Ducks Unlimited isn’t a hunting club; it’s all about wetlands, waterfowl

Chris Bonsignore relished popping up from a goose pit to bag three Canada geese during a morning hunt in a Columbia Basin wheat field.

In the afternoon, with his shotgun put away, Ducks Unlimited’s regional conservation manager beamed even brighter as he showed off DU’s partnership role in restoring nearby wetlands.

“This project will provide nesting and resting habitat to countless waterfowl forever,” he said, standing above hundreds of ducks and geese gathering on Sanctuary Lake in the Wallula Unit of the McNary National Wildlife Refuge.

Then, as though it were a staged Blue Angels flyover, strings of wood ducks began arriving from their feeding forays – flight after flight, setting their wings for the restored wetlands at Sanctuary Lake.

“My gosh, that’s about 500 woodies that just came over us,” Bonsignore said after a few quiet minutes peering through his binoculars. “Amazing.”

That’s DU in a nutshell, said Jason Rounsaville, who coordinates DU’s Northwest volunteers: “Our vision is more wetlands and waterfowl for everyone, and better hunting for waterfowlers.”

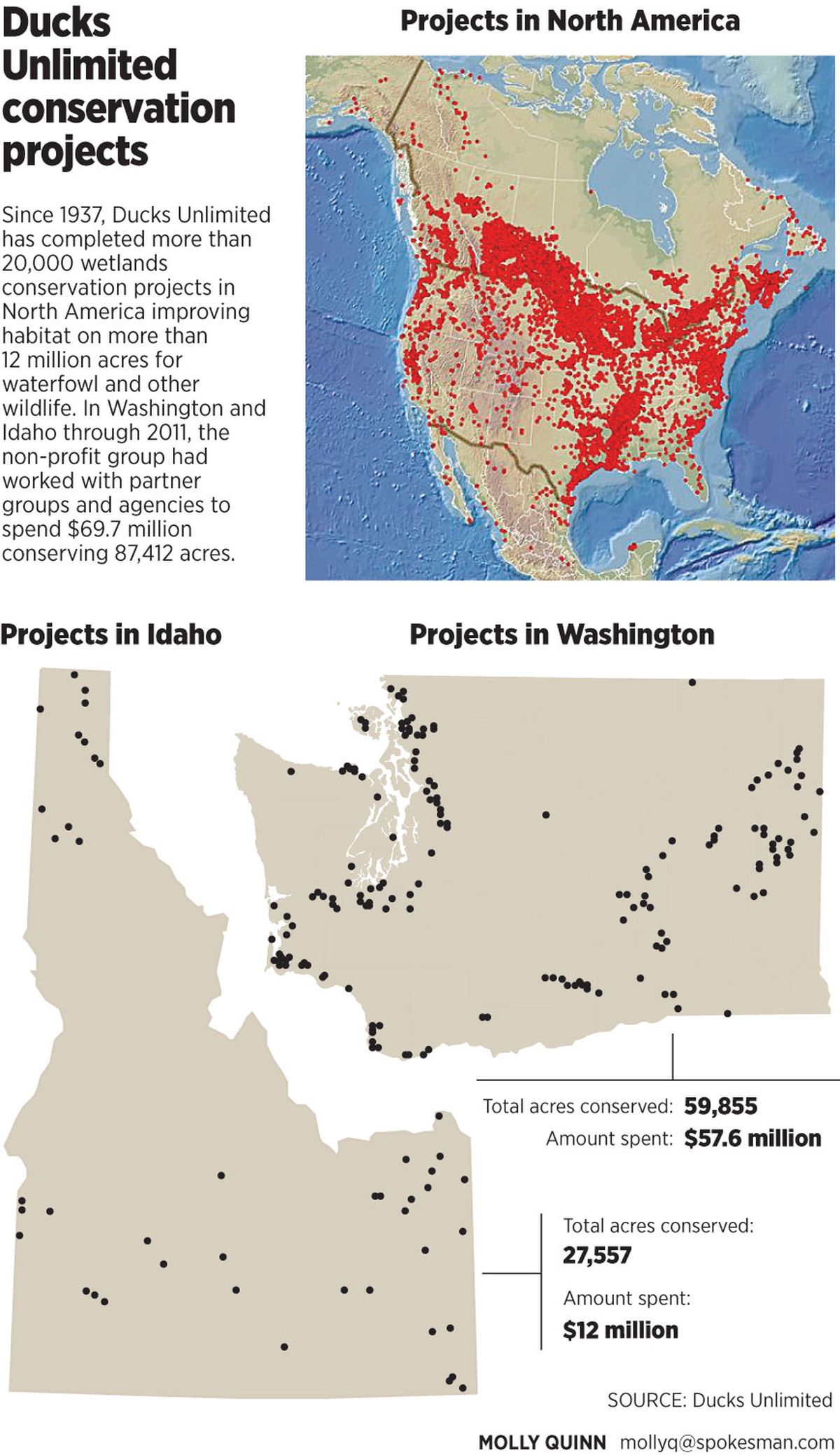

Founded in 1937 initially to preserve breeding areas for waterfowl, the wetlands conservation group has completed more than 20,000 projects in North America, conserving nearly 13 million acres.

But the battle is far from over, said Bonsignore, a wildlife biologist.

Although wetlands are incredibly productive habitat for a wide range of wildlife, millions of acres have been drained for agriculture or development, leaving waterfowl high and dry in many areas of North America, he said.

“Hunters will always be the core of DU because they have the passion for waterfowl,” Rounsaville said. “But when we get word out about what we do, people are impressed, hunters and nonhunters alike.”

DU has 2,800 chapters across North America. In fiscal 2012, about 45,000 volunteers organized 3,900 DU events that raised about $50 million for wetlands conservation, said Amy Batson, fundraising operations director at DU’s Memphis headquarters.

Fundraisers include golf, fishing and shooting events, as well as the traditional banquets and auctions, such as the one scheduled in Spokane Valley next month.

Most DU members are 48-52 years old with a core group of volunteers that donate at least 50,000 hours of time to projects a year in Washington alone, Rounsaville said.

While philanthropic watchdogs give DU average marks for its fundraising-related expenses, the group gets high marks for getting things done on the ground with only about 3 percent of the fundraising proceeds used for administration.

The key to DU’s success is leveraging the money it raises – as much as 20-to-1– with volunteer hours, grants and partnerships with other groups and local, state and federal agencies, Rounsaville said.

“DU has always had a continent-wide plan,” said Mond Warren, volunteer coordinator for Idaho. “That’s the nature of ducks: 85-95 percent of birds a hunter takes are produced somewhere else.”

Nevertheless, DU has been involved in more projects in local areas than most hunters realize, Rounsaville said.

“We’re criticized by some people for restoring wetlands on private land or public land where hunting isn’t allowed,” he said. “Our projects are science-based. We focus on the areas where we can get the most ducks for our bucks, regardless of whether it’s public or private land. More wetlands are better for everyone.”

Examples of current DU projects in the Inland Northwest include:

• Clark Fork Delta – A massive project to rebuild and stabilize islands eroded by operations of Albeni Falls Dam will be funded by as much as $8 million from the Bonneville Power Administration and Avista. Idaho Fish and Game officials are enlisting the expertise of Ducks Unlimited engineers to design the project to get the best results for wildlife, including Lake Pend Oreille fish.

“This area is historically a major wintering area for upwards of 30,000 diving ducks,” Bonsignore said.

• Channeled Scablands – DU was awarded a $1 million grant last fall from a North American Wetlands Conservation Act program to initiate the third phase of wetland restoration in Channeled Scablands areas mostly in Spokane and Lincoln counties.

The grant was the product of 17 partners – ranging from the Audubon Society and Inland Northwest Land Trust to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – that brought along nearly $4.l million in funding or services.

Projects will acquire or enhance about 2,400 acres of critical wetland, riparian, and upland habitats mostly by restoring wetlands ditched and drained for agricultural use.

Previous phases of this project enhanced 13,515 acres of wetlands on private lands, Spokane County Conservation Futures lands, U.S. Bureau of Land Management areas and Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge.

Intact wetland basins of the scablands scoured by the Ice Age Floods rival or exceed the waterfowl-producing capability of the Prairie Pothole region, Bonsignore said. But most of the larger basins were drained in the 1930s and ’40s for livestock grazing.

“This is a prime area to put our effort and we’re already planning Phase 4,” he said.

While these and other efforts are under way on the ground, DU also has an office in Washington, D.C., that keeps wetlands on the agenda for federal agencies and Congressional legislation such as the North American Wetlands Conservation Act, the Land and Water Conservation Fund and the Farm Bill.

“These are tough times for the federal budget, but we get their ear when they see we get a four-to-one return on the dollars we get,” Rounsaville said.

“DU isn’t a hunting club. Its single mission is habitat for waterfowl, an effort that also benefits a lot of other wildlife species, people, water quality and even endangered salmon.”