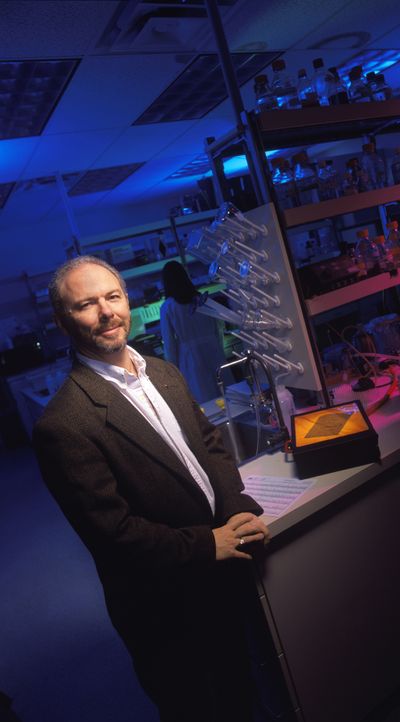

Researcher: Exposure to toxins can alter DNA

WSU epigenetics expert finds evidence changes affect future generations

PULLMAN – Women with ovarian disease may have inherited it from great grandmothers who were exposed to toxic chemicals decades ago, according to a study by Washington State University researchers.

A series of papers being rolled out this year by WSU’s Michael Skinner and researchers from other universities is strengthening findings that toxic exposures and other events have the ability to alter the genes of future generations.

And it’s this transgenerational effect that may help research scientists, drug companies and regulators better understand the pathways of disease – a mystery that continues to vex even the brightest minds in medicine.

Skinner is a biological sciences professor and his work at Skinner Laboratory centers on epigenetics – how outside influences can alter the DNA sequence.

Epigenetics is an emerging field of research that challenges today’s scientific paradigm – what Skinner calls “genetic determinism” – that holds that our DNA sequence is locked in a kind of black box and thus genes cannot be altered by an outside influence.

The controversy has made Skinner’s work both notable and more difficult.

His belief and work that a person’s genes may be shaped by an ancestor’s life experiences is widely published and was even part of a BBC documentary, “The Ghost in Your Genes.”

But epigenetics has not supplanted determinism, and thus research dollars are more difficult to secure from organizations such as the National Institutes of Health.

“If you’re not doing something controversial,” he said, “you’re not doing something important.”

Skinner’s lab did receive a $1.7 million grant from the U.S. Department of Defense to look into what genetic harm may be done by chemical exposure during military conflicts such as the Iraq War.

The research exposed rats, not humans. Previous research into wartime chemical exposure focused on the harm done to troops, such as poisoning from Agent Orange, the chemical used to defoliate the jungles of Vietnam.

Skinner’s work now looks into whether such exposures may alter a person’s genetics and make subsequent generations, for example, more susceptible to diseases.

Japanese researchers are using the work to look into whether the descendents of atomic bomb survivors may be more susceptible to cancer and other diseases because of epigenetic changes inherited from their ancestors.

In the research of epigenetics and ovarian disease published in journal PLoS One, researchers exposed gestating rats to environmental toxins during a specific time in the pregnancy. The exposure affected the molecular factors surrounding the DNA, in effect determining which genes in the DNA are switched on or off in the developing baby rat. Skinner said that genetic sequence was then passed along to future generations of rats, in this case a change that caused a genetic link to ovarian disease.

“Our research suggests, then, that if a person’s great grandmother were exposed to an environmental toxin during a specific time during her pregnancy, the developing fetus … would have a different gene sequence and that gets passed along even though the person was never exposed directly to the toxin,” he said.

In another peer-review study published last month by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Skinner and researcher David Crews, a professor of psychology and zoology at the University of Texas, exposed gestating rats to vinclozolin, a commonly used fungicide used on vegetables and fruits.

Their study showed that the descendents of the exposed rats were more obese, anxious and less sociable than the descendents of rats that were not exposed.

The research has made Skinner a public speaker and epigenetics spokesman. He presented his findings recently to a meeting of the Spokane chapter of the Autism Society of Washington.

While he couldn’t offer explanations for the disease that research now estimates affects one in 88 children, Skinner presented possible scenarios about the rising prevalence of the disease following a century of rapid industrialization.

“What he tells us is that perhaps something from our past is having an effect today,” said Kristy Wessels, state president of ASW.

From his lab in the Biological Sciences Building at WSU Skinner smoothly discusses the history of epigenetics to dampen its rebel reputation and to explain how it simply offers other possibilities as scientists continue to ponder the complexities of genetics a decade after the human genome was first unraveled.

C.H. Waddington came up with the term epigenetics in 1942 – more than a decade before James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA in 1953 that revolutionized physiology and earned the duo a Nobel Prize.

Their work swamped Waddington’s concept of epigenetics as a way to explain how genes may be influenced by surroundings, said Skinner, who keeps a bobblehead of Watson in his office.

Rather than give rise to helplessness about a person’s fate being tied to something their great grandmother may have been exposed to, Skinner said understanding the role of epigenetics may help researchers find remedies.

“I would always argue that knowing is better than not,” he said.