Talk at federal, state levels alarms rural hospitals for future

They know they must participate in budget cuts

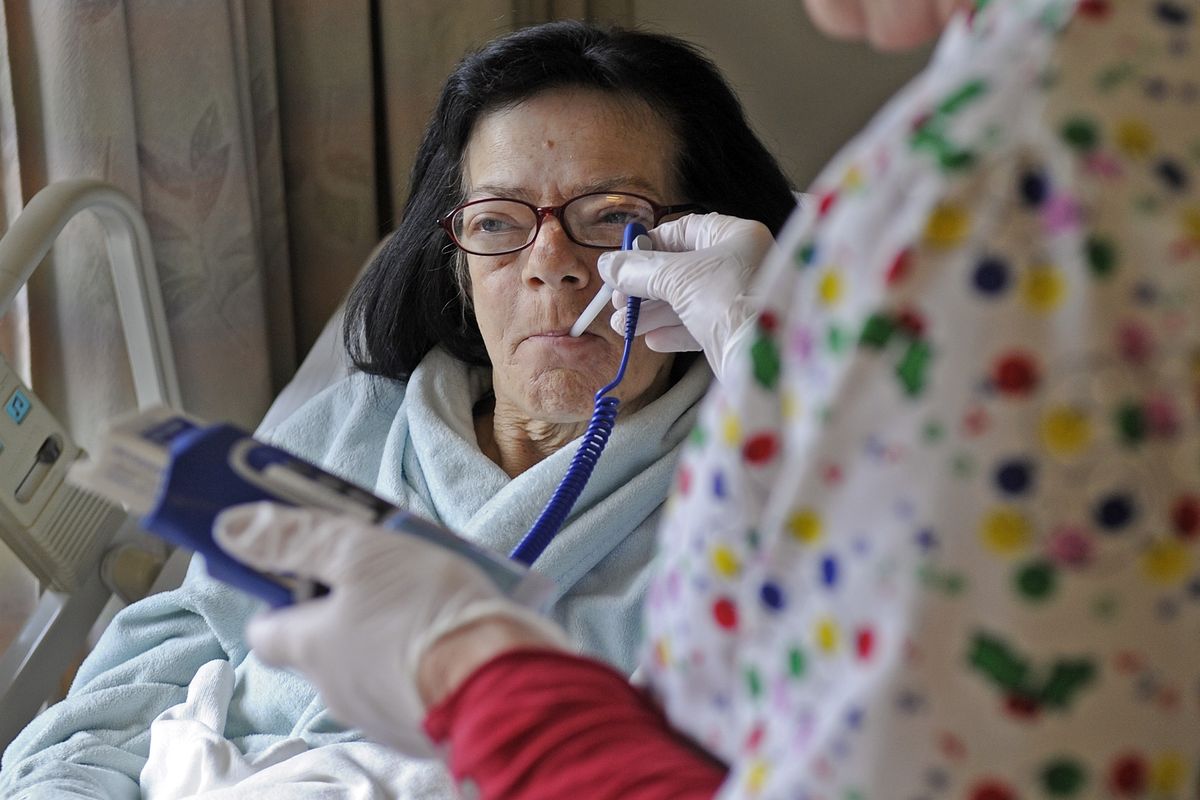

Terissa Norris has her temperature checked last Wednesday at Providence St. Joseph Hospital in Chewelah, Wash. Norris fears that cuts in health care will eliminate smaller hospitals like St. Joseph and she would be forced to travel to Spokane for health care. (Christopher Anderson)Buy a print of this photo

Many of Eastern Washington’s small hospitals are bracing for cutbacks as federal and state governments look to save money.

Consider Providence St. Joseph Hospital in Chewelah: On any given day perhaps nine of its 25 patient beds are occupied. Two of those patients might have private insurance. One might not pay the medical bill. The rest will be covered by government programs such as Medicare and Medicaid.

And yet the hospital has made money in four of the past five years, in part because rural hospitals receive richer payments from government than larger urban hospitals to care for proportionally higher numbers of the poor, elderly and uninsured who populate rural America.

It’s a bottom-line boost that has kept 38 hospitals in rural Washington afloat. But that extra money from Medicare and Medicaid is drawing the attention of budget cutters.

If proposals to retool and scale back the payments are adopted, up to half of these hospitals could be closed within a matter of years, say administrators and policy analysts.

Twice this year the federal government has pointed to its “critical access hospitals” program as ripe for change. The White House believes it can save $6 billion over the next decade by trimming the Medicare dollars it sends to these 1,300 hospitals stretched across the country.

A worse prospect for regional hospitals, however, is the continuing budget woes of state government.

The Washington Legislature is expected to consider a bill that changes the way it pays Medicaid bills submitted by critical access hospitals. The savings from HB 2130 to state taxpayers could reach $27 million a year.

Hospital supporters say such savings would translate into a double-whammy because the $27 million state cut would be accompanied by the loss of $27 million in federal matching funds, for a total loss of $54 million in Medicaid funding to Washington’s small hospitals.

“We’re talking about a throat-cut,” said Tom Martin, the chief executive of Lincoln Hospital in Davenport, who is pushing back against the possibility of cutting hospital funding.

The Davenport hospital is the only health care facility along U.S. Highway 2 between Spokane and Wenatchee. Physicians and nurses there mend broken bones from car accidents, treat people hurt in boating accidents on nearby Lake Roosevelt and sew shut wounds from farming mishaps.

Most often, though, the hospital and its network of clinics and nursing homes help the elderly fight pneumonia, recover from falls and cope with diabetes-related illnesses and other common problems.

“We care for the people of this community,” said Martin. “We’re the safety net. If we have to cut services, it’s going to have a severe and negative effect on people.”

State officials acknowledge the dire consequences of trying to shave $2 billion from the state budget.

“This is due to the horrible economic crisis we’re currently in,” said Sandy Stith, hospital finance officer for the state Health Care Authority.

“In looking for areas where we actually have the ability to make cuts at this point in time, they have become rather few and far between,” she said.

‘Necessary providers’

Congress created its critical care access program in 1997 following a wave of rural hospital closures, said Cassie Sauer, a spokeswoman for the Washington State Hospital Association.

Sen. Max Baucus, D-Mont., helped push the legislation through in large part to ensure people in far-flung places like small-town Montana could have reasonably close access to a hospital. It also ensured the elderly could stay in their hometowns rather than have to move to larger towns and cities for hospital care.

Under the law, hospitals at least 35 miles from another hospital would be reimbursed their actual costs, plus 1 percent, of caring for Medicare patients. Urban hospitals, conversely, are paid set amounts for specific treatments and services, which vary by location.

The trade-off required small hospitals to keep just 25 beds and limit the average patient stay to fewer than four days.

The plan began to work and small hospitals stabilized while still caring primarily for the poor and elderly on government programs.

In some instances, states began using the program to help almost all of their small hospitals gain entry, even if they didn’t obviously qualify. They did so by labeling such hospitals “necessary providers,” structuring guidelines that enabled more small hospitals to slip into the more-generous payment program even if they were in close proximity to other hospitals.

Of the 38 critical access hospitals in Washington, for example, only seven meet the federal government’s original distance criteria. But they all meet at least one “necessary provider” criterion outlined by the state, which can include high numbers of poor and elderly patients or financial vulnerability that would leave rural patients without nearby 24-hour emergency room care.

Not much wiggle room

Last week Terissa Norris recovered from a blood transfusion at St. Joseph Hospital.

It was the second hospital trip in a year, brought about by exposure to black mold in a building that had been flooded. She wouldn’t go anywhere else.

“I love this place,” said Norris, 57.

Planted by Catholic nuns 80 years ago between hospitals in Spokane and Colville, St. Joseph is an important mainstay of Chewelah’s quality of life and economy.

“A lot of us up here don’t want to go to the city, Spokane, for medical treatment,” Norris said. “It’s too expensive. We’d have to drive down there. Our families would have to travel too far for visits.

“It would be a very severe, bad mistake if something were to happen to this hospital.”

St. Joseph is now owned by Providence Health Care, which also runs the hospital in nearby Colville as well as Providence Holy Family Hospital and Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center in Spokane.

If deep cuts in Medicare and Medicaid payments undercut St. Joseph’s financial position, it could prompt Providence to begin a review. The hospital system would weigh many factors and meet with community leaders before deciding whether to continue operating the hospital at a loss, reduce service, combine with another hospital or close. Providence closed its hospital in Deer Park in 2008.

Smaller hospitals need the better payments from Medicare and Medicaid because they don’t have the ability to pass on costs incurred from bad debts and low reimbursements to patients with private health insurance, a practice commonly called cost shifting, said Bob Campbell, who oversees St. Joseph. Nor do small hospitals have enough patients to spread out and absorb the high, fixed costs of meeting quality standards.

Campbell said small hospitals know that they must participate in budget cuts.

“But to do this within one year? A 50 percent cut to Medicaid payments? And not come up with a strategy to sit down with us and say, ‘What can be done?’ It’s too much,” Campbell said.

“We know conversations need to be had during these tough budget times. Should there be two hospitals in Chewelah and Colville? That’s a legitimate question,” he said. “But give us time to do the analysis, talk to the community and help us decide if we can then continue to provide top medical care in these communities.

“Let’s go through a process that’s rational rather than just draconian cuts.”

When it comes to raising revenues, however, small hospitals and their communities are torn. The half-cent sales tax increase floated by Gov. Chris Gregoire received a chilly reception in Davenport because it wouldn’t offset proposed cuts to critical access hospitals, said Deral Boleneus, a Lincoln Hospital board member and past Lincoln County commissioner.

The hospital district supporting Lincoln Hospital collects taxes each year to support building projects and technology purchases. Hospital administrator Martin is expected to manage an operating budget that runs near break-even.

It’s an arrangement that has helped the hospital enjoy continued support from voters.

“What we’re opposed to is an all-cuts budget,” said Sauer of the hospital association. “What we can agree to at this point is a blend of mild cuts, finding more efficiencies in state government, and increases in revenue, but not necessarily tax increases as they have been proposed.”