Neil Armstrong, first man to walk on moon, dies at 82

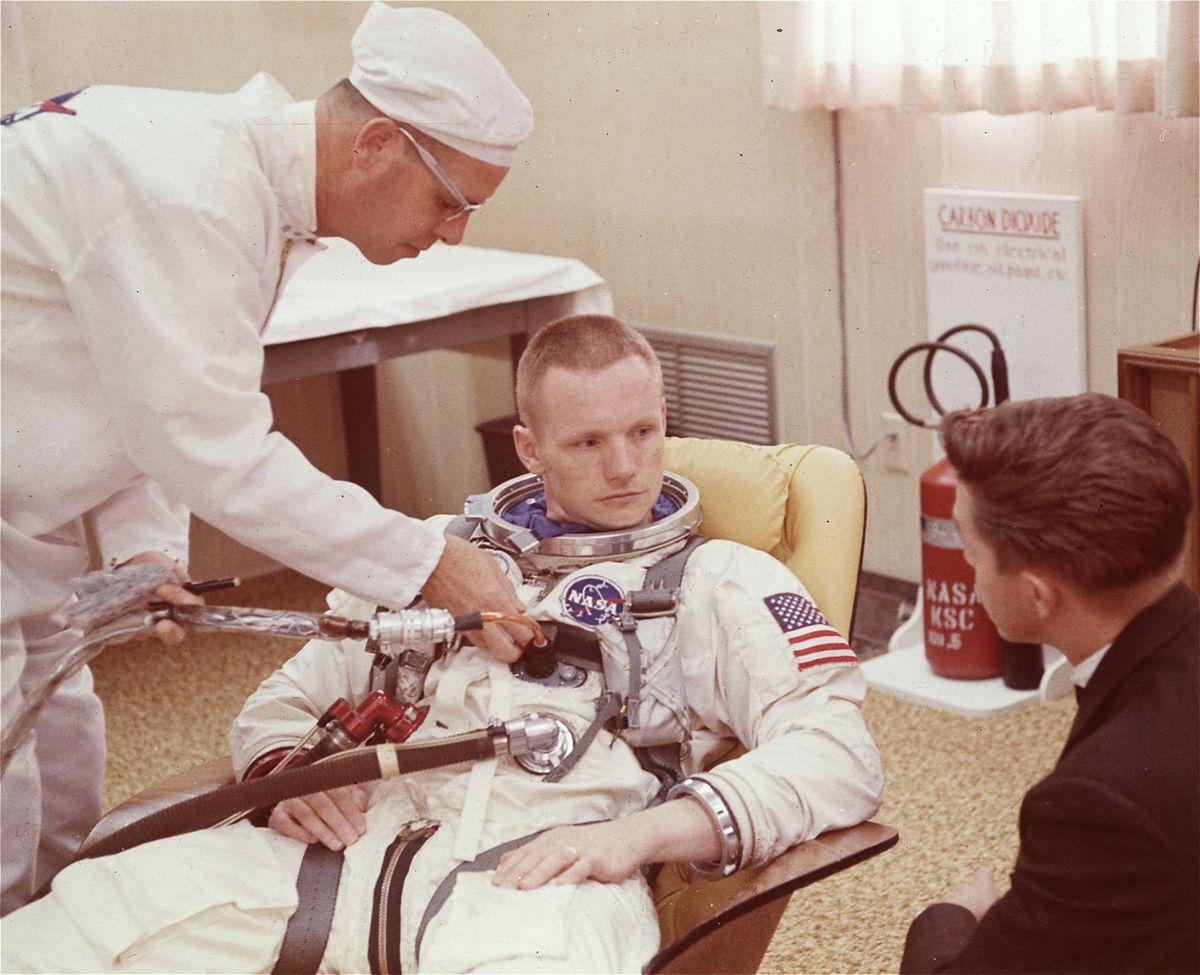

FILE - In this March 9, 1966 file photo, Astronaut Neil Armstrong is seated during a suiting up exercise Cape Kennedy, Florida, in preparation for the Gemini 8 flight. (Associated Press)

When Neil Armstrong became the first person to set foot on the moon, on July 20, 1969, he uttered a phrase that has been carved in stone and quoted across the planet: “That’s one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind.”

The grainy black-and-white television images of him taking his first lunar stroll were watched by an estimated 600 million people worldwide – and firmly established him as one of the great heroes of the 20th century.

Armstrong, who had heart surgery in early August, died Saturday in Cincinnati at 82, said NASA spokesman Bob Jacobs. The cause was complications from cardiovascular procedures, his family announced.

For the usually taciturn Armstrong, the poetic statement was a rare burst of eloquence, a sound bite for the ages that only increased his fame. He was never comfortable with celebrity he saw as an accident of fate, for stepping on the moon ahead of fellow astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin. The reticent, self-effacing Armstrong would shun the spotlight for much of the rest of his life.

In a rare public appearance, in 2000, Armstrong cast himself in another light: “I am, and ever will be, a white-sock, pocket-protector, nerdy engineer.”

History would beg to disagree.

In a statement, President Barack Obama said that when Armstrong stepped on the moon, “he delivered a moment of human achievement that will never be forgotten.”

And when Armstrong and his two fellow crew members lifted off from Earth in Apollo 11, “they carried with them the aspirations of an entire nation,” Obama said. “They set out to show the world that American spirit can see beyond what seems unimaginable – that with enough drive and ingenuity, anything is possible.”

In the years that followed the flight of Apollo 11, Armstrong was asked again and again what it felt like to be the first man on the moon. In answering, he always shared the glory: “I was certainly aware that this was the culmination of the work of 300,000 to 400,000 people over a decade.”

Yet how many other self-proclaimed nerdy engineers flew 78 combat missions as a Navy fighter pilot during the Korean War? Logged more than 1,000 hours as a test pilot in some of the world’s fastest and most dangerous aircraft? Or became one of the first civilian astronauts and commanded Apollo 11, the first manned flight to land on the moon?

His biographer, James R. Hansen, called Armstrong “one of the best-known and least-understood people on the planet.”

When asked to describe the astronaut in just a few words, Hansen told Ohio’s Columbus Dispatch in 2005 that Armstrong was “stoic, self-controlled, dedicated, earnest, hardworking and honest.”

Neil Alden Armstrong was born Aug. 5, 1930, on his grandfather’s farm near Wapakoneta, Ohio, and had a happy and conventional upbringing.

His civil servant father, Stephen Armstrong, audited county records in Ohio and later served as assistant director of the Ohio Mental Hygiene and Corrections Department. The family of his mother, Viola, owned the farm.

At age 6 he took a ride in a transport plane, then rushed home and began building model airplanes – and a wind tunnel to test them.

A good student, Armstrong was a much-decorated Boy Scout and played the baritone horn in a school band. But aviation always came first.

In 1945, he started taking flying lessons, paying for them by working as a stock clerk at a drugstore. On his 16th birthday, he got his pilot’s license but didn’t yet have a driver’s license.

Upon graduating from high school in 1947, he attended Purdue University on a Navy scholarship. By the time the Korean War started in 1950, Armstrong had been called to active duty.

After flight training, Armstrong was assigned to the carrier Essex, flying combat missions over North Korea. Although one of the Panther jets he flew off the carrier was crippled by enemy fire, he nursed the plane back over South Korea before bailing out safely.

Recognized as an outstanding pilot with a flair for leadership, he received three Air Medals before finishing his active duty in 1952.

He returned to Purdue and earned a bachelor’s degree in aeronautical engineering in 1955.

Within months, he was a civilian test pilot for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, which became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. He was soon stationed at Edwards Air Force Base in California’s Mojave Desert, chronicled by author Tom Wolfe as the home to pilots with “The Right Stuff.”

Aviators were closely scrutinized there, evaluated carefully as they pushed high-performance aircraft to “the edge of the envelope” and quizzed repeatedly about the scientific implications of their work.

“A lot of people couldn’t figure Armstrong out,” Wolfe wrote. “You’d ask him a question and he would just stare at you with those pale blue eyes of his.

“And you’d start to ask the question again, figuring that he hadn’t understood, and – click – out of his mouth would come forth a sequence of long, quiet, perfectly formed, precisely thought-out sentences, full of anisotropic functions and multiple-encounter trajectories or whatever else was called for.

“It was as if his hesitations were just data punch-in intervals for his computer.”

At Purdue, Armstrong dated a sorority beauty queen, Janet Shearon, and they were married in 1956. Children soon followed. A son, Eric, in 1957 and a daughter, Karen, two years later. The couple had a second son, Mark, in 1963, a year after Karen died of a brain tumor. True to form, Armstrong did not publicly address the tragedy.

By 1963, NASA was striving to fulfill President John F. Kennedy’s goal of beating the Soviet Union in the space race and putting an American on the moon before the end of the decade. Kennedy wanted some civilian astronauts, and Armstrong was one of the first.

In 1966, he made his first space flight, with fellow astronaut David R. Scott. Their ship, Gemini 8, was docking with an unmanned Agena rocket when a malfunctioning thruster sent the interlocked space vehicles tumbling uncontrollably.

Unperturbed, Armstrong disconnected the two vehicles, brought Gemini 8 back under control and made a safe emergency landing in the Pacific. NASA officials cited his “extraordinary piloting skill” and took note of his calm.

Two years later, a lunar landing training vehicle Armstrong was piloting suffered control failure just 200 feet off the ground. Armstrong ejected, parachuting to safety.

On Jan. 1, 1969, he was named commander of Apollo 11, the first manned spaceship scheduled to land on the moon. His crewmates were fellow space veterans Aldrin and Michael Collins.

Five months later, the massive Apollo 11 spaceship was nudged carefully onto the launch pad in Cape Canaveral, Fla., at Kennedy Space Center.

The vehicle was as long as a football field, tipped on end. It consisted of the command module Columbia, which would carry the three astronauts on their 238,000-mile journey and in which Collins would orbit the moon; the lunar lander Eagle, which would carry Armstrong and Collins down to the lunar surface; and a huge Saturn booster rocket to hurl the whole thing into space.

On July 16, 1969, Apollo 11 blasted off. Two and a half hours later, after an orbit and a half around Earth, onboard rockets fired to send the spaceship on its three-day trip to the moon. Once in lunar orbit, Armstrong and Aldrin clambered into the Eagle and descended toward the lunar surface, leaving Collins to circle above them.

The landing wasn’t easy. The lunar surface was rockier than expected, and Armstrong had to pilot the fragile craft horizontally until he found a safe, flat spot.

On July 20, 1969, at 1:04:40 p.m. Pacific Daylight Time, the small spacecraft came to rest gently near the moon’s dry Sea of Tranquility.

“The Eagle has landed,” Armstrong radioed back to Earth.

Six hours and 52 minutes later, as an onboard television camera sent grainy but stunning images back for the world to see, Armstrong became the first human to set foot on lunar soil.

His famous quote that would reverberate through time was actually missing a word, Armstrong said soon after returning to Earth.

As he gazed down at his footprint, the first made by a human on the moon, Armstrong said that he intended to say “one small step for a man” and thought that was what he had said. In a rare 1999 interview, he admitted he could not hear the “a” when he listened to the radio transmission as it traveled almost a quarter million miles back to Earth.

Aldrin stepped out of the Eagle a few minutes after Armstrong. The pair spent more than two hours on the lunar surface, collecting dozens of soil and rock samples, setting up seismic equipment, planting an American flag and taking photographs.

“Isn’t this fun?” the usually reserved Armstrong remarked jocularly at one point, patting Aldrin on the shoulder as they bounded about in the low lunar gravity.

As Armstrong and Aldrin climbed back into the Eagle, they left behind a plaque that reads: “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot on the moon. We come in peace for all mankind.”

Within hours, the Eagle had lifted off from the moon and rejoined the Columbia, and the three astronauts were on their way back to Earth.

On July 24, 1969, Apollo 11 splashed down in the Pacific about 950 miles south of Hawaii. To ensure they weren’t carrying any lunar organisms, the astronauts were quarantined for 18 days. President Richard M. Nixon waved to them through a window of their isolation chamber.

The nation saluted them on Aug. 13, 1969, when they appeared in a parade in New York City in the morning and another in Chicago in the afternoon. That night, they were honored by 1,400 people at a state dinner at the Century Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles. Nixon gave each of them the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

The public adulation eventually dimmed for Aldrin and Collins, who survive him. But not for Armstrong; whenever he made a public appearance, people clamored for his autograph.

At first he retreated for a couple of years to a NASA desk job in Washington. After earning a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering at USC, he returned to Ohio. For a decade, he taught aerospace engineering at the University of Cincinnati.

He bought a secluded 200-acre dairy farm near Lebanon, Ohio, and occasionally ventured into town for a quiet lunch at a local cafe. The town respected his privacy and he said he enjoyed the moderate physical work required on a farm.

When called by his country, he responded, serving in 1985 on the National Commission on Space and as vice chairman of the presidential commission that investigated the 1986 explosion of the space shuttle Challenger.

He continued to fly, piloting a light plane. He served on the boards of several large corporations and chaired AIL Technologies, an aerospace electronics firm on Long Island, N.Y., from 1989 to 2002.

And he surprised many observers when he made television commercials for Chrysler in 1979.

In 1994, Armstrong divorced his wife of 38 years. Shortly afterward, he married the former Carol Knight, a woman 15 years his junior, and receded further from public life.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by his two sons, a stepson, a stepdaughter, 10 grandchildren, a brother and a sister.

The closest Armstrong came to describing what the Apollo 11 mission meant to him was during a Life magazine interview several weeks before the flight.

“The single thing which makes any man happiest is the realization that he has worked up to the limits of his ability, his capacity,” Armstrong said. “It’s all the better, of course, if this work has made a contribution to knowledge, or toward moving the human race a little farther forward.”