Veterans Court weighs stress of war service

Innovation, second in state, pursues treatment options for criminal behavior

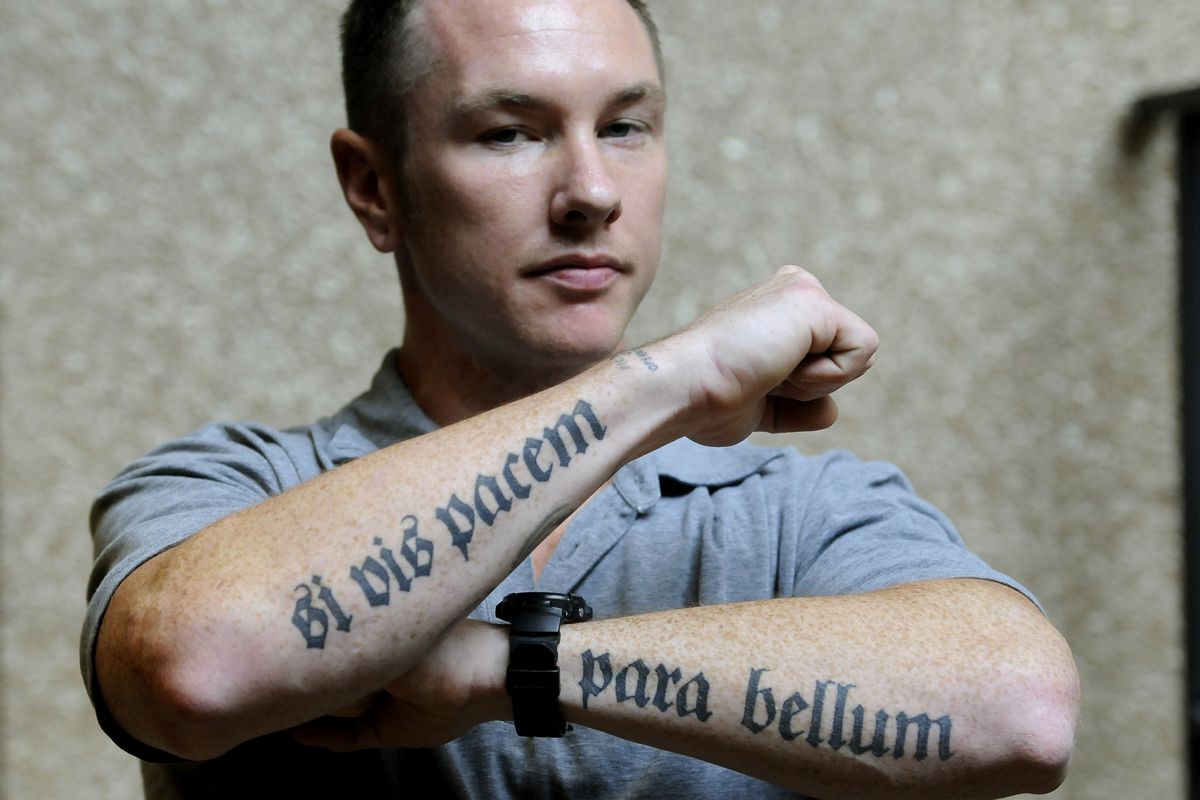

Iraq war veteran Carl Jacobson, 26, appears before Judge Vance Peterson on Thursday in the Public Safety Building in Spokane. Peterson, a retired Army Reserve officer, led the effort to establish Spokane County’s Veterans Court. (Dan Pelle / The Spokesman-Review)

After surviving 15 months in one of the most dangerous places on Earth, Iraq war veteran Carl Jacobson thought he could cope with just about anything civilian life had to throw at him.

Jacobson realized he was wrong the day he learned that his beloved former platoon leader had been gravely wounded by an enemy sniper.

“It broke me down,” Jacobson said. “No matter what comes your way, it’s crucial to any soldier to avoid losing control. You can’t lash out.”

Jacobson was arrested in July on a domestic violence charge after breaking the door of the north Spokane apartment he shares with his girlfriend and her two young children.

The former Army sergeant could have been convicted of third-degree malicious mischief last week, but instead he received a “stipulated order of continuance” from Spokane County District Judge Vance Peterson on the first day of Veterans Court.

If Jacobson completes a two-year counseling program under the terms of his continuance, the charge will be dismissed.

He was one of 13 veterans and active-duty soldiers answering misdemeanor or gross misdemeanor charges in Peterson’s courtroom on Thursday.

Four received stipulated orders of continuance, including one National Guard soldier whose felony charge was reduced to a misdemeanor. Eight had their cases delayed. One, who was in violation of the terms of probation, had his probation reinstated.

Two of the veterans appearing in court on Thursday were women, one accused of driving under the influence and another accused of fourth-degree assault.

There are other therapeutic courts – most notably Spokane County Superior Court’s Adult Therapeutic Drug Court and Spokane County District Court’s Mental Health Court – designed to divert defendants from the traditional criminal justice system into rehabilitative services. But Veterans Court is the first in Spokane County, and only the second in the state, designed specifically for military veterans or active-duty soldiers. Thurston County began a veterans court last July.

Veterans courts are part of a growing movement that began in Buffalo, N.Y., to divert offenders into treatment for psychological problems resulting from military service.

The courts are prompted by a realization that many soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan – conflicts in which there are no traditional fronts and a constant threat of violence – may suffer from post-traumatic stress, traumatic brain injury, substance abuse or other behavioral health conditions.

The Associated Press reported in May that there are 72,000 incarcerated veterans in the United States and that veterans account for about 10 percent of the population with criminal records.

The effort to establish Spokane County’s Veterans Court was led by Judge Peterson, a retired Army Reserve officer who coordinated with the Spokane Veterans Affairs Medical Center, the prosecutor’s and public defender’s offices, the probation department and other legal, military and social service agencies.

The formula has proved successful for Spokane County’s Drug Court, which deals with both mental health and substance abuse issues, said presiding Superior Court Judge Maryann Moreno.

Since 1996, Drug Court has graduated 475 defendants who have a recidivism rate of 22 percent – compared with national data that show felons with addictions left untreated reoffend at a rate of 70 percent to 80 percent.

But unlike Drug Court, which has an annual budget of about $1 million, 85 percent of which goes to treatment and recovery support services, Veterans Court so far has no specific funding allocated to it.

That’s largely because veteran offenders nearly always qualify for VA health services.

“The VA will provide the vast majority of the counseling,” said Paul Nicolai, substance abuse program coordinator at the Spokane Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Deputy prosecutors, public defenders and probation officers have volunteered to add the veteran dockets to their workloads, Peterson said.

In addition to counseling, offenders will be required to attend at least four monthly forums in which veterans will discuss relevant issues. For each forum attended, the offender will have one month knocked off the time he or she has been ordered to spend in the program.

Peterson’s plan goes even further, assigning a veteran mentor to guide the offender through the court-ordered program.

“A lot of these guys miss comradeship and get in trouble because of it,” Peterson said.

The judge envisions veteran offenders being put in touch with other services as well, including food and housing resources, employment counseling and legal advice for those who also face civil court issues such as child support.

“We have the ability to take people who might be felons and pre-empt them,” Peterson said.

But while he and others who have worked to make Veterans Court a reality are willing to give veteran offenders the benefit of the doubt, Peterson said they are not prepared to give anyone a free ride because they served in the military.

“We are not going to reinforce a failure,” Peterson said. “If they don’t comply, we will cut them loose. We don’t want jerks in the program.”

Critics of veterans courts argue that the American justice system should single no one out for special treatment.

However, Breean Beggs, former chief catalyst for the Center for Justice in Spokane, favors therapeutic courts, which recognize that approaches to changing behavior need to be individualized to fit the offender.

“Simply locking people up without considering what’s the most effective way to keep them from offending in the future is a mistake,” Beggs said. “Simply building new and larger jails has pretty much bankrupted us.

“The psychological wounds of veterans are unique,” Beggs said, “and the intervention is probably unique as well.”

Veterans Court was conceived with soldiers like Jacobson in mind.

The 26-year-old former sergeant was raised in Springdale, Wash., and attended Rogers High School in Spokane.

He served in Taji, Iraq, with the 1st Cavalry Division, which was assigned to secure the main supply route north of Baghdad, including a half-mile of highway known as “the gantlet” for the high number of bombings that occurred there.

Jacobson said his unit was hit repeatedly by roadside bombs, known as improvised explosive devices, and he said he was blown out of his vehicle twice.

He lost more than one friend in Iraq, including his best friend from basic training, Nicholas Greer, from Monroe, Mich., who was killed by a sniper in 2005. Jacobson bears a tattooed dedication to Greer on his right wrist.

Jacobson, a marksman, was assigned to provide security for his lieutenant, Matthew Burch, in 2007. When he found out Burch had been shot in the abdomen this summer, Jacobson lost control of his emotions.

“He said, ‘I should have been there, I could have saved him,’ ” recounted Teresa Queen, Jacobson’s girlfriend.

Jacobson’s lawyer, Tim Note, a candidate for District Court judge, said he has seen a disproportionately high number of veteran defendants during the past five or six years, facing charges related to alcohol, domestic violence or assault.

“A lot of these guys are coming back with issues and perceptions that if they ask for help they will be viewed as weak,” Note said. “Some have seen a lot of horrific things. They suppress, suppress and suppress, and then they have a blowup.”

He hopes Veterans Court will get them the help they need.