College’s rising cost steering students to private, smaller institutions

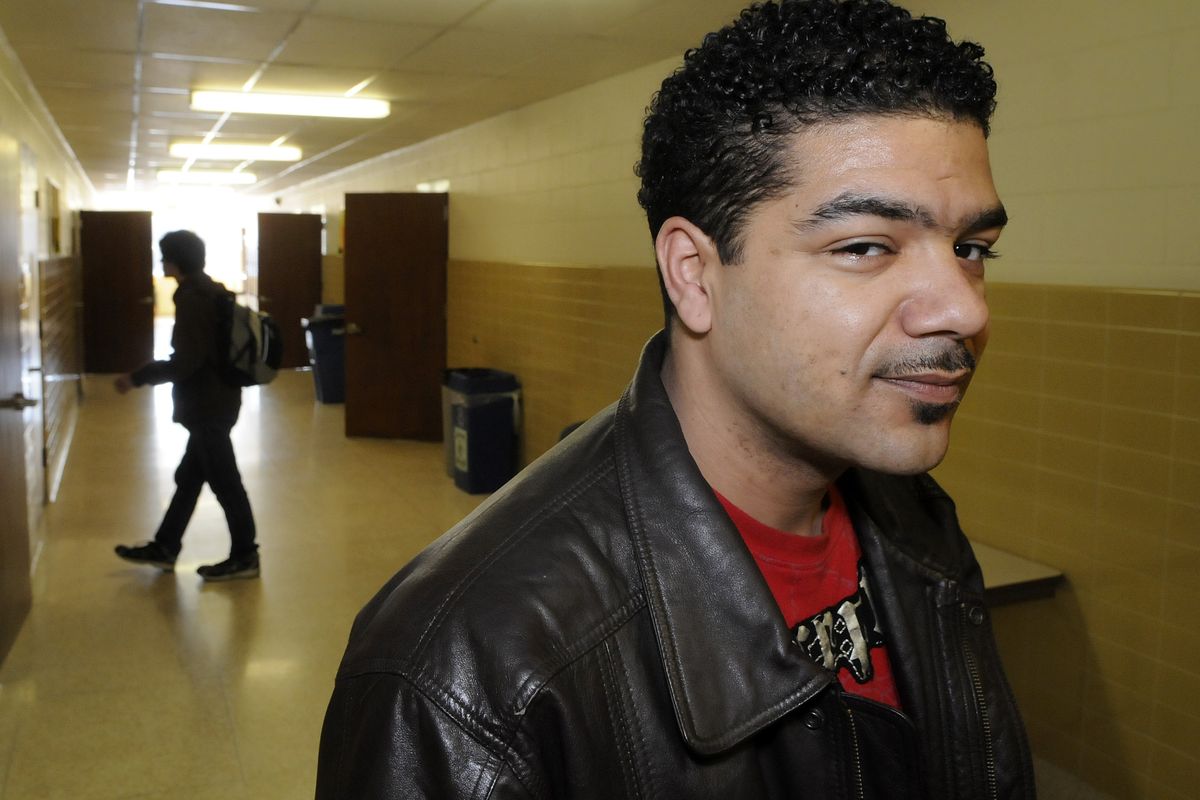

Demetrius Dennis shopped carefully to find the best college education for the lowest price.

“I reviewed the departments, programs offered and cost of tuition,” said Dennis, 34. “Financing contributed at least 75 percent of the deciding factor when I chose a transfer college.”

The Lakewood, Wash., resident had already saved about $20,000 on a bachelor’s degree in journalism by attending Pierce Community College before determining Eastern Washington University offered the best value to finish his studies.

EWU “provides the most reasonable tuition-to-education ratio available in the state,” Dennis said.

As postsecondary degrees become increasingly expensive, prospective college students are considering smaller state universities and community colleges as alternatives for higher education. They are also paying closer attention to private colleges, high school/college dual-enrollment programs and cheaper colleges in neighboring states.

Public universities in Washington and Idaho, like those in many other states, have hiked their tuition dramatically in the past five years, and another increase could be coming in the fall.

Since 2007-’08, Washington State University’s tuition has risen 57 percent. The University of Washington’s tuition has increased a whopping 66 percent in that time, and Eastern Washington University’s increase is nearly 50 percent.

Boosts at Idaho higher ed institutions have been less dramatic: Tuition at both North Idaho College and the University of Idaho has increased by about 30 percent.

In the 2010-’11 school year, an on-campus, first-time, Washington resident student attending EWU paid $18,841 for one year; at WSU it was $23,611.

Federal financial aid has not kept pace with those rising prices.

Among Pacific Northwest states, Idaho provided the least state and local financial aid to college students, according to a report released this month.

And Washington’s State Need Grant is spread thin because of record enrollment and poorer students.

As the cost of a college degree rises, so does employers’ demand for those degrees, according to a recent report by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. By 2018, at least 63 percent of all jobs nationally will require a postsecondary degree; the prediction for Washington is 67 percent and in Idaho 61 percent.

College affordability is one reason why the United States has slipped from No. 1 to No. 16 in college graduation rates in the world, according the U.S. Department of Education.

Costs shifted to students

Tuition increases and state cuts to higher education are directly correlated, college officials say.

A bill passed by Washington lawmakers last year allows colleges and universities to raise rates as they deem necessary during the next four years. For 2011-’12, the state’s two-year and four-year institutions implemented the highest yearly tuition increase yet – 20 percent at the University of Washington.

“My overall take is what we’ve done is basically cost-shift the money onto students and their families,” said state Sen. David Frockt, D-Seattle.

Tuition increases for 2012-’13 are again tied to Washington’s biennial budget; college officials are waiting to see what the Legislature does with the supplemental budget it’s working on now.

“My challenge is this is virtually a zero-sum game,” said Washington State University President Elson Floyd. “We can’t keep using tuition as a panacea to offset expenses. Our families can’t sustain it. No one can sustain a 16 percent increase year after year.”

He added, “We can cut people and work to be as efficient as possible, but you can only cut so much before you erode the quality of your product.”

One of Gov. Chris Gregoire’s proposed solutions to help with higher education funding is a half-cent sales tax increase, which would need approval of the Legislature as well as voters.

But that “is a risky proposition because first the Legislature has to endorse a budget without the tax. Then the tax proposal has to go on the ballot,” Floyd said. If that doesn’t pass, “we are up a creek.”

‘No one really wants to help you’

Sam Director, a freshman at Whitworth University, didn’t plan on going to a private university. But when he started shopping, the Oregon resident discovered it was cheaper.

“It was a process of elimination,” Director said. To go to an Oregon public university, comparable to one in Washington, would cost about the same as going to Whitworth.

Private colleges don’t rely on public funding and frequently have hefty endowments that help defray tuition costs and increase scholarship possibilities. And tuition increases among private universities have been less steep – around 20 percent at Whitworth and Gonzaga University over the past five years.

For his 3.8 GPA and 2,110 SAT score, Director received a $16,000 scholarship at Whitworth. The University of Oregon offered him only $2,000 for his academic achievements. Plus, Whitworth gave him scholarships for extracurricular activities, such as debate.

“For a middle-class white person, no one really wants to help you,” Director said. “The money was definitely a factor. I wouldn’t have gone to a private school if it was going to cost me more.”

With a dramatic increase in college enrollment nationally and statewide, there’s been a boost in high-need students, which has spread state grants thin.

More than 25,000 eligible students who applied for Washington’s State Need Grant in 2011 did not receive any money because of the burgeoning number of students from lower-income levels seeking that assistance. In 2007, fewer than 2,000 eligible students were denied a grant.

“Up until the recession, Washington had done a good job of filling students’ needs with the State Need Grant,” Frockt said. “I think the people who are really getting hit are the people in the middle.”

The federal Pell Grant, which is for the neediest students, has remained steady the past two years. The average award is $5,500 per year, said Rachelle Sharpe, director of student financial assistance for Washington’s Higher Education Coordinating Board. Most Pell Grant recipients have household income of $30,000 or less a year.

Student loan debt is taking up the slack in financial aid programs and state support.

The average college student graduates with $25,000 in student loan debt. A Washington report found a 20 percent jump in the student debt load in the last few years, which Frockt calls a “crisis.”

Partly in response to the changing environment for financing, Frockt is sponsoring a bill that would require colleges and universities to provide financial aid counseling to students who borrow money for their education.

Frockt’s plan would require institutions to talk to students about loan performance requirements and repayment rules and give them an overview of financial literacy, basic money management skills and advice from previous students who received financial aid.

Additionally, the bill would require colleges and universities to list careers and starting salaries graduates could expect, he said.

Frockt noted that the student loan debt problem may become even worse because Washington lawmakers are considering taking money away from the state work-study program, in which students earn money working in on-campus jobs.

“The state work-study program for kids who don’t qualify for the State Need Grant, that’s their financial aid,” Frockt said. “We are just cutting off access. It’s not a good situation.”

Running Start enrollment up sharply

While some high school students wait until they’re upperclassmen to think about college, others start considering their postsecondary options sooner.

Spokane resident Adriana Diaz took advantage of Running Start, a program in which Washington students can be dually enrolled in college and high school starting their junior year. The cost: books and about $150 in fees.

Diaz chose that option because “my college situation was altered drastically by the tuition hikes,” she said. “By enrolling in Running Start at EWU, I cut my total cost in half.”

Enrollment in the program has increased 16 percent statewide since 2006, according to state data. At Spokane Community College, Running Start enrollment jumped 20 percent during the same time period. Lora Culley, mother of four, knows the importance of a college degree for her children. But “I cringe every time they talk about tuition increases on the news,” she said. “I’m just wondering how we are going to put four kids through college. You need an education to get a good job, yet I see us going into debt to get those degrees.”

Her son, Adam Culley, was considering WSU, but about three months ago the teen started looking at community college. Community college tuition has increased more than 25 percent since 2007, but it’s still a far cheaper option than a four-year institution for earning required credits.

“I’m looking at Spokane Community College, then transferring,” Culley said. “I’m planning to become a computer programmer.”

Tuition and fees for a full-time student at SCC are about $3,500 per academic year.

Lora Culley’s second-oldest child likely will go the same route, she said.

Enrollment at community and technical colleges went up 7 percent statewide between 2006 and 2010, according to the Higher Education Coordinating Board’s most recent data.

For former Washington resident Nick CastroLang, the answer was attending college in Idaho.

“Idaho is surprisingly affordable even for an out-of-state student,” he said. Tuition and fees at the University of Idaho are about $5,000 less than Washington public universities and his out-of-state status was waived.

“A lot of my friends decided to go to UI, even though it’s not a top school, because it’s cheaper,” CastroLang said. “A lot of my friends have talked about other schools they wanted to go to, but they just couldn’t afford it.”