Modern train cars have made hobo lifestyle a thing of the past

A BNSF freight train rolls through the Marshall area just south of Spokane. Trains are harder to jump since the design of the individual cars has become more specialized and streamlined. (CHRISTOPHER ANDERSON chrisa@spokesman.com Below: File photos archive)

Gus Melonas, regional spokesman for BNSF Railway, grew up in the early 1960s in a railroad station house in Wishram, Wash.

He and his twin brother walked to the park near their house to visit with the “hobos” – the men who rode the rails and lived in camps between journeys.

“The hobos would give us Twinkies every day,” Melonas recalled. “They would tell train stories.

“There was never any trouble with the hobos. They were always friendly.”

When Melonas followed in his father’s – and grandfather’s – footsteps and took a job with the railroad in the mid-1970s, he ran into hobos all the time, on the trains and in the camps.

But now?

“I cannot recall the last time I actually saw a person on a railcar,” Melonas said.

The hobo culture is pretty much dead, except in literature, film and people’s imagination.

What the heck happened?

Hobos: A brief history

Hobos surfaced in U.S. history in the mid-1800s, at the same time railroads emerged as a major mode of transportation in the United States. After the Civil War, displaced veterans rode the rails in search of work and new lives.

By the early 1900s, one New York newspaper estimated that about 700,000 transients, almost all men, regularly rode the rails.

During the Great Depression, hobo numbers soared as men – and families – moved around the country in search of work.

In 1937, a Utah law enforcement official, exasperated with the 50 to 100 hobos passing through his town each day, suggested they be corralled into work farms for 90 days. His suggestion made news throughout the country, including in The Spokesman-Review.

The men who rode the rails, however, were considered a better breed of “bum,” because they were often willing to work for food.

Bob Grandinetti, a retired police Spokane police officer, remembers his mother and other East Spokane neighbors giving hobos sandwiches.

“If you had yard work, they’d do it,” he said.

Train hobos, romanticized in film, book and song, became symbols of freedom and adventure, and not just for men down on their luck.

In the mid-1970s, Melonas met a professor from Syracuse riding the rails for kicks.

“Another was a tennis professional who caught a ride from Southern California for a tennis tournament in Seattle,” he said.

But scrape off the thin veneer of glamour, and you’d quickly find the grimness.

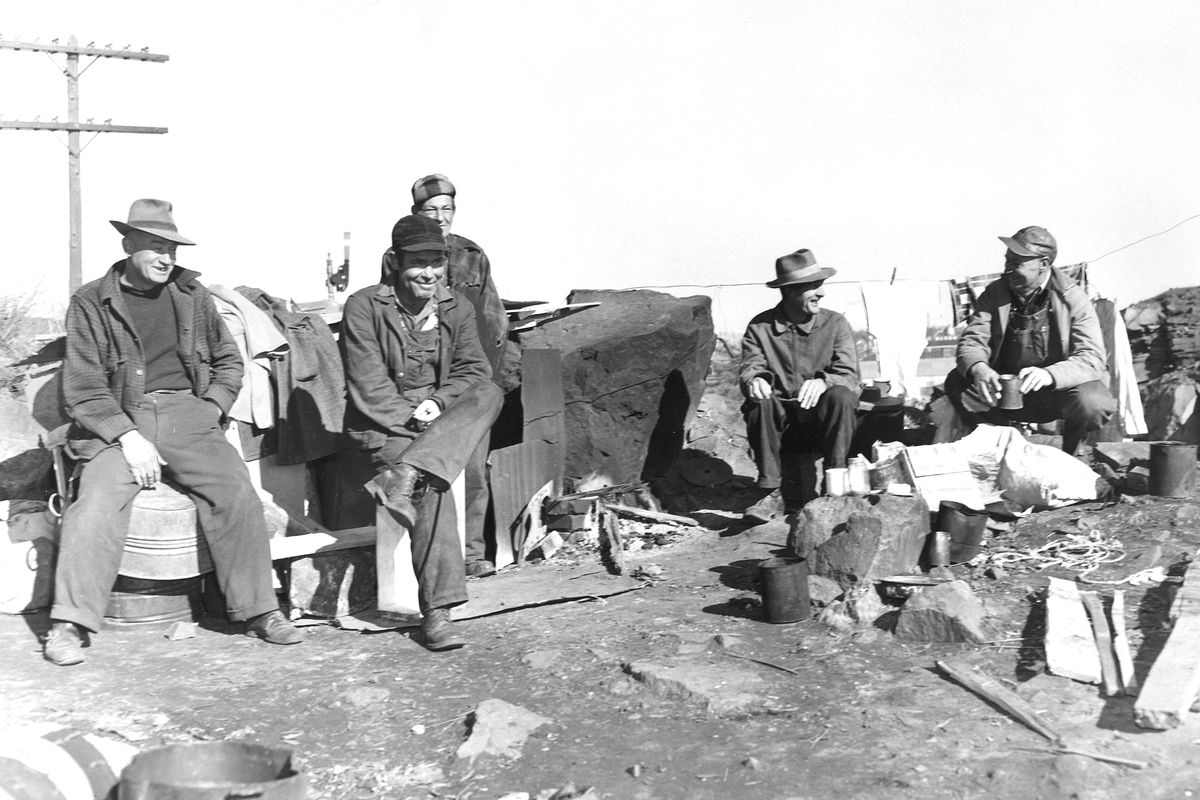

In 1958, Spokesman-Review reporter Dorothy Rochon Powers interviewed men in hobo camps under Spokane’s railroad bridges.

She wrote: “The wracking loneliness is there … and the filth, and the rusty tin cans, and the ramshackle windbreaks, built of discarded boxes.”

Dave Wall first went to work for Spokane’s Union Gospel Mission 23 years ago, when it was still common for hobos to come to the mission for meals.

One day he met a man who couldn’t walk. He was “oozing from the groin area,” Wall said.

While riding the train, he had wiped himself with dirty insulation found in the boxcar. An infection followed. Eventually, gangrene set in.

Still, trains kept up their siren calls.

A dozen years ago, while Wall talked to a man who was in the mission’s long-term recovery program, the man heard a train nearby and said: “It’s calling me, Dave. I don’t know if I can stay.”

He didn’t.

Hobo culture: the demise

Dick Bosse, a retired railroad worker, built his home a rock’s throw from a train crossing near Sandpoint. He sits in his sun porch and watches about two dozen trains go by each day.

He has lived there for eight years and has never seen a hobo riding on or in a car, because railroad cars are no longer rider-friendly.

Hobos in the past hopped onto open, flat cars. Or they nestled into boxcars, after easily prying open the doors.

Now many of the cars are “intermodal container cars,” transported by ship, truck and rail and sealed as tight as tuna cans.

Other railcars “are closed and refrigerated cars,” Bosse said. “They can’t get into them. They have special locks.”

Almost all railcars lack surfaces to grab onto or space to sit down in. Some are even nicknamed “suicide cars.”

Another reason for hobo demise? The change in hobo culture.

In the 1990s, Grandinetti noticed that the benign hobos of his childhood had disappeared. The new rail riders often formed gangs who robbed and sometimes murdered.

With the backing of his police department, and city officials, he orchestrated a campaign to rid Spokane of train hobos, especially the Freight Train Riders of America who drank fortified Thunderbird wine as part of their hobo code.

When the city passed an ordinance banning the sale of fortified wine in areas close to the railroad tracks, many of the Freight Train Riders skipped Spokane in their rail adventures.

Also in the 1990s, railroad companies throughout the United States cracked down on trespassing. After Sept. 11, even more crackdowns followed, because of terrorist concerns.

“In my career, the biggest change has been the emphasis on safety,” Melonas said. “Even crew members (can’t) hop on and off moving trains.”

Last weekend, Britt, Iowa, hosted the National Hobo Convention, a mainstay there since 1900. Genuine train hobos attended throughout the 20th century, but in the absence now of real hobos, the event has gone country-fair mainstream.

For instance, the souvenirs for sale included refrigerator magnets and golf balls – two items you’d never find in a hobo’s knapsack in our country’s king-of-the-road past.