Famous architect’s legacy on display daily in home town

The exterior of the studio side of the Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio in Oak Park, Ill., which was built in 1889 as Wright’s family home and went through several renovations through 1898. This is where the famous architect developed Prairie style architecture.

OAK PARK, Ill. – Ernest Hemingway was born in Oak Park, but Frank Lloyd Wright lives here.

Wright died in 1959, two years before Hemingway, but the famous architect’s legacy is so strong in this village west of Chicago that he seems to be part of the present. Home to more than two dozen Wright structures, including a church, two stables and a fountain, Oak Park boasts the largest collection of Wright-designed sites in the world. Wright lived in Oak Park for the first 20 years of his career, between 1889 and 1909, developing Prairie style architecture in a studio there. In contrast, Hemingway couldn’t wait to leave, reportedly disparaging it as a place of “wide lawns and narrow minds.” (The future novelist left at age 18 to become a reporter for the Kansas City Star.)

Some 80,000 people tour Wright’s Oak Park home and studio each year (and about 10,000 visit the Hemingway sites) but visitors can also get a sense of Wright’s impact just by strolling up and down the streets. This village of 52,000 is a living testament to his influence.

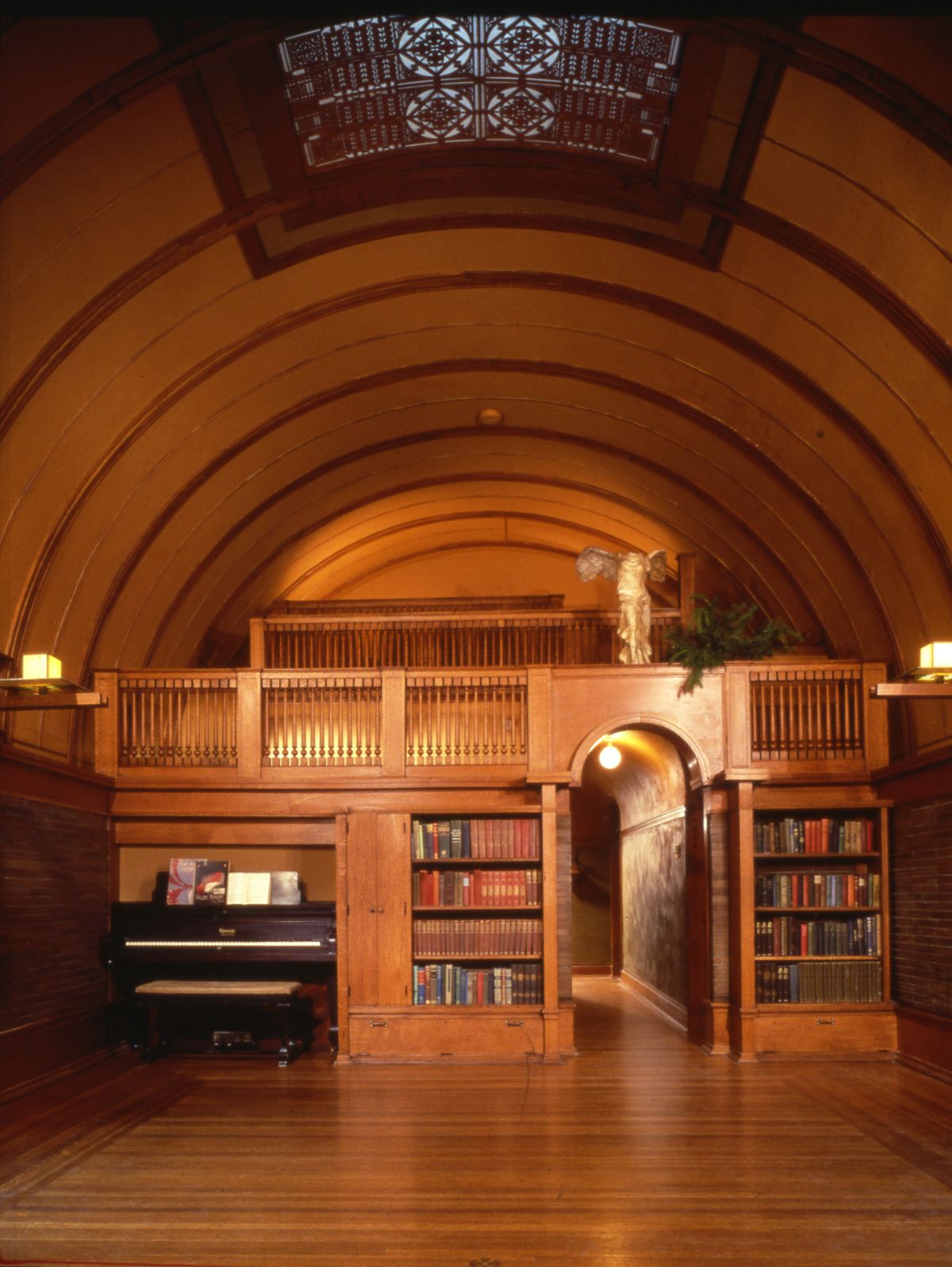

That’s part of why visiting Wright’s home and studio is such a treat: A chance to see where the person responsible for it all lived, worked and created. “This is like a creative lab,” said Tim Samuelson, Chicago’s cultural historian and a member of the advisory board of the Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust.

As guides lead visitors through the house, often past furniture that Wright built, they explain Wright’s use of space: How he not only controlled room size, which every architect does, but also influenced how big or small the rooms felt to people inside them.

Then there’s Wright’s attention to what occupies all that space: Light.

“Whenever he got a job he’d look at the site and see how the light fell” at different times of day, Samuelson said.

And while Wright didn’t spend a lot of time consulting clients about where this wall or that room would go, he did have a sense of what they would like.

“He had happy first clients, the houses fit them like a glove,” Samuelson said. Of course, someone as eccentric as Wright, who famously strode about with a cape over his shoulders and a cane in his hand, tended to attract clients who appreciated Wright’s sensibilities.

Wright also understood that the automobile wasn’t a passing fad and that he’d better design his houses to cope with shining headlights and noisy engines.

Listen, the tour guide says, pointing to one of Oak Park’s busiest streets, just outside Wright’s window. The columns outside are not just decorative; they absorb noise, rendering near-silence.

But what really makes a tour of Wright’s home and community fun is that it brings a man who has been dead for more than a half century back to life as a neighbor, businessman, father and husband, without whitewashing his flaws.

For example, he liked the finer things in life but often strung merchants along when they came after him for payment.

Wright also got tongues wagging when he ran off with the wife of another client, leaving his wife and kids in his house and his mother in the house next door.

Maybe the best story about how Wright’s work and personality came together is the one told at the end of the house tour in what was his office.

Wright’s houses tended to have leaky roofs, at least partly because Wright asked contractors to build houses unlike anything they’d built or even seen before. But Wright didn’t seem much bothered by it, whether the owners blamed him or not. When people would call to complain, “There’s water leaking on my desk,” Wright, as the story goes, would simply advise them to move the desk.