Education investment: College students face tough choices

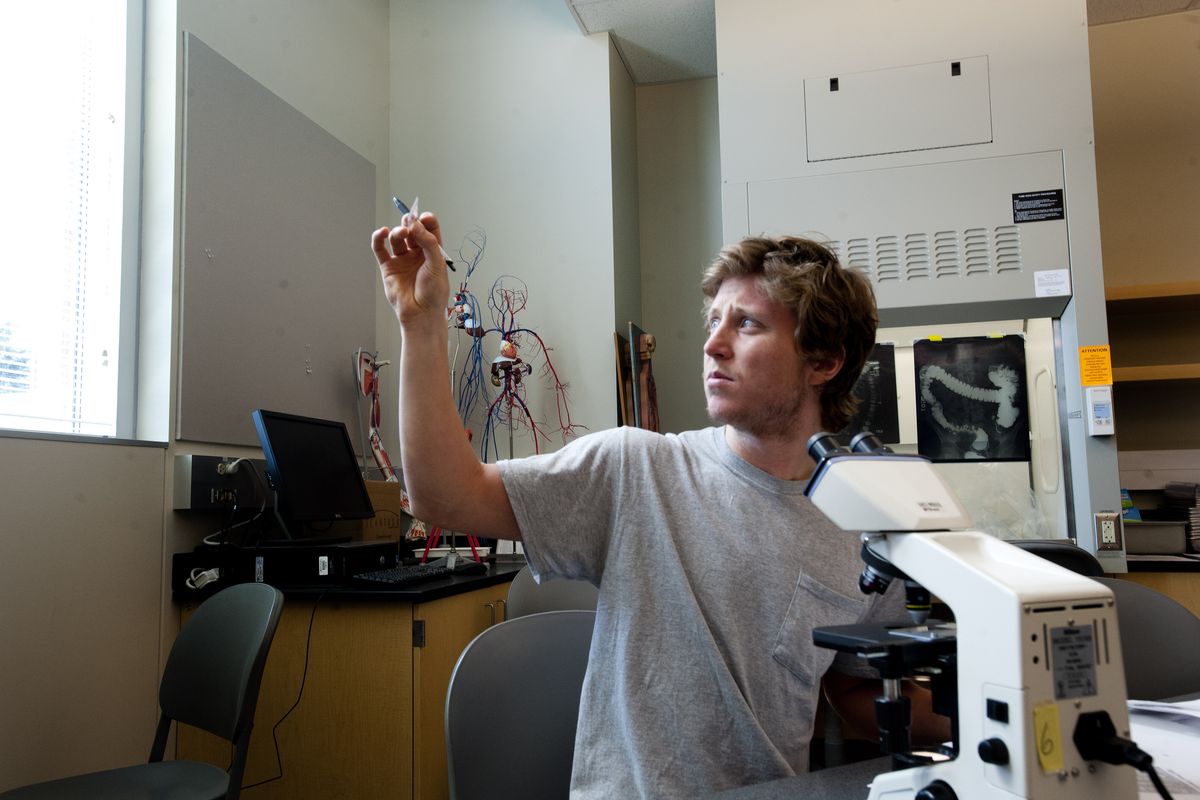

C.J. Barschig, 26, peers through a microscope at human stomach and intestine linings July 5 during an Anatomy and Physiology 240 class taught by Gary Blevins at Spokane Falls Community College. The class is a basic requirement for health-related professions. (Tyler Tjomsland)Buy a print of this photo

Until about 2007, deciding on a college degree typically involved choosing an area of interest or aptitude, then staying in college long enough to graduate.

But with the cost of a college education skyrocketing and the economy still struggling, the question of choosing a marketable major becomes much more urgent.

In the Inland Northwest, the degree most frequently conferred by area colleges and universities is business, according to a recent analysis by The Spokesman-Review. Social science degrees rank second, followed by health-related degrees, liberal arts and engineering. The analysis looked at both bachelors and associates degrees awarded by Washington State University, Gonzaga University, Whitworth University, Eastern Washington University, University of Idaho, North Idaho College, Spokane Falls Community College and Spokane Community College.

While that list roughly matches national figures, it doesn’t square with the expectation among workforce experts that the skills most in demand in coming years will be in science, technology, engineering and math disciplines, or STEM.

There are multiple reasons for that disconnect, but a lack of solid information on how a particular degree correlates with a specific job and salary is one that’s receiving new attention. Such information hasn’t been readily available to students.

A bill introduced by Sen. Ron Wyden, an Oregon Democrat, called the “Student Right to Know Before You Go” act, has been proposed to help students make such informed choices.

“There was a time when going to college was a cost. The loans were fairly manageable,” said Tom Towslee, Wyden’s Oregon spokesman. “Now it’s an investment, and you need to know the return you are going to get on the investment. What kinds of jobs are going to be out there?”

Figuring out ‘payoff’ is difficult

Tuition has risen more than 20 percent on average nationally and as much as 70 percent in Washington during the past five years, data shows. To pay those rapidly rising costs, students are taking on subsidized and private debt.

College graduates owe a collective $1 trillion, which surpasses credit card and car loan debts.

Unlike other major life investments, such as buying a house or a car, it can be difficult for a college student to figure out the return on their investment.

“The reality is you can find out more about a used car than you can a college education,” Towslee said.

America’s college system, for the most part, is not structured so a degree is tied to a specific job, but rather a cluster of job prospects.

Figuring out the relative “payoff” of a particular degree is difficult, said Mark Schneider, vice president of American Institutes for Research – a nonprofit, nonpartisan behavioral and social science research organization founded in 1946.

“That piece of information is missing, and we are only beginning to crack this code; an objective value that says my degree from this university will earn me this much money,” Schneider said.

His research is aimed at “merging the school-level data with the profession, and that’s the Holy Grail,” he said. “Not just a certain degree, but a certain degree from a certain school. That’s the level of data we need.”

Data on Virginia colleges and universities will be released first, and five other states will follow: Nevada, Colorado, Texas, Tennessee and Arkansas.

“We have a fundamental data problem in trying to figure out what degrees lead to what occupations,” Schneider said. “My work is merging the school level data with the profession. Researchers can’t really track what a person is using in positions, colleges need to do that.”

The six states were picked because they volunteered for the study; Virginia now has legislation to make available how much graduates from the state’s colleges and universities are earning in a job.

That information was made available by merging two data systems that already existed, Schneider explained. The public institutions report student records or transcript information, and unemployment insurance records reveal whether a person is employed and their annual salary.

“Most states have these data systems, and just now they are making that information available,” Schneider said.

Wyden’s proposed legislation would offer similar information, and then some. The act would also include institutions nationwide.

According to the act, students would be able to find out how long it should take to complete a degree, the success of other people in completing the degree program and how long it takes; rates of remedial enrollment, credit accumulation and graduation; average cost of the degree before and after financial aid, and average debt accumulated; and how employable the graduate will be when they are done and their average annual salary.

Federal officials have already taken one step to help make sure students aren’t wasting time and money. A regulation enacted on July 1 revokes federal grants and loans to for-profit schools and vocational certificate programs at community colleges that fail to enable a student to find a job with a sufficient income to pay back their loans.

Does this cost-benefit view of higher education mean the liberal arts degree is doomed?

No, although even in 2004, the American Council on Education noted in a report that market forces posed a challenge to the Jeffersonian ideal of higher education: “At its extreme, competition can overtake more traditional academic values such as unfettered inquiry, access and choice for a diverse student population, and critical social commentary.”

Schneider has a slightly different take: “If you are majoring in some esoteric, liberal arts area, more power to you,” he said. “The nation needs people like this. But you have to do it because you love it. It’s like taking a vow of poverty.”

He continued, “But if you look at the bachelor’s degree in business or marketing, or accounting, there are big payoffs in those. If you look at degrees in engineering or particular types of engineering, there’s a big payoff.”

Patricia Killen, Gonzaga University academic vice president, said the elements of a liberal arts education still have a place.

“When the economy gets shaky, students tend to be oriented toward majors they tend to think will be tied to jobs,” she said. “But it’s not clear that is the best long-term investment.”

She added, “One national study of undergraduate business education done by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching urges business programs to peel back business requirements and add more liberal arts requirements … to think more critically, to bring multiple perspectives to the job and see the whole picture.”

Another study suggests “for people to be effective in jobs in the long haul, they need the kinds of skills and perspectives that a classic liberal arts degree provides.”

And Gonzaga University, for one, remains committed to “a classical liberal arts and sciences core curriculum because we are still convinced that kind of educational experience is vital to cultivating the imagination, the character, the habits and skills of mind that are needed to succeed and contribute to society.”

More need to graduate, with the right degrees

Workforce demands are changing as America crawls out of a recession, baby boomers retire and there are advances in science and technology.

By 2018, America will need 22 million new college degrees, “but will fall short of that number by at least 3 million post-secondary degrees, associates or better,” according to a study from the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

Part of the problem is that not enough students graduate from college despite enrollment spikes.

In 2011, the graduation rate for bachelor’s degrees nationally was 56 percent; so only slightly more than half of the students who started college full time in 2006 earned a degree. That figure was only 20.4 percent for associate’s degrees or two-year programs, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. The increasing cost of college means more students drop out due to an inability to pay, researchers say. In addition, more students are showing up at colleges woefully unprepared for the more rigorous level of academics.

But another major issue is that students get to college and become disheartened by the job outlook for their desired field of study and, unable or unwilling to transfer to a more marketable major, drop out.

There is wide agreement on what degrees will yield good jobs.

According to National Association of College and Employers, graduates most likely to receive a job offer are those earning degrees in accounting, engineering, computer science, economics and business administration.

However, only three of those degrees are among the top 10 most commonly earned associate’s and bachelor’s degrees regionally and nationwide.

According to the Georgetown University study, there will be eight million jobs in the STEM fields by 2018. But data reveal a small minority of students graduating with degrees in those areas.

In the Inland Northwest, the top four growth industries are health care, manufacturing, finance and insurance, and most of the growth in the final category is among health insurers, said Doug Tweedy, the state’s labor economist for the Spokane area. “Those (jobs) match up well with (degrees in) business, the health professions programs, engineering and engineering technologies,” he said.

Anthony Carnevale, director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, said, “In the top 10 degrees, health care is dependable. That sector of the economy is going to increase.”

He added, “Anything in STEM is a pretty good bet, and then business, not as sure of a bet, but it’s a good bet. Teaching is a pretty good bet, but not in the immediate term.”

Carnevale said that because of the aging baby boomer demographic, college students should be looking at areas where there’s an older workforce, such as education, as well as anything involving care for the elderly.

“Counseling and community services for the elderly people will increase in demand,” he said. As far as education, “the average age of the people in the occupation is relatively high, so we are going to get lots of retirements in the next 15 years.”

Schneider, of the American Institutes for Research, suggests that a more comprehensive approach is needed to the challenge of aligning the supply and demand of college graduates.

“If the next wave of jobs is expected to be in the STEM fields, no wonder there’s a big concern for where companies will have to look in order to find educated, qualified employees,” Schneider said. “A recent report talked about how thin the knowledge is in fourth, eighth and 12th grade students in science. So we are not doing a particularly good job with our feeder schools.”

He added, “If we believe we need more STEM students, we should be paying graduates in those areas more. We need to get the market signals straight. Why would I become a mathematician if I’m going to make $35,000 when I could be a business major and get paid $70,000?”