Local civilian contractors among first American POWs in WWII

Their stories live on in a new book

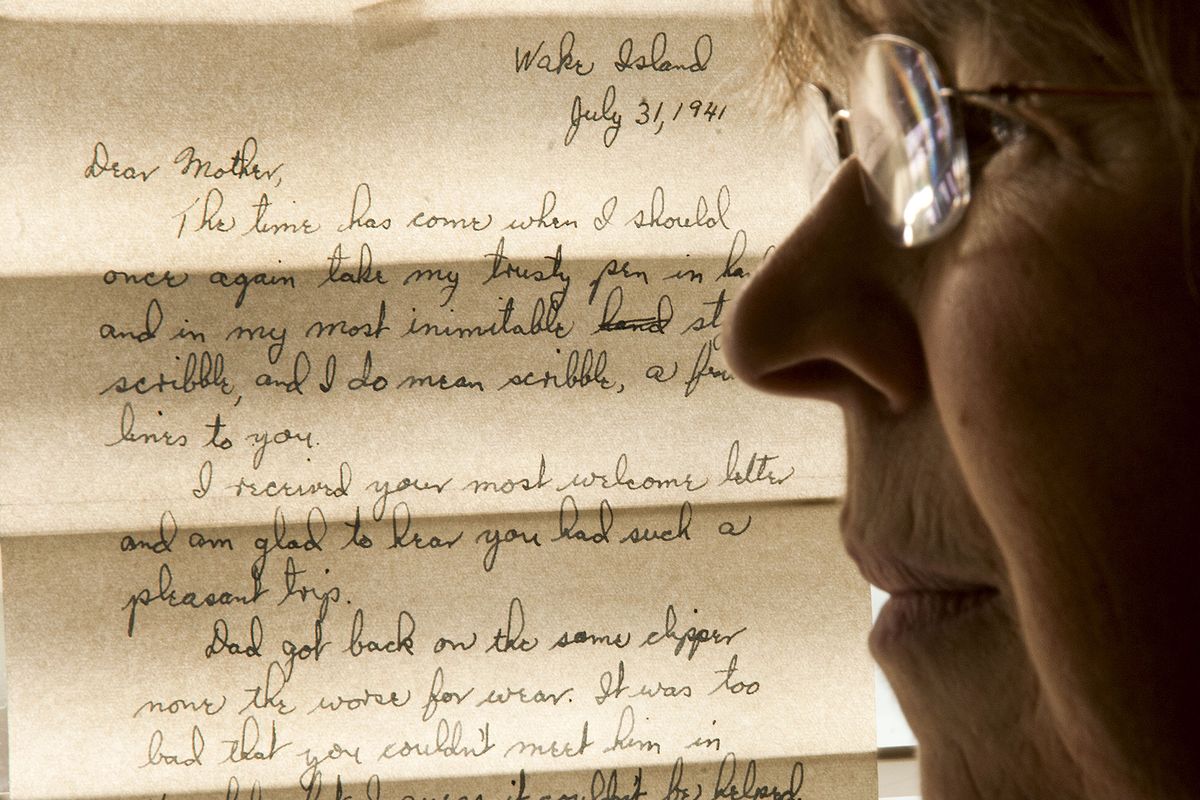

Bonnie Gilbert, of Coeur d’Alene, has written a book about Wake Island in World War II. Her father and grandfather were both civilian contractors on Wake Island, which played an important but little-known part in the war. (Kathy Plonka)Buy a print of this photo

After seven decades, Don Rumpel still gets choked up as he recalls his father’s internment in Japanese prison camps and his liberation at the end of World War II.

His father, Fred Rumpel, grew up on an Idaho farm and was among more than 1,000 civilian contractors taken prisoner in December 1941, when Japanese troops overran Wake Island.

Some of the civilian construction workers died defending the island, a U.S. naval air station in the Pacific Ocean, alongside U.S. Marines. Most of the survivors were split up among prison camps in occupied China and Japan, where they spent the war years as slave laborers. Many died of disease or starvation. Nearly 100 were massacred on the tiny atoll on which they were captured.

After 44 months in captivity, Rumpel and his fellow internees were incredulous when they were told the war was over, his son said recently.

“They had heard the rumor so many times, nobody took it seriously,” said Don Rumpel, 84, of Kellogg, who was in the eighth grade when he learned his father would be coming home at last.

A new book, “Building for War: The Epic Saga of the Civilian Contractors and Marines of Wake Island in World War II,” tells the story of the race to build naval and air bases on the island at the brink of war with Japan.

The book is a labor of love for Coeur d’Alene author Bonita “Bonnie” Gilbert, who teaches history at North Idaho College. Her father, Ted Olson, and grandfather, Harry Olson, both were on Wake.

Inland Northwest connection

Like many of the 1,145 civilian contractors on the island, the Olsons were from the Northwest. The men were employed by Contractors Pacific Naval Air Bases, a consortium of large construction companies, including the Morrison-Knudsen Co. of Boise, which recruited laborers from the region. In winter 1941 the nation was still in the midst of the Depression, and good-paying jobs were scarce.

Besides Wake Island, the Hawaii-based consortium was involved in military construction on Midway, Johnson and Palmyra atolls and on Guam.

About 240 of the civilian workers on Wake were from Idaho, including five from the Coeur d’Alene area, according to Gilbert’s research. About 120 were from Oregon, and 70 from Washington, including 10 from Spokane. About a dozen men were recruited from the mining operations at Metaline Falls, Wash., because of their experience using explosives for blasting.

In addition to the civilian workers, there were 524 military personnel stationed on the island in December 1941, including 449 Marines, according to Gilbert.

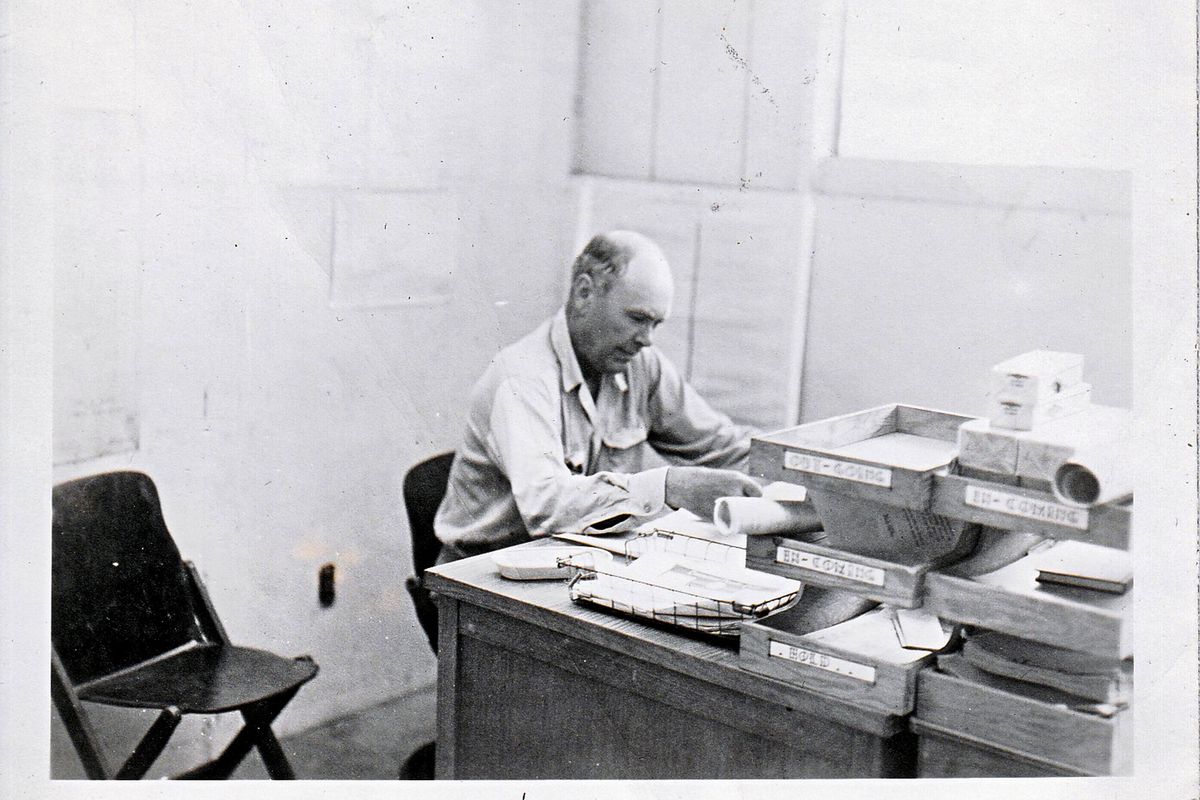

Harry Olson, then 46, was hired away from his work on the nearly completed Grand Coulee Dam to become the assistant general superintendent for the Navy’s air station project on Wake. The Portland native arrived in January 1941 to help prepare the island for the workers to come later, including his son Ted, a 22-year-old steelworker.

On Dec. 4, 1941, Harry Olson, ready for a vacation, flew a Pan Am clipper to Pearl Harbor, arriving in time to witness the Japanese attack on Dec. 7. He was immediately called to help with rescue and recovery operations in the aftermath.

Hours after the attack on Hawaii, Japanese forces launched an assault on Wake Island. The civilian workers aided the Marines in the defense of the island, but after a two-week battle, Wake fell to the enemy.

1,200 Americans taken prisoner

Gilbert said 92 U.S. military and civilian defenders were killed in the battle. About 1,200 Americans, including Gilbert’s father, were taken on the ship Nitta Maru to prisoner of war camps in Japanese-occupied China.

Some civilian workers were left on Wake as slave laborers. On Oct. 5, 1943, after a U.S. air raid, the Japanese executed the remaining 98 prisoners on the island, including several from the Inland Northwest.

Only 895 of the civilian workers on Wake at the time of the Japanese invasion returned home in the fall of 1945. Ted Olson was among them. He had been taken to Japan, where he was forced to work in the Yawata Steel Works on Kyushu until he was liberated in September 1945.

“He had lost a lot of weight in camp and he suffered from recurring diseases, including malaria,” Gilbert said. “Some of the men came back missing limbs or in terrible shape. One died in San Francisco harbor.”

Ted Olson came home to Portland, where his mother threw a party for him. It was at the party that he met his future wife, Dorothy, with whom he had three children, including Bonnie Gilbert. He died in 1994.

Harry Olson worked at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation and for Morrison-Knudsen. He died in 1968.

Wake survivor groups met for years

Like Gilbert’s father, many of the Wake survivors were reticent with their families about their wartime experiences. But they met for years in groups like the Spokane chapter of the American Ex-Prisoners of War or the Survivors of Wake, Guam and Cavite.

Gilbert’s research began with documents, letters and newspaper clippings gathered by her grandmother. She also met a number of the survivors, some of whom knew her father.

“The story reveals quite a bit about why our nation was taken by surprise on Dec. 7, 1941,” Gilbert said.

“The disconnect between the Navy and the contractors was debilitating to the war effort,” she said. “There was an awful lot of red tape to get things built by government contract.”

And there was American hubris.

“Despite the fact that tensions were rising in the Pacific and war was looming on the horizon, there was this notion that American technological superiority would win out,” Gilbert said. “There was a prevailing sense of bigotry as well that diminished and demeaned this rising power in the western Pacific and just assumed that (Japan) would be incapable of taking on American might.”

During the war, efforts were made in Congress to address compensation for civilian workers who were captured.

The War Claims Act of 1948 provided civilian internees of Japan $60 for each month of internment, as well as compensation to families for disability or death. In 1981, the civilian prisoners of war also were provided veterans benefits, including health care.

Don Rumpel recalls his father telling him about some of the privations he and his fellow POWs suffered, including disease, starvation and beatings.

“I don’t think a lot of people realize how much those prisoners actually went through,” Rumpel said.

His father also told him that civilians would “smuggle food in under the barbed wire” to help the prisoners survive.

“He never had any hard feelings against the Japanese,” Rumpel said.