Glacier Peak Wilderness hikers find nature untamed near hidden volcano

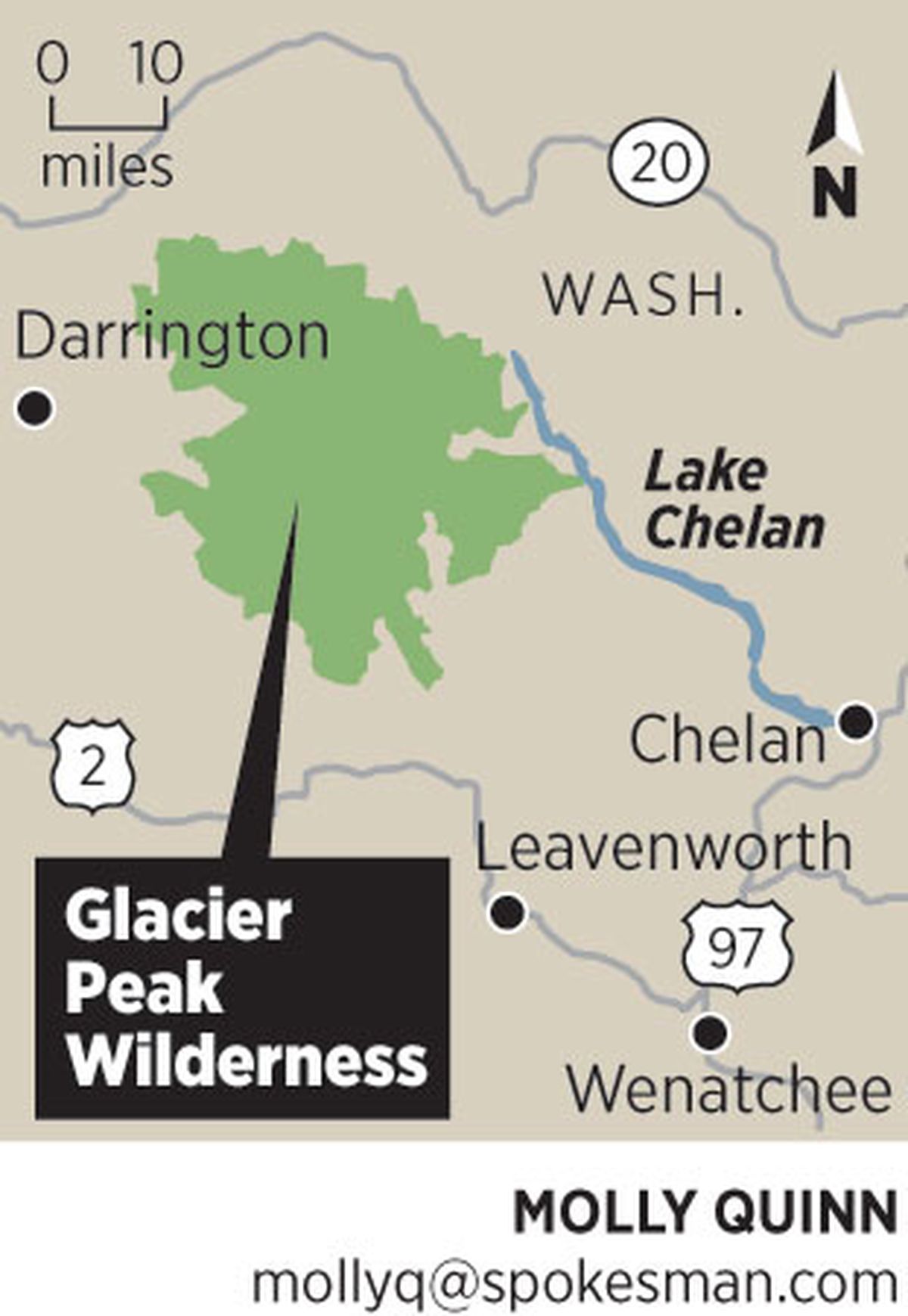

The Glacier Peak Wilderness, protected by Congress in 1964, covers 566,057 acres managed by the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forests and the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forests. The area includes Glacier Peak, 10,541 feet, a dormant volcano and the fourth highest mountain in Washington.

Holly Weiler was blunt in the Spokane Mountaineers calendar item about the August trip she was leading through the Glacier Peak Wilderness:

“We’re hiking a loop –Trinity Trailhead (near Lake Wenatchee) to Buck Creek Pass, out to Image Lake, back past Lyman Lakes, and up and over Spider Gap to Spider Meadows. It’s beautiful AND it’s tough. Participants must be capable of hiking 10+ miles a day with a fully loaded pack while going up (and down … and up again) over some tough mountain passes. Limited to six experienced backpackers. Bring the good camera equipment for this one! Also bring an ice axe for Spider Gap (and knowledge of how to use it).”

Adding to the challenge for participants was the high school English teacher’s annual Hike-a-Thon commitment to log as many trail miles as possible for pledges benefiting Washington Trails Association projects.

“We’ll likely do about 50 miles in four days,” said Weiler, the University High School girls cross country team coach who practices the fitness she preaches: In July, she had only two no-mileage days on her running calendar.

The Glacier Peak Wilderness was made for people like Weiler.

The first day of the wilderness trek alone – with full packs up to Buck Creek Pass plus side trips to Flower Dome and Liberty Cap – would involve about 14 miles and roughly 4,000 feet of elevation gain.

Hikers signed up, but all bagged out as departure day neared except for Weiler, trip co-leader Samantha Journot, and me.

I detailed all of this the day we left to my physician wife, Meredith Heick, as I followed normal procedure in our household by writing down the trip itinerary and agency emergency contacts.

I noted that the average age of my two companions is 30 – half my age.

“Here Honey, carry this in your pocket,” Meredith said after returning from the medicine cabinet with a small zipper bag. “Two aspirin – if you have chest pain, crush and put them between your lip and gum. It could save your life.”

Visiting the 566,430-acre Glacier Peak Wilderness, and especially its namesake mountain, is a remote experience no matter how you approach it.

Glacier Peak, elevation 10,541 feet is the fourth-highest mountain in Washington and the most remote of the state’s five active volcanoes.

By the 1790s, Mounts Baker, Rainier and St. Helens were noted and named in the first written descriptions of the Columbia River and Puget Sound regions. Mount Adams was noted by the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805 and named in the 1830s. But Glacier Peak did not appear on a published map under its current name until 1898, says the U.S. Geological Survey website detailing its volcanic history.

“(Glacier Peak) is not prominently visible from any major population center, and so its attractions, as well as its hazards, tend to be overlooked,” USGS says.

The area’s remote, famously rugged and diverse landscape was designated a wilderness by the U.S. Forest Service in 1960, four years before Congress secured its protected status in the Wilderness Act.

Today the Glacier Peak wilderness is sandwiched between the Henry M. Jackson, Wild Sky and Alpine Lakes wilderness areas to the south and the Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness and North Cascades National Park to the north.

Virtually any loop hike of more than three days in the wilderness will range through old-growth forest, alpine meadows, U-shaped glacial valleys and mountain cols over craggy ridges.

Huckleberries range from valley floors to as high as shrubs can be found.

Mosquitoes and black flies can be thick as fog on a calm day.

“I’ve been here before,” Weiler said as we drove to the trailhead northwest of Leavenworth. “I’m bringing a headnet.”

“Long pants are a good idea, too,” I suggested, pointing to the shorts she and Journot were wearing.

They laughed.

About 100 official trails in the wilderness total 450 miles, including a rugged 60-mile stretch of the Pacific Crest Trail.

The official trails include lofty cliff-hangers and leg-numbing fords of glacial streams. Additional miles of unofficial cross-country hiking and climbing routes rise to higher levels of difficulty as they angle above treeline, crossing snowfields, talus and scree.

The Ptarmigan Traverse, the most fabled untrailed route, combines rock climbing and glacier travel across 15 miles of the northern section of the wilderness.

The Glacier Peak Wilderness has more active glaciers than any other place in the lower 48 states, according to the Forest Service. Most of the year-round ice is on Glacier Peak but also on about a dozen other peaks in the wilderness.

More than 200 lakes dot the high country, most of them unnamed and rarely visited in untrailed cirques and basins.

The Spokane Mountaineers’ trek required a mixture of on- and off-trail routes facilitated by some remarkable Forest Service trail engineering. Inconspicuous culverts and berms constructed by crews on the most popular routes allow hikers and horses to cross the countless creeks and bogs of the North Cascades without breaking stride.

We noticed the rock work, such as the steps up Cloudy Pass, and the number of logs cut out from avalanche paths and the girth of the old-growth spruce and hemlock blowdowns that had been sawed off the lower forest trails – all with cross-cut saws.

Chainsaws and other motorized equipment are not allowed in the wilderness, even for the crews from the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forests, which co-manage the wilderness with the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest.

That doesn’t mean the wilderness is always peaceful and quiet.

Since the end of the last Ice Age, Glacier Peak has produced some of the largest and most explosive eruptions in the state. The most recent activity involved relatively small steam eruptions about 300 years ago.

SGS experts say Washington residents aren’t likely to witness a Glacier Peak eruption in their lifetimes, although the chance of significant activity is one in a thousand in any given year.

But another sort of fiery activity raged in the wilderness last weekend.

On Friday night, after a full-day of hiking and well-deserved huge meals cooked on our camp stoves, Weiler, Journot and I were admiring the stars in the clear night sky above our Buck Creek Pass campsite.

A “shooting star” blazed a long orange trail seemingly right over our heads, reminding us that the Perseid meteor showers were kicking into gear.

Clouds were building beyond the ridges around us. Bursts of light danced around the darkening skies, followed by muffled booms that gradually got louder.

The intensity of the thunderstorms closed in at midnight and again at 4 a.m. with the shock and awe of the bombing of Baghdad.

We’d camped in a basin, protected from the wind and rain by small trees but far from the largest and highest trees in the area, but the storm at one point zeroed in on us as though our tents were a target.

I put my hands over my ears. Blinding flash left me seeing a greenish yellow spot wherever I looked. My ears rang.

“Where in the hell’s that aspirin,” I thought, searching my pockets.

We survived, dried out the next morning and continued our trek, passing several groups of hikers that were bailing out of the wilderness after enduring wet, terrifying evenings. They had camped in exposed high-elevation sites to enjoy the view and avoid some of the bugs, but they paid a price.

“Wind blew my tent down on my face and the lighting was bouncing off the walls around us,” one guy said. “It was horrible.”

Weiler shrugged as they left, and began swatting black flies biting her legs. Journot started slapping to, even though she’d found some relief by spreading mud on her exposed skin. The slapping picked up to a frenzy that sounded like the clapping sequence in “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.”

Black fly carcasses piled up at their feet.

“Pants are good,” I said standing by calmly as fly carcasses piled up at their feet.

Our group hiked to Image Lake just in time to hunker down for another evening series of thunderstorms spreading from the lake’s iconic view of Glacier Peak.

This time the first deafening thunderstorm pounded us with hail. Rain followed, flushing piles of hail off the slopes and into rivers of ice balls flooding down the slopes like glaciers in fast motion.

Piles of hail remained 12 hours later as we dried gear in the morning sun. Huckleberry leaves littered the trail like holiday confetti on New York Streets. A mouse lay motionless near camp apparently stoned to death by the storm.

Lightning maps monitored by the Forest Service showed more than 7,400 strikes occurred from 9 a.m. Saturday until 9 a.m. Sunday along the eastern slope of the Cascade Range and in Southeastern Washington, including the Glacier Peak Wilderness where we were hunkered a day or two from any road.

On the third day we virtually had to run down off Cloudy Pass to Lyman Lake to beat yet another building thunderstorm.

But this storm cleared before sunset. Our next-day’s snowfield route through Spider Gap looked welcoming. Wilderness seemed peaceful again; although we later learned intense storms farther north had closed the North Cascades Highway with mudslides.

“You have to take it as it comes out here (in the wilderness),” Weiler said, returning after sunset from a post-storm hike above treeline to Upper Lyman Lake.