Writing, therapy help Iraq vet cope

Kenny McAnally is dealing with flood of emotions he carries from the war

Kenny McAnally served as a combat engineer in Iraq.Photo courtesy of Kenny McAnally (Photo courtesy of Kenny McAnally)

The New Year’s Eve party was at a friend’s Coeur d’Alene home, and Kenny McAnally had gone outside for a smoke.

Suddenly, fireworks began exploding all around him, and the combat veteran was back in Iraq, with no weapon, no backup and no one around who seemed to care. Screaming and crying, he covered his head with his arms and walked in circles as his panicked wife, Christy, begged him to tell her what she could do. Nothing, he said. He didn’t want anyone to touch him, to be near him, to help him.

That was on the last night of 2006, and it was the McAnallys’ first real glimpse of how the year Kenny spent in Iraq as a combat engineer had affected him. There was a bit of chaos every day, the 25-year-old said. Bodies blown apart in the street. Dogs with human flesh in their mouths. A helicopter carrying his friend Troy away in a body bag while McAnally saluted.

“You know when the dude is looking for his arm in ‘Saving Private Ryan’?” McAnally asked, his eyes filling with tears. “He’s on the beach and he’s looking for his arm and he grabs his arm? Um, that’s almost what it was like. That is really, really close.”

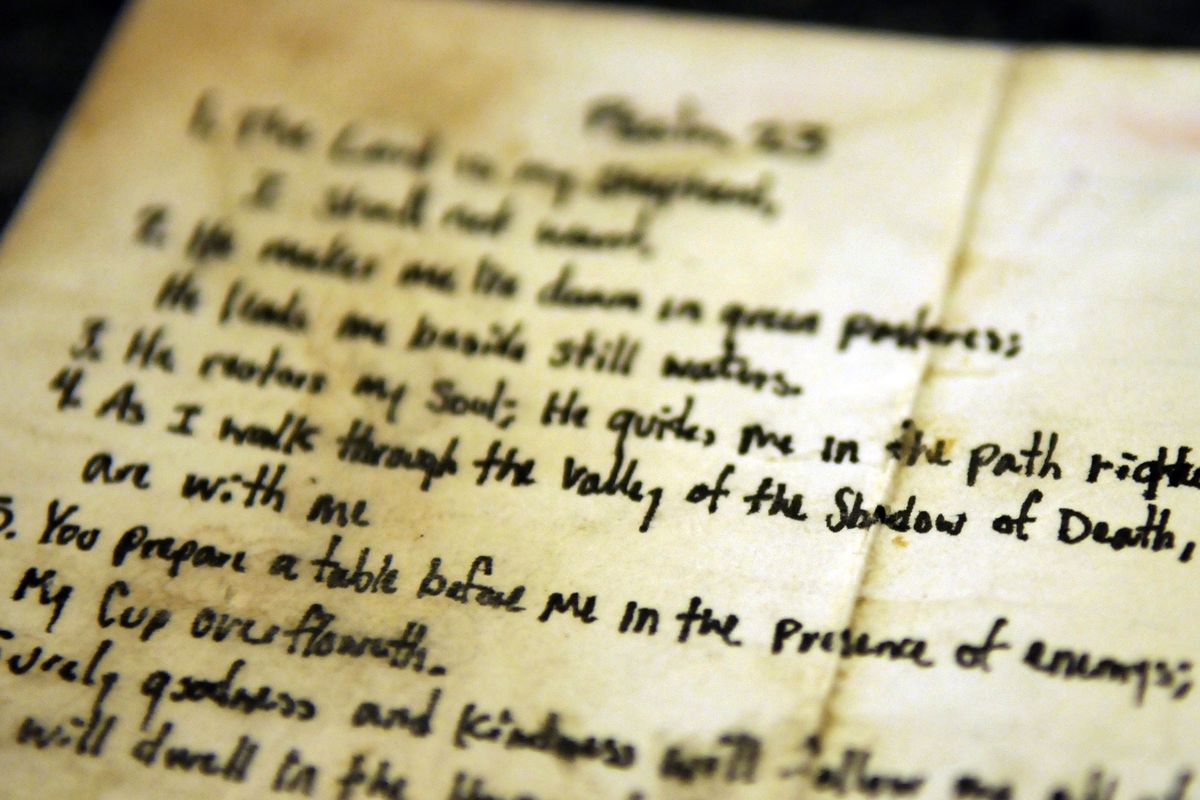

McAnally carried those memories for a year with no outlet, until a writing assignment for a North Idaho College class unexpectedly began to release them. It seemed harmless – write a descriptive story – but what poured out of him left him bathed in sweat and crying uncontrollably.

His writing described his worst day, the one that yanks him from sleep, gasping for air. Some 30 Iraqi National Guardsmen in the camp next door were hit in a mortar attack and he rushed to help. He looked into the eyes of a dying man as he tried to stop the blood pouring from the man’s side and leg. He prayed to God that the man would live, only to be told he was already dead.

“I can still hear those men, lying in the sand, bleeding to death, pleading with their God,” he wrote. “Screaming at him. Begging to live another day.”

Seeing the memories on the page in front of him convinced McAnally of something his wife, a social worker, had been advocating for months: starting therapy. In August 2009, two years after leaving the service, McAnally began therapy at Spokane’s VA Medical Center. He has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and has a disability claim pending with the Department of Veterans Affairs.

“I’ll never be cured. It’s not a curable condition. It’s the human condition, for a soldier,” McAnally said. But, he added, “I’ll be able to talk about it. And I think being able to talk about it is as cured as you can get.”

His VA therapist, Dawn Gray, said McAnally is among the veterans who can expect to improve because he’s worked so hard at therapy. “He’s made excellent progress,” said Gray, also an Iraq combat veteran. “He’s one of those people who are going to have measurable significant benefits from this.”

McAnally is part of a new generation of combat veterans returning home and attempting to resume normal lives since the wars began in Iraq and Afghanistan almost a decade ago. Some 12 percent of returning Army veterans exhibit signs of PTSD, a number that rises with additional deployments, according to the Brookings Institute’s “Iraq Index.”

A Defense Department study found that 16 percent of soldiers and Marines returning from Iraq exhibited symptoms of PTSD, but 60 percent of those were unlikely to get help, fearing commanders or fellow troops would treat them differently, the San Francisco Chronicle reported in 2005.

McAnally, however, has found his path to healing – through therapy, writing, his wife’s support and a new purpose in life. He’s studying to become a social worker, like his wife, with hopes of helping heal combat veterans like himself. And he thinks his memories could one day become a book.

“Writing what happened down makes it so you don’t have to think about it every day,” he said. “Helping someone else do that would, I mean, that would be awesome. It would free them.”

Christy McAnally, who regularly counsels veterans in her work at Kootenai Medical Center, said reading her husband’s writing made her realize how many people he could help.

“You’re putting a voice to what happened,” she said. “Not everybody has that gift, and not everybody has that ability. There’s something that needs to be pulled out here. It doesn’t help to keep it in. It doesn’t help anyone.”

Headed for war

McAnally was born and raised in Coeur d’Alene, which he calls the greatest place in the world. His family always attended the July 4 parade, and several members served in the Army. McAnally was 18 years old in 2003 when he enlisted in the Army, six months before graduating from Lake City High School. He figured it would be a good way to see the world, pay for college and serve his country.

He went to Missouri, then Germany. He turned 19 during basic training and selected combat engineering as his job. The mission in Iraq was route clearance, which mostly entailed searching out and blowing up the improvised explosive devices uncovered along Iraq’s roads. He thought that sounded fun.

“Have you seen the movie ‘The Hurt Locker’?” he asked. “We were the guys before those guys. We wrote the training manual on route clearance.

“It’s like sitting on a bomb the entire time.”

But spending every day combing the roads of Iraq at 5 miles per hour looking for footsteps in the sand, wires or anything unusual never guaranteed they’d find them all. The day they missed one, American soldiers died. In his writing, McAnally says he feels certain he saw the bombers driving away, blank stares on their faces.

“I should have been looking down. I feel in some way that I am responsible for their deaths. (The) men bled to death in the sand while their friends, brothers, watched hopelessly; and following us, they thought it was clear,” he wrote. “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.”

McAnally came home for a two-week leave in August 2005, two months before going to Iraq. That’s when he reconnected with Christy, with whom he’d worked at a Coeur d’Alene restaurant years before. He knew instantly he wanted to spend his life with her. She e-mailed him every day he was in Iraq, and he slogged through mud to call her every night from the camp phone center.

On his next leave, in March 2006, he was so grateful to be home, she said, he just wanted “to have normal. That’s what we talked about. It wasn’t these huge trips or those things. It was, ‘I can’t wait to make dinner with you, I can’t wait to wake up with you, I can’t wait to take a walk together, to see you in person.’ Normal stuff, stuff that would otherwise be taken for granted.”

The night before he returned to Iraq, Kenny and Christy stayed up all night. Putting him on the plane was the hardest thing she’s ever done, she said. After he boarded, she walked to the parking lot, got into her car and cried.

“I had no clue what was going on,” said Christy McAnally, who is 27. “I knew it was bad – I mean, nobody wants to send their loved one over there. And yet he had this sense of duty. It was just, ‘This is what I have to do. This is my job.’ And I just felt … helpless.”

Their phone calls were frequently interrupted with calls of “incoming,” and Kenny would have to leave immediately.

“And some days I wouldn’t get calls for a few days, and then you just hope and pray that everything’s OK,” she said. “I remember we’d always try to talk about the future and good things.”

On Nov. 1, 2006, he finished his tour of duty in Iraq. Ten days later, he returned home and married Christy in a friend’s backyard on Lake Coeur d’Alene. He took a two-week leave from his final year of service in Germany to return home for Christmas a month later, then was home permanently on Aug. 17, 2007. That’s also the day he quit smoking.

“I quit doing things that were going to get me killed,” he said.

The aftermath of war

Ten days after arriving home, McAnally was sitting in an NIC classroom. Culture shock hit hard: He couldn’t believe how disrespectful students were toward their teachers. Complaints about mundane things like parking made him angry. He found his classmates spoiled when compared with the poor but happy Iraqi children he’d seen every day.

McAnally was still the laid-back joker he’d always been, his wife said. And he was full of plans, like going to school and starting a family. But he was also more responsible, more grown up, and more aware of the world’s darker side. He became short-tempered and regularly repeated that no one here understands what’s going on “over there.” He made few friends yet talked every day to his buddies from the war.

“Those guys I went to war with,” he said simply, “I was ready to die with.”

His friend Allan Fix, of Garfield, N.J., echoed those thoughts: “I’m an only child, and Kenny’s the closest thing to a real brother I’ve ever had.”

One Memorial Day, McAnally was working at Hudson’s Hamburgers and a man walked in with a T-shirt depicting flag-draped coffins. “And it said, ‘Hey Mom, I’m coming home,’ ” McAnally said, his eyes filling with tears. “And it was on Memorial Day.”

He’d see a pile of trash on the side of the road and yell “BOOM!” or jerk the car to the side. When his car slid on the ice returning from snowboarding at Silver Mountain, he felt instantly out of control. Writing made him realize therapy might help, but he procrastinated because “talking about this kind of stuff sucks.”

Finally, one day, his wife drove him to the VA Medical Center in Spokane and said, “We’re going inside.”

They had talked about therapy, and from her work with veterans, Christy McAnally believed the VA could help her husband.

“He just had these instances when he couldn’t control his emotions and he didn’t know why,” she said.

Road to recovery

McAnally’s been in therapy for more than a year now and has continued to write. He has 75 pages of what might one day become a book. Lately, he’s been writing funny stories, remembering the humor that helped him cope with being in Iraq.

He still has flashbacks, but therapy has helped him to think more rationally, he said. When he and his wife boarded a plane for a belated honeymoon trip to Hawaii, he thought, for a brief moment, that terrorists were on board. Then he challenged his thoughts: “Really? In Spokane?”

He doesn’t have as many angry outbursts and focuses on what he wants to do in life, as opposed to “this happened to me. This sucks,” his wife said. The nightmares have lessened.

That’s precisely the goal of therapy, said Gray, the VA therapist. It challenges him to examine his beliefs and trigger points to see why they might be illogical or irrational.

“There’s a good reason why those are triggers for him,” Gray said of McAnally’s severe reactions to unknown objects on the road. “That’s how people die in Iraq.”

But over time, through therapy, she said, “those triggers dramatically reduce, and in some cases, they do go away.”

McAnally said the writing helps him remember what happened, but not carry the burden every day.

“I think a lot of the intrusive thoughts about what happened are related to my fear of forgetting, and if it’s written down, I can kind of let it go,” he said. “Those memories are all I have from war. … And I want to remember what happened and everything I did. It is a huge part of me.”

At the same time, he wants to be free to live his life – to snowboard in the winter and water-ski in the summer, to start a family, to become a social worker and help other veterans.

Normal stuff.

Picking up one of his stories, he said, “There was a time when I couldn’t read that aloud. I can read it aloud now. To be able to talk about it, to live with it and be OK with it, I’m moving toward there.”