Tribe puts Lake Roosevelt walleye on table - for dinner, debate

The Spokane Tribe’s fish program manager couldn’t avoid the subject last week, not even at a Natural Resources Career Day presentation on Thursday.

Brian Crossley had not been able to say much about the tribe’s proposed walleye management plan since it leaked to the public a week earlier, causing a firestorm among walleye fishermen. But school seemed like a good place to start the dialogue.

“I used the analogy of having one cow on a 10-acre pasture,” he said, noting the cow would get big and fat, tempting the owner to think it would be better to put 10 cows on the pasture.

“But instead of 10 fat cows you’d end up with skinny cows,” he said, noting the students had no trouble understanding the concept of carrying capacity.

That’s the problem with walleyes at Lake Roosevelt, he said: “It’s a food pyramid thing. The prey base always has to be higher density than the predator base. Right now, the pyramid is upside down.”

On that point, almost everyone involved with Lake Roosevelt fisheries agrees. Biologists for the Spokane and Colville tribes, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Eastern Washington University and even many – not all – anglers say there’s an overabundance of small, underweight non-native walleye and a dearth of forage fish in the reservoir.

Still, walleye anglers lit up Internet blogs and chat rooms last week.

George Allen, president of the Spokane Walleye Club and Lake Roosevelt walleye fisherman for 30 years, said he is angered by the tribe’s bounty plan. Some anglers were threatening to boycott tribal businesses, he said.

“They want to go in where the season is closed to the public and pay people to catch a legal game fish,” he said. “It’s not going to work, for one thing. It’s the principal more than anything else that gripes us.

“It’s just another plan to blame the walleye for every problem in the lake.”

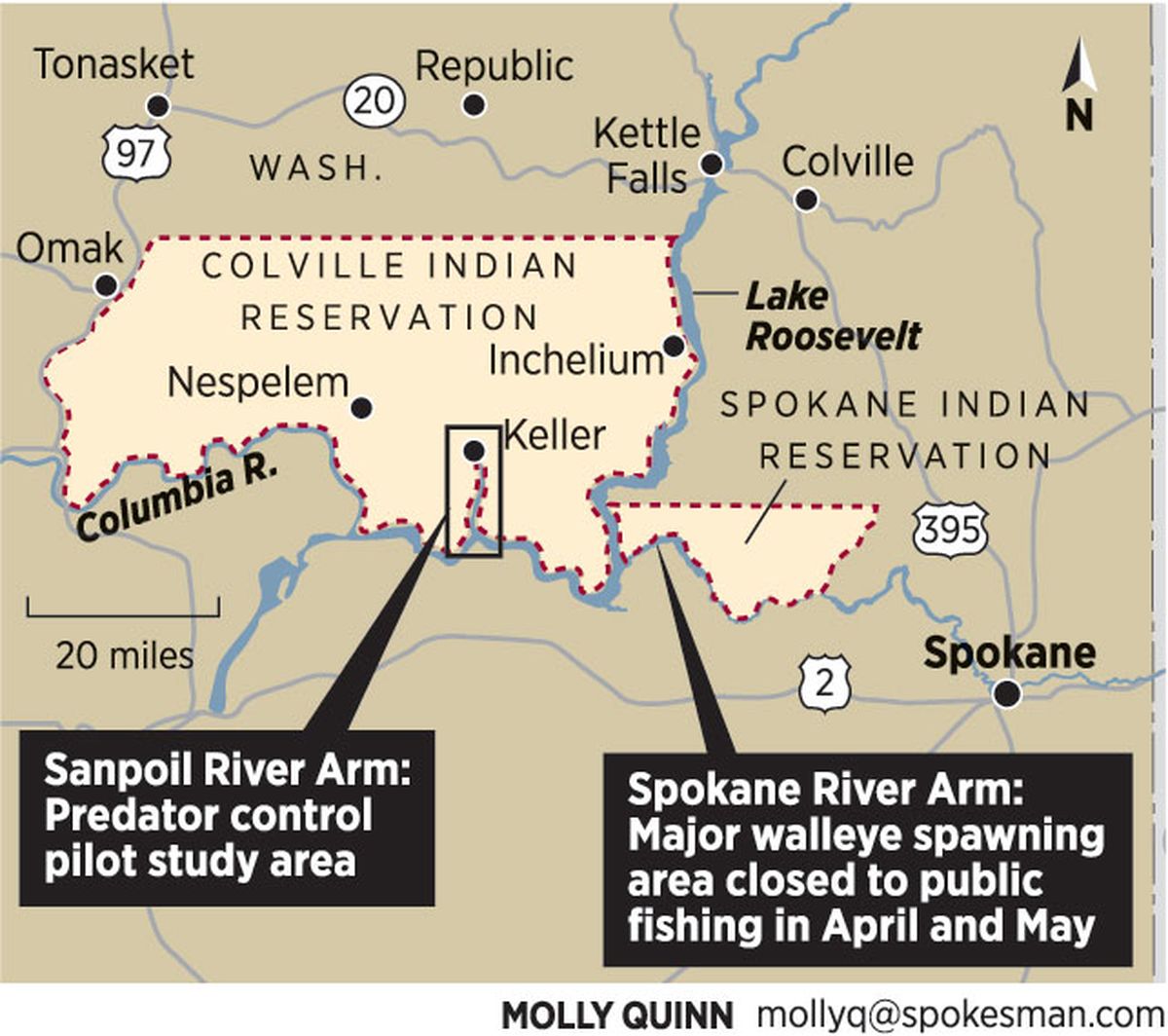

Although they could still change their minds, tribal officials said Thursday they plan to pay tribal members $2-$4 from tribe funds for each walleye they remove with hook and line. The bounty period is April-May. Fish must be caught in Lake Roosevelt’s Spokane River Arm, which borders the Spokane Indian Reservation.

While Lake Roosevelt backs up 150 miles behind Grand Coulee Dam, the Spokane Arm is considered the most productive spawning area for the reservoir’s walleye.

In 1985, the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission enacted an April 1-May 30 spawning season closure on walleye in the Spokane Arm upstream from the Highway 25 bridge. Tribal members have treaty rights to fish for walleyes there with no season or limits, although they have taken a very small percentage of the fish, surveys show.

Even a cash incentive isn’t likely to encourage tribal members to take a significant number of the walleye population, Crossley said.

The spring closure for non-tribal anglers was backed by walleye fishermen who wanted to assure that Roosevelt’s major walleye spawning area would be a sanctuary for their favorite fish to reproduce.

Walleye anglers also supported a slot limit that allows anglers to keep only walleye larger than 16 inches and no more than one a day longer than 22 inches.

“We want to protect our big fish,” Allen said, noting that walleye anglers prize trophy fish to catch-and-release so they can spawn and perpetuate the fishery.

But Crossley said research had already indicated the spawning closure and slot limit would be counterproductive.

“In the early 1970s, the average length of Roosevelt walleye was 18.5 inches,” he said, citing state-managed fish surveys. “By the mid-’80s, the average length had dropped to 14 inches.

“You scratch your head: why did they start protecting walleye spawners when they could see the average size was going down and the prey base was going down, including native minnows and suckers?”

“The rules are politically motivated,” said Chris Donley, WDFW fisheries biologist. “We tried to keep everyone happy. The problem is that walleye anglers don’t catch and keep enough walleyes or bass under this system.”

Although he’d like to see a smoother public outreach and education effort, Donley agreed the Spokane Tribe’s plan to harvest more fish in the Spokane Arm is a step in the right direction.

Last year, Donley formally proposed dropping the Spokane Arm spring fishing closure and the slot limit on walleyes. WDFW did not advance that proposal, but John Whalen, the agency’s regional fisheries manager, said the proposals likely will be presented for public comment later this year.

Walleye fishermen are talking it over.

“Attitudes have changed a lot since the state put the spawning closure on the Spokane Arm,” Allen said. “I know lifting it is likely to be a proposal for next year.”

Ironically, while the Spokane Tribe stirred the pot by proposing a bounty on Spokane Arm walleyes, the Colville Tribe is meeting less resistance to a pilot project experimenting with gillnets to reduce walleye numbers in the Sanpoil Arm, which extends into their reservation.

Bret Nine, the Colville’s fish program manager, said the Sanpoil Arm is not a major walleye spawning area. But research has documented walleyes and smallmouth bass moving by the thousands into the Sanpoil each spring. At the constriction in the Sanpoil Arm near Keller Campground, the predators ambush and feast on young outmigrating kokanee and wild redband trout, he said.

Holly McLellan, a former EWU research biologist who works for the Colvilles, said research in 2009-2010 found walleye, primarily, and smallmouth bass, to a lesser extent, were consuming:

• 95 percent of the kokanee fry being released in the Sanpoil,

• 40 percent of kokanee yearlings,

• 24 percent of redband trout yearlings,

• 27 percent of 2-3-year-old redbands.

While researchers are trying other methods of releasing hatchery kokanee, they need to thin out that gantlet of voracious walleyes to get more survival. Researchers found as many as 70 kokanee in one walleye stomach.

Last year, the Colville Tribe dropped the Sanpoil Arm spring closure and encouraged anglers to target walleye where they concentrate above the campground.

Allen said the biggest impact on trout and kokanee numbers are reservoir drawdowns and hydropower operations that flush fish over Grand Coulee Dam and out of Lake Roosevelt.

Tribal researchers agree that big water years, such as last year, have major impacts on the fish.

“But the problems with entrainment make it even more important to reduce the walleyes and get the fisheries throughout the system in better balance,” Crossley said.

Everything’s out of whack, he said, including the regulations.

“We’re protecting non-native walleye spawners that will produce up to 400,000 eggs and we have no spawning protections for native redband trout that will produce only 3,000 eggs,” he said.

Meanwhile, the tribes have been pumping federal money into hatchery and native species protection programs only to see high percentage of the effort going down the gullets of walleyes.

Even efforts to bring back sturgeon are being impacted by walleyes, although proof is hard to find. Without a boney structure, young sturgeon larvae decompose so quickly in a fish’s stomach it’s difficult to find the evidence they’ve been eaten.

Much of the money for kokanee and trout recovery, research and hatchery production comes from the Bonneville Power Administration to mitigate the damage Columbia River dams inflicted on native fisheries, especially salmon.

Kokanee – remnants of pre-dams sockeye runs – are native fish and the only salmon remaining in Spokane Tribe waters to feed members – and wildlife such as eagles, Crossley said.

But the scientists who work for BPA to review the research the tribes are doing on Lake Roosevelt have been criticizing trout and kokanee restoration efforts because of their lack of attention to predators.

Program funding could be reduced if predation isn’t addressed.

“There aren’t any trout clubs on the lake, but there are a lot of trout and kokanee fishermen,” Nine said. “You have to consider that angle, too.”

“I think what we’re all striving for is a balanced ecosystem approach,” said Tim Peone, manager of the Spokane Tribal Hatchery that raises many of the kokanee stocked in the lake. “It’s not a matter of getting rid of everything but the native fish. That can’t be done. But we could manage for a better balance.”