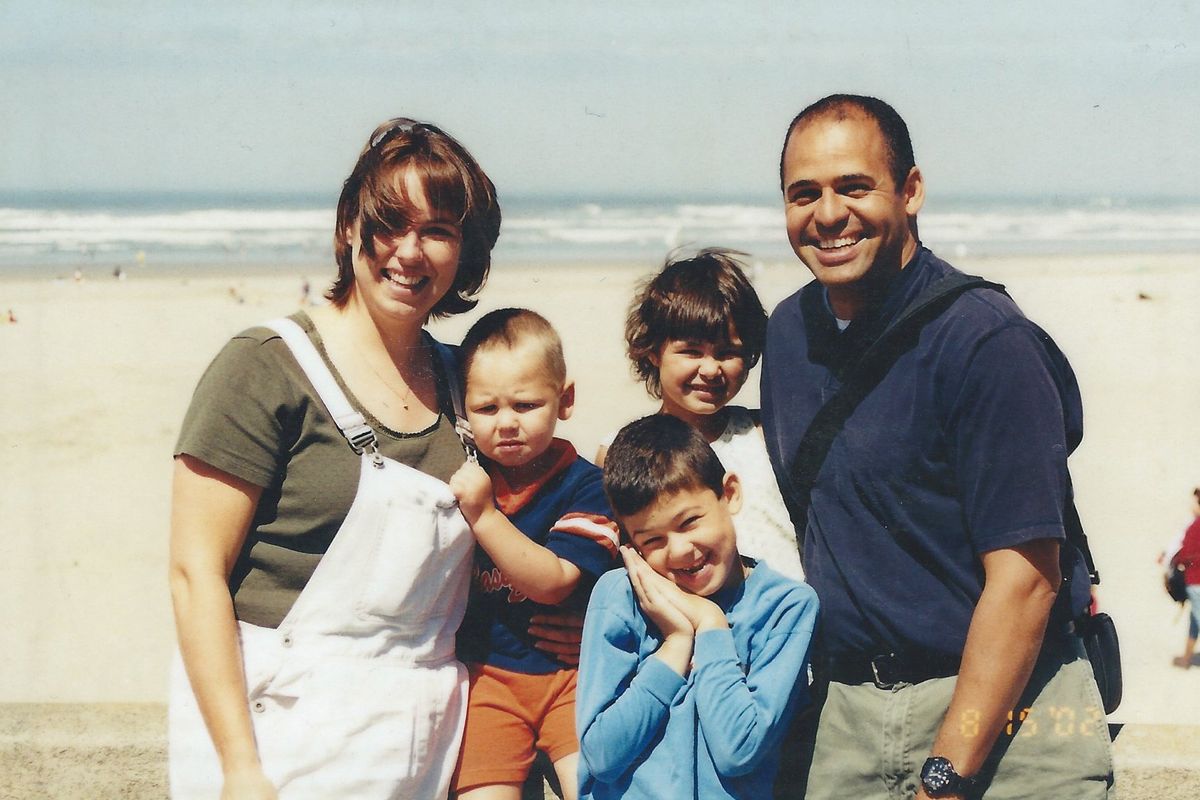

Cathy Goins, mother of three and longtime Weight Watchers leader, slices vegetables in her South Hill kitchen last week. (Jesse Tinsley)Buy a print of this photo

Losing weight is difficult enough. More difficult for many people: keeping it off.

Uncomfortable in her skin, unhappy with how she looked in photos, Cathy Goins joined Weight Watchers in 2003 and dropped 35 pounds.

She maintained her new weight for several years – until an eight-week stay in her home by a West African boy receiving medical care in Spokane turned into an eight-month stay. The orphan from Sierra Leone required more intense physical care-giving than any of her own three children ever did, she said. He’d fallen from a mango tree and never received medical care for his broken leg or jaw.

“The more I took care of him, the less I took care of myself,” she said.

Goins regained more than 20 pounds. After the boy, named Tejan, returned to Sierra Leone, Goins headed straight back to Weight Watchers. This time, after losing weight, she became a group leader to ensure she’d remain accountable to someone over the long haul.

Whether it’s because of stress, crowded schedules or an erosion of focus, most Americans who lose weight gain at least some of it back. Recent studies exploring the role of hormones in long-term weight-loss maintenance suggest our bodies are working against us: The hormone leptin tells our brains how much body fat we have; weight loss leads to less leptin, and our appetites grow. Other research on long-term weight loss explores the possible benefits of post-loss counseling, training in weight “stability skills,” and particular post-loss diets.

“There’s a different reason for each individual,” said Maddy Houghton, who teaches in Washington State University’s nutrition and exercise physiology program. “Everybody’s unique and different. But part of the problem is they see this as a very temporary effort, and a lot of times they have very unreasonable expectations. And a lot of times they go on very rigid diets that nobody – nobody – could succeed at for any length of time.”

A registered dietician, Houghton has worked in hospitals and as a weight-loss consultant, including recently at the Spokane Club. It’s often difficult for clients to hear that a two-week diet won’t do the trick – that long-term weight loss requires long-term changes.

“Even though they should know better, they don’t quite believe it until it happens to them,” Houghton said. “It hits them by surprise when their weight starts coming back on.”

But the long-term changes don’t have to be drastic, said Houghton and others who help achieve and maintain weight loss. In fact, small but sustainable behavioral changes are often more effective over the long term than severe ones, they said.

Goins said she has a guiding principle: “If I can’t do this for the rest of my life, I shouldn’t be doing it to lose weight.”

People who keep excess weight off for the long term have some behaviors in common, weight loss educators say. Among them, they:

• Eat a variety of foods. Even fats. Even carbs. “Any diet that is very restrictive and removes foods that you like from your diet is really hard to stick to,” Houghton said. While it’s possible to lose significant weight initially on a low-carb diet, for example, “Most people tend to fall off the wagon and think, ‘You know, I’d like to have a sandwich with bread or spaghetti with pasta.’ It’s hard to have a social life and go out and eat dinner with people and eat normal food. The people who succeed are the people who learn to eat normal foods, meaning bread and pasta … and just eat less of it.”

• Stay mindful of portion sizes. Choosemyplate.gov, a U.S. Department of Agriculture site, offers guidelines.

• Set goals that are reasonable, specific and “action-oriented.” If you don’t feel confident you’ll really exercise every day and lose 50 pounds, for example, scale back your ambition, suggested Jessie Stensgar, a health educator with the Spokane Tribe who works out of the David C. Wynecoop Memorial Clinic in Wellpinit, Wash. Instead of pledging to thin down by two dress sizes, decide what you’ll do to get there, along with when, where and for how long, Stensgar said.

• Set goals beyond a number. Many people lose focus after attaining a weight-loss goal measured in pounds, said Mindy Wallis, healthy living coordinator at the YMCA of the Inland Northwest. By focusing on what you gain from your new lifestyle – more energy, better sleep, less pain – you’re more likely to stay motivated to keep up your new behaviors.

• Record what they eat. “Food diaries” make diarists accountable for what goes into their mouths, even if they don’t show their journals to anyone. They also help prevent absent-minded eating.

• Don’t skip meals. Not even breakfast. People who skip meals lose control later, Houghton said, overeating from hunger while using the missed meal as justification.

• Tap into moral support. A spouse, a friend or a weight-loss group – someone to call when you feel tempted. Goins said the successful members of her Weight Watchers groups are the ones who keep coming to meetings even after they’ve met their goal weights.

• Keep exercising. “Some people are really intimidated by exercise, thinking they have to start running marathons or something,” Houghton said. “But really, those who’ve succeeded – they tend to exercise every day, but it can be walking, it can be gardening. It’s just moving every day.” Stensgar suggested scheduling exercise time in 10- or 15-minute increments that might be a walk around the neighborhood or up a few flights of steps at work. Shorter spurts are less intimidating than hour-long gym sessions, and if they’re on your schedule, they’re appointments that can’t be missed.

• Don’t give up after messing up. It’s a daily battle to make new behaviors stick, Stensgar said: “We have very addictive traits in our personalities. If we’ve been exposed to the sugars, the fats, it’s hard to let that go.” The secret is to get over it after a day of unhealthy eating or missed exercise. Start again the next day.

• Control their environments to reduce temptation. If she really wants some ice cream, Goins goes to an ice cream shop and gets a serving – rather than going to a grocery store for a gallon for the freezer. One of her children is a runner who requires lots of calorie-dense foods. His energy bars have their own cupboard. She steers clear of it.

She knows Weight Watchers members who make their spouses keep their unhealthy snacks in the trunks of their cars.

“Willpower can help,” Goins said. “But it runs out.”