Release nears for foster mother blamed for starving child

Carole DeLeon served half her sentence in 7-year-old’s dehydration death

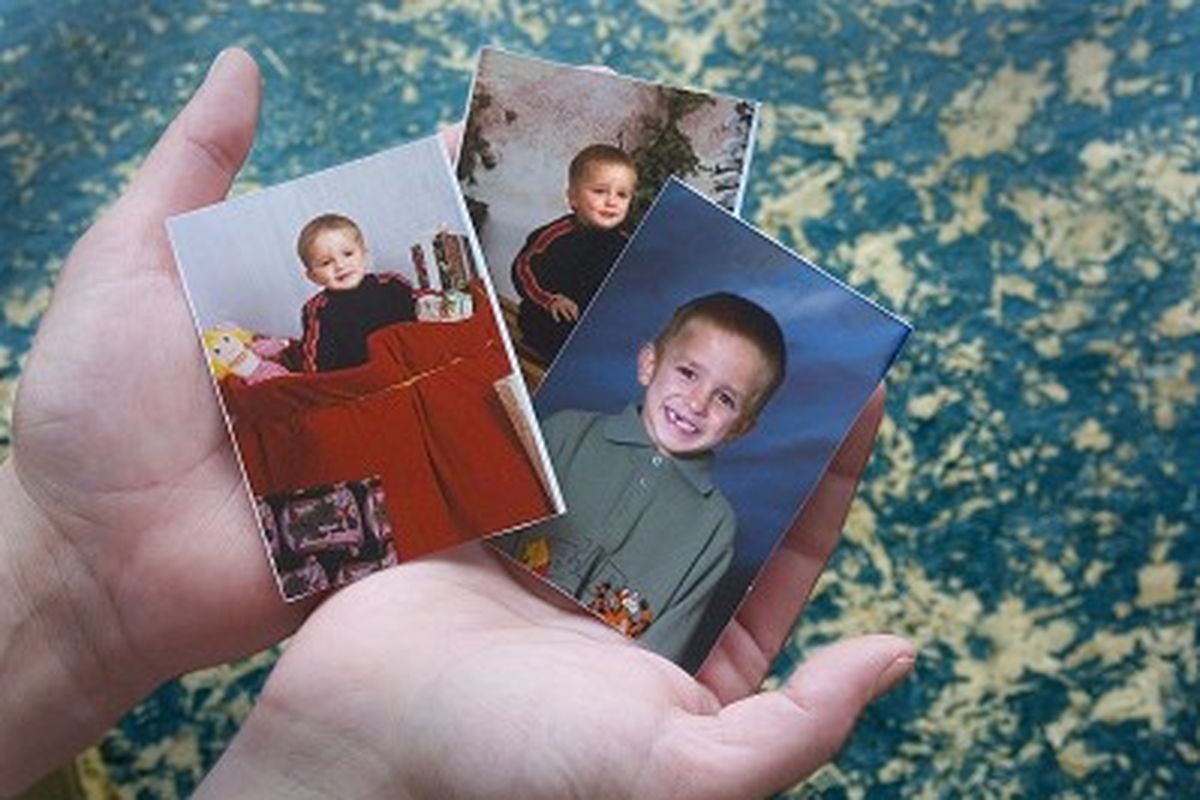

Tyler DeLeon at age 5, at a picnic with his mother. (File / The Spokesman-Review)

Carole DeLeon, the foster mother blamed for starving Tyler DeLeon to death, gets out of prison Wednesday after serving about half of the sentence she received in a 2007 plea agreement.

DeLeon, 55, has lost all parental rights of the other adopted and foster children who were in her care. And she did not contest a motion brought by attorneys to make sure she receives no part of a settlement with the state concerning its failure to protect Tyler.

But the legal fight over who failed Tyler is far from over.

“I truly don’t believe she could spend enough time. But no time frame from a judge or jury could ever bring Tyler back,” said Jerry Taylor, who recently retired from the Stevens County Sheriff’s Office and who led the DeLeon investigation. “I believe we did the best we could about getting her stopped.”

Tyler died on Jan. 13, 2005, the day he turned 7. The autopsy showed he weighed only 28 pounds, but his body was cremated before law enforcement began investigating. Because the autopsy only listed dehydration as the cause of death, Stevens County Prosecutor Tim Rasmussen offered DeLeon a deal to plead to two counts of criminal mistreatment to Tyler and another boy in her care.

Rasmussen originally charged DeLeon with homicide by abuse, which carries a potential sentence of life in prison. To the lesser charges, she entered an Alford plea, admitting no guilt but acknowledging she could have been found guilty based on evidence presented in court.

“My decision was difficult, but it was the right decision,” said Rasmussen, whose call prompted picketers to protest what they considered DeLeon’s lenient sentencing. “Because of the plea, all the remaining children were able to have her parental rights terminated. They, to my knowledge, are being loved and thriving with other families.”

DeLeon turned down a recent request by The Spokesman-Review to be interviewed at Pine Lodge Corrections Center for Women in Medical Lake. Her criminal attorney, Carl Oreskovich, could not be reached Monday for comment.

DeLeon’s father, Joe Silva, reiterated his belief that his daughter is innocent. “If the people who are still sitting here saying my daughter is responsible for my grandson’s death … would have gone ahead and looked at all the information the county and state had … they would know my daughter was not guilty of anything,” Silva said. “She’ll be home Wednesday. That’s the main thing. She survived the ordeal of prison life.”

While her release essentially ends the criminal side of the case, a civil case proceeds against Dr. David Fregeau, a DeLeon family friend and the boy’s primary care physician, and Sandra Bremner-Dexter, who was Tyler’s psychiatrist. Fregeau, his attorney and Bremner-Dexter’s attorney were not available late Monday for comment.

That civil case is on hold until the Washington Supreme Court decides the scope of possible damages and whether medical care providers are exempt from a state law that makes it mandatory to report child abuse, said Seattle attorney Tim Tesh. He previously helped win a $6 million settlement from the state Department of Social and Health Services for the children who were placed under DeLeon’s care, including $180,000 to Tyler’s estate. “It doesn’t make a lot of sense,” Tesh said of DeLeon’s release from prison after three years. “But my job is not to prosecute Carole DeLeon. It is to go after those who were civilly responsible … for allowing her to have the care of these kids in the first place.”

Tyler’s story began in May 1998 when the state placed the 4-month-old boy in a home where he never should have been. DeLeon lied in 1996 on her application to become a licensed foster parent, state records show, when she failed to disclose previous actions taken by the state against her, including the removal of a foster child who alleged that DeLeon in 1988 tied her up in the basement and regularly denied her food and water.

The state inadvertently destroyed the records documenting those allegations as part of routine file maintenance. Copies of those files were found only because a Stevens County deputy remembered that he had saved them.

After adopting Tyler in 2000, DeLeon repeatedly warned school officials to limit his food and water intake and to make sure he didn’t drink water out of the toilets, court records state. But a later state investigation couldn’t find any medical documentation supporting DeLeon’s claim that Tyler had eating or drinking disorders, the records say.

DeLeon was working as a paralegal at the U.S. attorney’s office when Tyler died. Silva said he doesn’t know what his daughter, whom he said other Pine Lodge inmates knew as “the church lady,” is going to do for a job.

“Whenever inmates had a problem, they wanted to talk to the church lady,” Silva said. “She’s quite a girl.”

Taylor, the retired detective, said Silva and several others were part of layers of failure that allowed the abuse to take place.

“It’s a shame (DeLeon) didn’t protect little Ty the way her father protected her,” Taylor said. “When that lady’s life is over, I strongly believe she will answer to some higher person. Then and only then is she probably going to have to pay.”