Career Transitions helps older adults catch up with technology

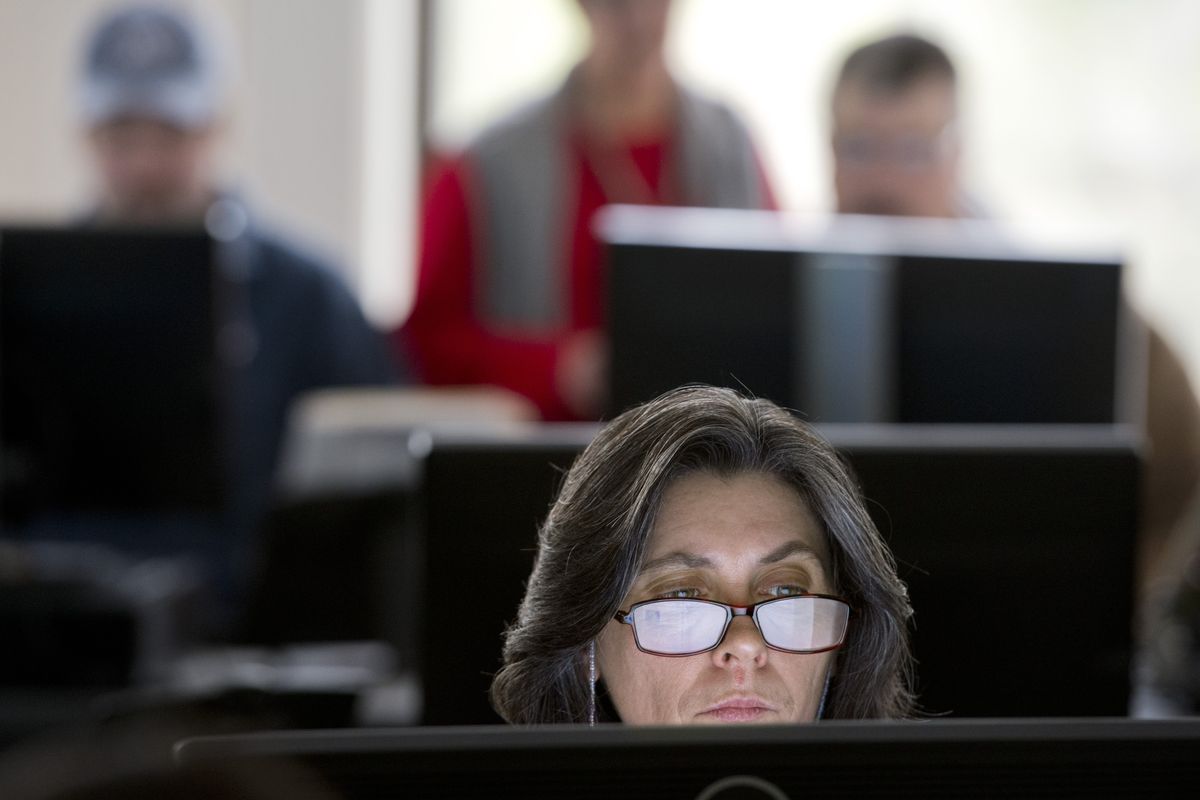

Jennifer Nevard, 49, participates in a Community Colleges of Spokane Institute for Extended Learning Microsoft Word training class on Jan. 31 at the Magnuson Building. Nevard says she has a bachelor's degree in lab medicine but has “no concept of technology.” (Dan Pelle)Buy a print of this photo

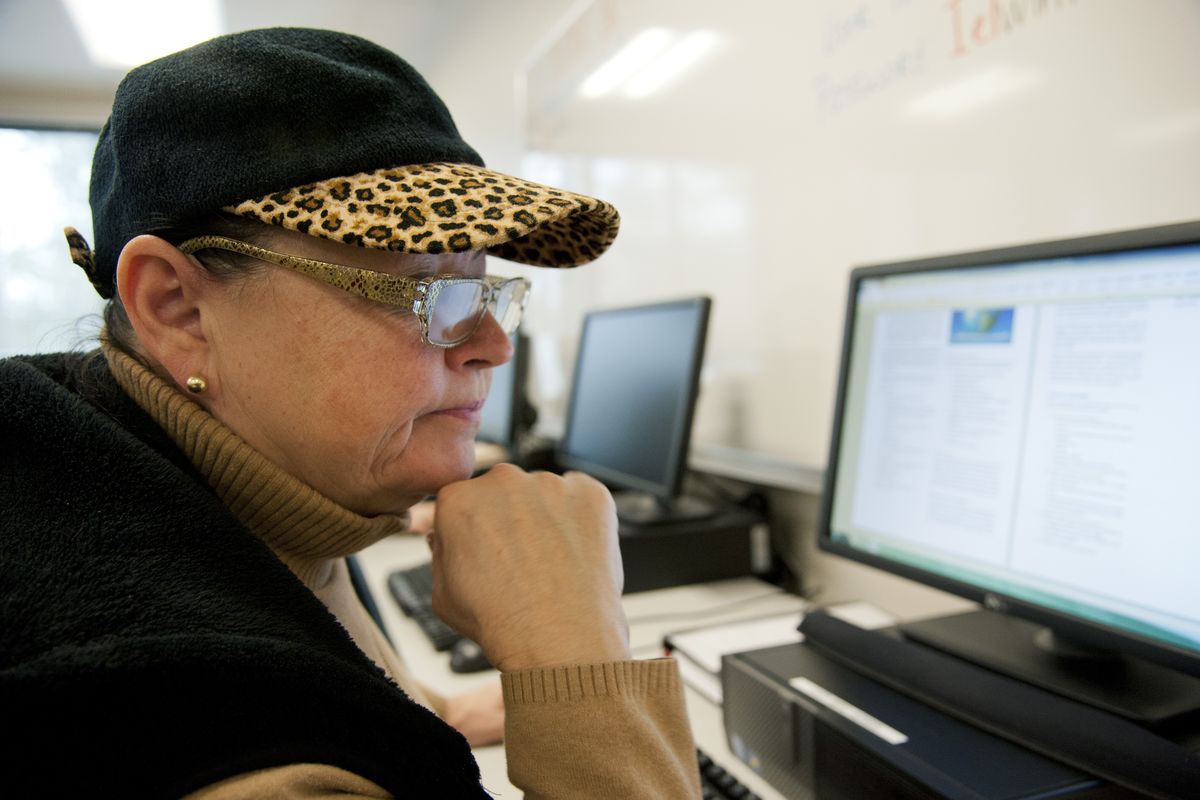

Mitzi Judd felt burned out after a long career in hair design, so she began working at golf courses. But at a golf course in Spokane’s climate, she said with a chuckle, “you get fired every fall.”

So now, at age 60, she is taking classes in the computer technology required to run her own business. She plans to open hair salons in active-living apartment complexes for older adults.

“I never thought I’d go back to my original career, but I’ve found a new love for it,” she said.

She’s taking her computer classes in the Career Transitions program at Community Colleges of Spokane. The program provides counseling and technical education aimed at getting people into the workforce.

The students, most of them older adults, need skills that did not exist when they attended school. Many have lost jobs. Some want new careers. A few want to finish a GED or enter college, but for one reason or another have never had a chance to make friends with a computer.

In your 50s and 60s, unemployment can be frightening indeed. Stock market crashes have savaged savings accounts, and joblessness drains them. A laid-off nurse’s aide, manufacturing worker or retail clerk may never have sat down at a computer to design a spreadsheet.

PowerPoint, Excel, Access, Windows 7, desktop publishing in Word, QuickBooks, business math, business writing, office teamwork and process analysis. It is a daunting list of skills that employers can demand or that launching a small business of your own might require.

Confronted with the demands of our high-technology world, the students at Career Transitions have come for help.

And they have come to the right place.

Rick Mudd, a jovial technology instructor who guides his students from paralysis to confidence, is accustomed to the fear.

“One lady literally spent the first week crying,” he recalled. “She didn’t think she could do it.”

All you need to do is show up, he told her. So she did. For moral support, she brought her sister.

Soon, both of them were on their way to becoming a master, rather than a victim, of the up-to-date PCs that fill the classroom and its adjoining computer lab, where students can practice on their own.

Whether the student is the victim of a layoff, or a longtime homemaker flung into the workforce by a family crisis, “most haven’t been in school in 30 to 40 years,” Mudd says. “They’re dealing with shock and grief and fear and the anxiety of having to learn something new.”

Mudd, who worked in the corporate world as a financial controller before changing careers to education, identifies with the challenges of learning late in life for a new line of work.

“What do I do for a living? I’m a cheerleader,” he said. “And the second thing I do is teach computer classes.”

Sami Salvatori, a dynamo who serves as the program’s counselor, administers tests that help students identify their interests and skills.

“Re-careering is scary for people, but it can be the coolest thing that ever happened,” Salvatori said.

She sought college degrees in her 30s.

“You can be educated later,” she said. “You might find a career that really suits you when you are older. I know the obstacles of older students, and I know the exhilaration of being an adult learner.”

Salvatori tells her students to begin with their goal – launching a small business, for example, or hiring on with a particular Spokane employer – and plan backward from there. She asks questions like these: What skills do you have? What skills do you need?

A student might be familiar with Microsoft Word but may never have used Excel.

When today’s older workers started out, desktop computers did not exist. But when layoffs hit and workers have to seek new jobs, they quickly discover that employers expect computer skills. In the construction industry, for example, plans take shape on computer screens and are delivered to the project superintendents by email.

On a recent winter day in Mudd’s classroom, the students included several women laid off by a local bank and a burly 66-year-old construction worker in a Harley-Davidson shirt.

Working their way through formatting drills in Microsoft Word, all intend to be ready the next time some job interviewer asks about technology.

If it’s been years since the last job search, it can be tough even to know where to start.

“We have a lot of students who don’t know what they want to learn, or what the options are,” Salvatori said.

She helps job seekers sort through lists of Spokane employers – most are small businesses – to identify those that seem like a good fit. “The goal here is to get you up to speed as quickly as possible.”

The students support one another. Mudd recalls a younger student so poor he had few clothes. Another student, in the same class, had retired after many years of running a Spokane clothing store, and supplied the clothes the younger student needed to make a good impression as he interviewed for jobs and embarked on a career.

Even though many of the students have emerged from the confidence-wrecking brutality of a layoff, as they work together to build new skills and lives, they discover a common bond.

“I tell students there are work environments like this – supportive, caring, positive.” And then, Salvatori helps her students find them.

Scott Morgan, acting president of Spokane Community College and CEO of the Institute for Extended Learning, which runs this program, underscores a point made by his instructors. To get back in the workforce, you don’t necessarily have to slog for years toward a traditional university degree, racking up a staggering student-loan debt.

Recently when U.S. News & World Report made a list of the 100 best jobs in the country, Morgan noticed that a third of those “best” jobs can be secured with a two-year community college education. The Career Transitions program, with its targeted counseling and six-week terms, offers a faster track.

Jenni Martin, dean of extended learning for the community colleges, notes that in addition to career-oriented classes, the community colleges operate the Act 2 program aimed at older, retired adults who want to update their computer skills for any reason: to communicate with grandchildren and friends, read the news, manage their health care or just keep the brain cells active and growing.

Dave Fender, who teaches Act 2 classes, recalled with a chuckle a student in his 90s who spent five days in a “computer kindergarten” class, and at the end was able to compose and send an email to his grandson.

Then he stood up, put on his coat, and explained that he probably would never touch one of those machines again. He had accomplished his goal. That one email made him happy.

Most students have more complex needs, such as rebuilding confidence, starting new careers. Those students, Salvatori said, “walk out of here feeling empowered.”

Pecking tenaciously away at the Microsoft Office skills she will need to launch that new beauty salon, Judd looks at it this way: “This program is a gift … and I’ve never had so much fun.”