Family believes Iraq fires caused soldier’s death

Danielle Nienajadlo’s mother, Lindsay Weidman, left, and sister Michelle Scheibner hold the folded flag given to them upon Nienajadlo’s death in 2009. Nienajadlo died from leukemia, which her family believes resulted from exposure to one of the massive “burn pits” in Iraq. (Tyler Tjomsland)Buy a print of this photo

Lindsay Weidman clutches a picture of her daughter tight to her chest. She’ll carry it during Saturday’s Armed Forces Torchlight Parade in

downtown Spokane.

Her little Danielle, who grew from sweet girl into toughened soldier and then caring mother of three boys, died three years ago.

“It’s hard to accept that she is gone,” Weidman said. “She shouldn’t be.”

Danielle Nienajadlo joined the Army after graduating from Lewis and Clark High School in 1995 with the last name of Scheibner. She loved the military, was strong and fit, and spent 13 years as a soldier serving around the world, including in Iraq.

Then her life fell apart. Duty killed Nienajadlo in 2009, said Weidman, but it wasn’t battle wounds or an accident. It was an aggressive form of leukemia.

She became ill after months of living and working near one of the notorious “burn pits” in Iraq.

They were the bonfires of war waste – a toxic mess of clothes, fuel, garbage, supplies and anything else the military and its contractors deemed unworthy for shipping back to the United States.

The stench and smoke invaded Danielle. She coughed up mixtures of blood and black phlegm while stationed at Joint Base Balad.

She would call her mom and complain of sores and bruises across her body. She told her sister that she had splitting headaches and that she was losing weight.

She sent alarming photos home and her family pleaded with her to cut through the red tape and get medical attention.

Her reports to superiors were met with accusations of laziness.

“Unbelievable,” said her younger sister, Michelle Scheibner.

Danielle was finally sent to Walter Reed Army Medical Center and diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukemia.

She became one among hundreds of soldiers brought home from the war to battle cancers and other diseases. Many – though not all – blame the burn pits for their illnesses, and class-action litigation is pending in federal court.

A study published late last year by the National Academy of Sciences determined it was too early to tell if the fires posed health risks to troops. The military has not stated that the smoke and fumes from the approximately 80 burn pits may be linked to the sickness and death of its soldiers.

But samples taken in 2007 and 2009 from the Balad base determined some pollutant levels were higher than in the world’s dirtiest cities, including Beijing. The Balad pit was extinguished in 2009.

The open fires reportedly were receptacles for medical wastes, tires, Styrofoam, batteries, plastics such as water bottles, coated metals, electronic components and in some cases even entire vehicles.

Both private and military researchers and medical officials worry that the burn pits exposed troops to toxins, potentially resulting in higher rates of various illnesses.

Michelle Scheibner said the military did a poor job of helping families get answers.

“Once the funeral is over, that’s it. Period,” she said. “We have questions. Something happened to my sister in Iraq and nobody seems to care.”

The military is quick to laud the lives of those who die in battle or tragedy. It isn’t so good at celebrating the contributions of those who died in support roles.

Danielle was a light wheel mechanic – a Bravo 63 in Army slang. She helped keep the engines of war in tip-top shape. It was proud work for a woman who had every intention of serving her 20 years in the Army and then some. It would be a résumé item that would have one day impressed an employer and most likely her three sons – Isaiah, Ian and Titan – all of whom were younger than 10 when she died March 20, 2009.

Weidman remains in mourning. She was with her daughter when she died.

Danielle had been transferred to the University of Washington Medical Center for a bone marrow transplant. But her immune system, compromised from the chemotherapy, couldn’t fight off infection and she died of sepsis.

“I watched as her spirit rose,” said Weidman. “I am keeping her memory alive.”

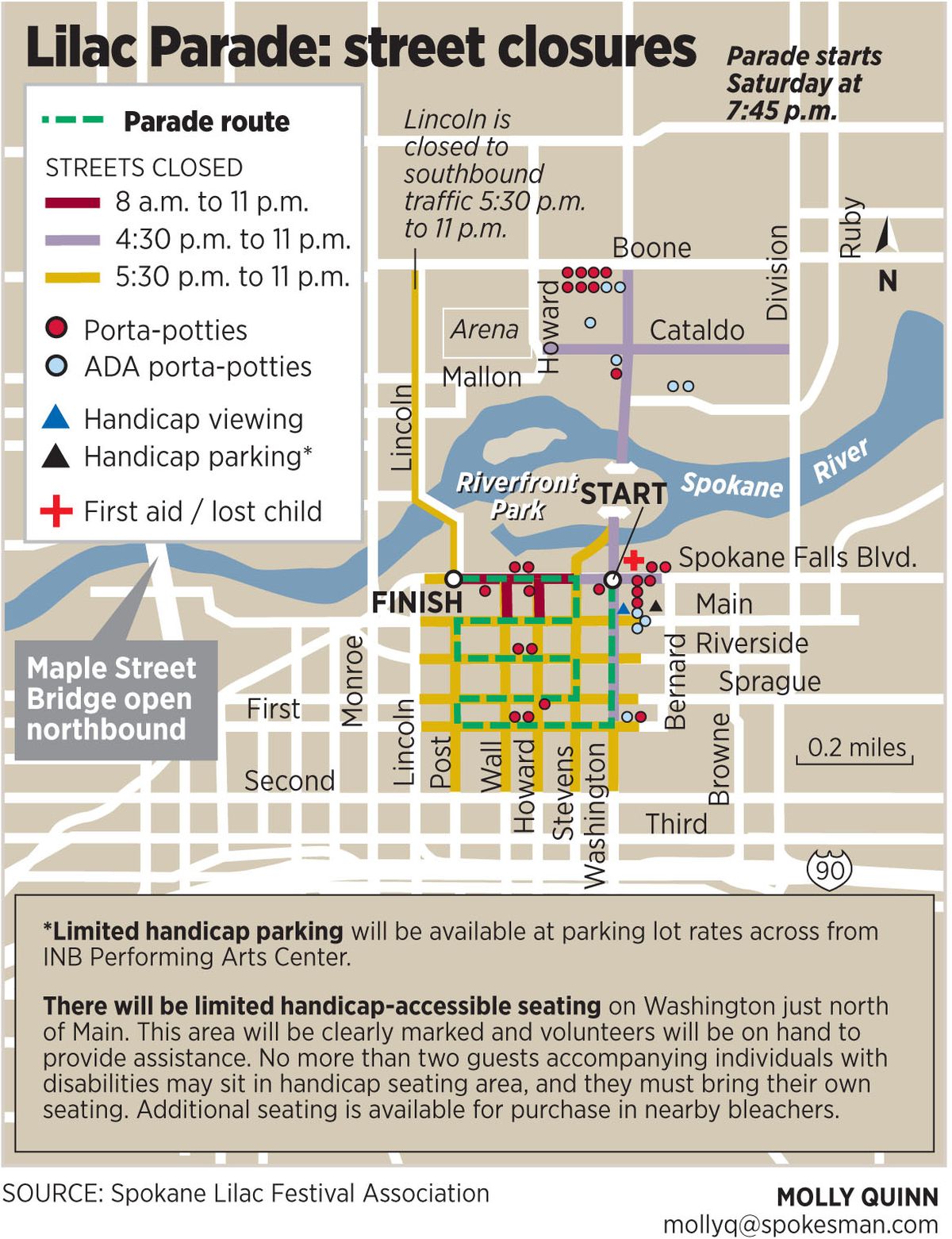

On Saturday she will share her daughter with the Spokane community as a Gold Star Mother, walking in the Lilac Parade with other mothers who lost children to military service.

“Danielle would want answers,” said Michelle Scheibner. “Her family deserves to know.”