Former WSU star’s disappearance was 25-year mystery

It’s probably the biggest sports-legend mystery ever to come out of Washington State University.

Whatever happened to Dale “The Whale” Ford?

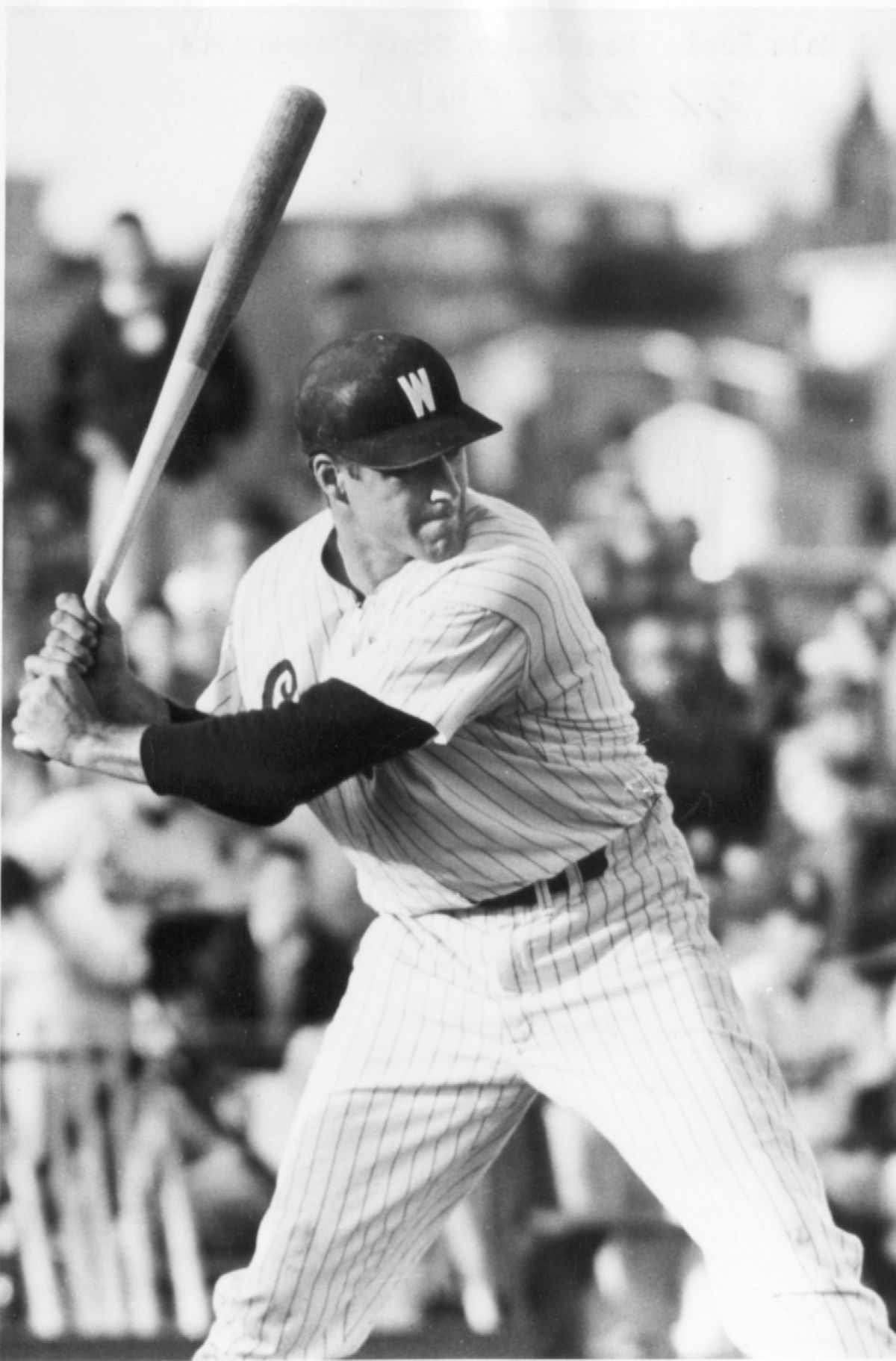

Almost 50 years ago, Ford was a standout outfielder for the WSU baseball team, known for his killer home runs. He also was a quarterback for the Cougars and played basketball – a rare three-letter athlete who set records still standing at the school.

His name is still well-remembered by aging coaches; his photograph still shines in the WSU Athletic Hall of Fame on the Pullman campus.

His athletic accomplishments at WSU launched a two-year professional baseball career, but it was cut short by knee problems. Suddenly, Ford no longer was living under the heat lamp of sports notoriety that he’d known his whole life.

He moved back to Washington and married a woman he’d met at WSU. They had two daughters and lived in the Seattle area. Dale Ford dreamed of becoming a rich man in the world of real estate before things soured and his wife divorced him.

Then, for reasons no one still fully understands, William Dale Ford simply disappeared.

His disappearance caused sports junkies and fellow athletes to ponder the fate of the WSU sports star.

Is he dead or living homeless somewhere? No one knew for sure.

Even a private investigation firm hired to find Ford couldn’t positively determine his whereabouts after a yearlong investigation.

His two daughters, brother, sister, ex-wife and 90-year-old mother were left without clues.

Ford’s mother hasn’t heard from her eldest son since 1987. Worried and heartsick, she and her other son, Tim Ford, finally went to the Seattle Police Department in 1991 and filled out a missing person report. They even turned over Dale Ford’s dental records in case, as Tim Ford explains, “he ended up as an unidentified ‘John Doe’ in the morgue.”

That hasn’t happened and the family lived without answers – until a few days ago.

Copies of Ford’s missing person report, obtained from the Seattle Police Department earlier this year after three public records requests, finally turned up a hint to his whereabouts – he was arrested in Santa Barbara, Calif., in 2007.

But the Seattle Police Department, honoring Ford’s request, didn’t tell his family of the arrest.

Those public records show Ford was arrested on Sept. 22, 2007, for drinking a beer on school property, near an athletic field just outside a Grateful Dead outdoor concert, and lying about his true identity to the arresting officer.

As he was booked into jail and fingerprinted, Ford admitted who he was and gave the arresting officer an office address on State Street in Santa Barbara. That location housed an upscale restaurant and office suites at the time, and no residences. The property manager and other tenants said they don’t know a William or Dale Ford, nor did they recognize his 2007 jail booking photo.

When contacted a few weeks ago, the arresting officer, Mark Suarez, now retired from the Santa Barbara Police Department, said he believes Ford likely was homeless, staying in various shelters in Southern California.

Other addresses used by Ford obtained from various databases led to empty strip mall offices. One even listed a Teamsters Local office in San Diego where the office manager checked and said Ford was not a current or former Teamster.

After being arrested outside the Grateful Dead concert five years ago, Ford appeared to vanish again.

Records suggest he remembers the daughters he hasn’t seen in a quarter century – he used their first names of Samantha and Danielle to create the alias of “Sam Dan Holding” while living in the homeless shadows of Southern California.

The man who once swung a mighty baseball bat for WSU also befriended and got some financial support from a conductor who swings an orchestra baton far from the Palouse.

Even police can’t find Dale Ford to serve a bench warrant for his arrest, issued when he failed to show up in court in October 2007 on the two misdemeanor charges. His Social Security number hasn’t been entered in the agency’s death index and there’s nothing to suggest he’s deceased.

“I’m afraid it’s just a tragic story with an unhappy ending,’’ said Ford’s ex-wife, Pam Spoo, herself a WSU graduate.

Parental support in early years

William Dale Ford was born on Nov. 9, 1942, in Ellensburg to William and Dorothy Ford. The couple later had another son, Tim, born in 1945, and a daughter, Susan, born in 1947.

The family lived a couple of years in Spokane before moving to Ephrata in 1945 and back to Ellensburg a decade later. His father was a supervisor of game farms for the state of Washington and ended his career at the state wildlife office headquarters in Olympia while the family lived in nearby Lacey.

The elder Ford, himself a high school track standout in Yakima and Ellensburg, was keenly interested in his sons’ involvement in sports and regularly attended their high school games, Tim Ford recalls.

“In all honesty, we always had two sets of coaches,’’ Tim Ford said. “We had the coach on the field, but then when we got home, we went through this process all over again with my father. Dale took criticism and direction much better than I did.”

“The one thing that Dale and I could always count on is knowing that our parents were sitting in the bleachers,” Tim Ford said.

Once Dale became a Cougar, his father and mother would regularly visit Pullman and drive to WSU road games in Oregon, California and Seattle.

At WSU, Dale initially lived in Kreugel Hall before moving into off-campus housing with fellow jocks John Olerud, Danny Frisella, Jim Hannah, Roger Merritt and Dale Scilley, Tim Ford said.

As Tim joined the military in 1966, his brother signed to play pro baseball and was almost immediately traded to the Los Angeles Angels. He got a signing bonus and played with the Angels’ minor league farm team in Lodi, Calif., before going to the San Jose Bees in 1967.

He had a good year with the San Jose Bees and went to the Angels camp for spring training in early 1968, Tim Ford said. “But over the course of that winter, Dale’s legs gave out on him. Football, basketball and baseball are what happened. He had numerous operations on his knees in college.

“The doctors told him at the time he had the legs of a 65-year-old man, and Dale couldn’t have been 25, 26 years of age. So, basically, he was washed up because of physical injuries.”

Tim Ford said his brother didn’t take the news well that his sports career was over. “He took it real hard for a while, but then he came down and lived with me for a while in Monterey, Calif., where I was stationed with the military.”

In Monterey, Dale Ford got a job as an agent with New York Life Insurance, but after a year and a half he decided he didn’t like that work and wanted to move back to the Pacific Northwest.

Romance with WSU roots

Pamela Spoo first laid eyes on the handsome, 6-foot-5 athlete as he played baseball on Bailey Field within sight of her Streit-Perham dorm room window on the WSU campus.

Her girlfriend, dating another baseball player, helped with introductions at a party for players, Spoo recalled, and the relationship flourished. The couple married Feb. 19, 1969, in a wedding attended by 700 at Sand Point Community Church in Seattle.

Two years later, Dale and Pamela Ford and Tim and Gail Ford jointly bought a summer home on Whidbey Island, just south of Mukilteo. The beauty of Puget Sound was the backdrop for good times. The two couples would relax, fish and golf.

“Those were some of our good times together,’’ Tim Ford reflected.

During that time, Dale Ford worked as an independent real estate broker, eager to become wealthy, buying and selling commercial properties in the Seattle area, his brother said.

Then on Jan. 1, 1977, Ford received word that his close friend and college buddy, major league relief pitcher Danny Frisella, had been killed in a dune buggy accident near Phoenix.

“That news hit Dale real hard,’’ Tim Ford recalled. “If Dale had two real close friends, I think it would have been Danny and John Olerud.”

Dr. John “Ole” Olerud, Ford’s college-era friend, roommate and WSU baseball team captain, went on to play pro ball in California with “The Whale.” Olerud became a physician, faculty member at the University of Washington Dermatology Center and father of the famous first baseman, John G. Olerud.

“We were great friends and did things together,” Olerud said, recalling that while attending medical school in Seattle he played squash with Ford. Later, Ford helped Olerud coach his son’s basketball team in Bellevue.

During John Olerud Jr.’s great baseball career at WSU and later with the Toronto Blue Jays, “I kept thinking Dale would come walking out of the stands somewhere, someday, but that never happened,” Ole Olerud said.

The Seattle physician said he, too, frequently wonders what happened to the man who once was one of his closest friends. “I’ve even wondered if he ran afoul of some Mafia guys and ended up with one of those cement overcoats,” Olerud said.

In 1980, Dale and Pamela Ford had their first daughter, Danielle. Two years later, their second daughter, Samantha, was born.

“On the face of it, from what we saw, Dale was a doting father,” Tim Ford said.

But by 1987 the marriage was in trouble and the couple briefly separated. “I initiated the separation in hopes that things would repair themselves, but that didn’t happen,” Spoo said.

“Dale had trouble establishing himself outside of athletics,” she said. “He wasn’t able to hold onto any job very long and create success for himself and his family.

“We separated for a year or two, but he was not able to care for his children and financially support them, so, eventually, it was very difficult to see him, and I filed for divorce.”

Ford’s daughters, then 7 and 4 years old, would be raised by their mother and never see their father again.

“To the best of my knowledge, not one person I know has had any contact with Dale for about the last 25 years,” Spoo said.

“The last I heard, it was back in about 1988, was that he’d taken a job in California. It seemed to be a fresh start for him. He was enthusiastic about it. He called to talk to the girls one time, and then we didn’t hear from him again.”

“I know nothing about his life, literally, after that last phone call,” Spoo said. “So you can see my life with Dale was over a long time ago,” she said.

Tim Ford said since the divorce, his brother has had no contact with his daughters. “They’re both beautiful, well-adjusted young women, and that’s a credit to Pam.”

The girls’ mother has been “extremely good” about keeping their aunts, uncles and grandmother involved in their lives, he said. “We took them camping for years when they were kids and we still maintain that contact. Just last week, I was with them.”

One of Dale Ford’s daughters is a school teacher and the other is an interior designer. In exchange for agreeing to talk about his brother, Tim Ford insisted that neither of his nieces nor his elderly mother be contacted.

“We’ve done our best over the years to shield them from any problems, and we will continue down that road,” Tim Ford said. “As they get older, if they want to pursue it, that’s their option.”

The last time he recalled seeing his brother was in December 1987 at a memorial service in Olympia for their sister’s 17-year-old son, killed in a winter car accident near Leavenworth, Wash. “We’ve all talked about it, and that’s the last date any of us can remember seeing Dale.”

“No, I don’t think that death sent him over the edge,’’ Tim Ford said of his brother. “I think Dale had already gone over the edge. His whole life was starting to crumble around him. From this point on, I get real evasive, but I will say his professional life and his personal life had gone to hell, and Dale was not Dale.

“None of us ever believed alcohol or drugs were any part of it, and beyond that I don’t wish to comment,” Tim Ford said. He knows his brother was wrapped up in lawsuits related to business activities.

“I know of no criminal activity, but let’s say he lost his moral and ethical compass along the way, in my opinion, and he wasn’t taught that by our mom and dad,” Tim Ford said.

Choked up as he continued with the story, Tim Ford explained he and other family members “couldn’t reach out to him because we didn’t know where in the hell he was. He divorced himself from all his friends and, at that point, he divorced himself from (his) family as well. I guess that would be the right way to say that.”

“I went to a certain point and then I asked myself, ‘Do we really want him found?’ ” Tim Ford said. “I have since asked Pam that question and I have asked my sister that question. I will not ask that question of my mom.”

A friend with a baton

In 2007, six years after retiring as an enforcement officer and field supervisor with the Washington game department, Tim Ford decided to conduct his own search for his missing brother. It went nowhere, though, with only hints that Dale Ford might be living in California, perhaps occasionally working as a telemarketer.

In a new search for Ford begun last summer and commissioned by Cougfan.com, a sports enthusiast website, the missing person file from the Seattle Police Department that Tim Ford had not seen eventually pointed to his brother’s whereabouts.

The Santa Barbara police citation now included in that Seattle police file listed an office address in Santa Barbara. A search showed that office was leased by the Cielo Foundation for the Performing Arts, founded 46 years ago by insurance executive-turned-conductor Christopher Story. He didn’t return voice messages left at two telephone numbers.

But the nonprofit group’s annual 990 tax form provided the name of its accountant, Gary Gray, who recognized Dale Ford’s jail booking photo.

“Oh, he’s around the office all the time, very reclusive,” Gray said of Ford. “He has been working for Chris, kind of a dialing-for-dollars fundraiser guy for the foundation for years. I sort of have the sense he sleeps in the office.”

Others who recognized Dale Ford’s jail booking photo confirmed he’s an occasional visitor at Casa Esperanza – one of Santa Barbara’s largest homeless shelters. At the so-called “House of Hope,” homeless people with a thousand stories to tell can take a shower and get a warm meal, no questions asked.

When a third number was obtained for 86-year-old Christopher Story, he confirmed last week in a phone interview that Dale Ford has worked for the Cielo Foundation in Santa Barbara for at least a decade. Ford sells ads and raises money for the performing arts group that sponsors West Coast Symphony and Chamber Orchestra concerts in Santa Barbara, Story said.

Story said he had no clue about Ford’s illustrious sports background or personal history. “I didn’t hire him because of his athletic abilities. All I know about him is he likes to play the ponies and is a (horse racing) handicapper. He goes down to Ventura to play the horses.”

Story then provided his foundation’s office phone, answered May 15 by a man who confirmed he was, indeed, Dale Ford.

“How did you find me?” Ford said repeatedly, sounding stunned, flabbergasted. When told it was public records that ultimately led to his doorstep, Ford said, “Oh, no, I’m not in any public records.”

It was explained to Ford that, while he certainly was under no obligation to answer questions about his mysterious life, a lot of people remember his tremendous legacy at WSU and wonder what became of him.

“I choose not to talk to you,’’ Ford said in a calm voice, before saying goodbye.

The word of Dale Ford’s confirmed whereabouts came as a shock to Tim Ford, leaving him with raw emotions, uncertain what to do now, if anything.

He previously had “toyed with the idea” of traveling to California to search for his brother, but dismissed that idea and didn’t tell his mother, who lives near Olympia.

“She went through all this crap, and then lost a son, in essence,” he said. “I will not put her through that again. Now, if he walks back into her life, then I guess that’s his decision and that’s her choice.”

Tim Ford said his 90-year-old mother is still very active and doesn’t frequently ask about her missing son. “I don’t talk to her unless she brings it up. It does come up but we don’t dwell on it.

“Let’s just say she’s heartbroken. Wouldn’t you be?”

Tim Ford said he isn’t sure what his reaction would be if his long-lost brother showed up tomorrow, but he doesn’t think there’s a likelihood of that happening.

“I guess how I look at it is, before I die, I don’t want any answers from him, because he probably couldn’t give me any answers. And, he may very well no longer consider us his family.”

“I’m not going to sit down and dwell on the past. I guess I’d be more interested to know if Dale has gotten on with his life and is happy. If he is and he’s happy without us, then let’s leave it that way. We had good times and we’ll just kick the bad times out the door and not dwell on them.”