Fire crews drew heavily from immigrants, laborers

Forest Service employed 10,000

George Earle was looking for work.

The 30-year-old English immigrant had recently arrived in Spokane by foot from Alberta, following the railroad tracks into a new country. An ex-solider and ranch hand, he was a veteran of both South Africa’s Boer War and the grinding physical labor of daily farm life.

In Spokane, Earle signed up for a temporary firefighting job with the U.S. Forest Service. The pay was 25 cents an hour, meals and bedroll included.

“He basically walked into the employment of the fires,” said his granddaughter, Barb Montgomery. “That’s where his life in this country began.”

Earle’s story is typical of the men recruited to fight the 1910 fires. With forests in flames from the Clearwater to Glacier National Park, the Forest Service had 10,000 men on the fire lines in Idaho, Washington and Montana. Their job: Keep the blazes from devouring valuable stands of timber, and protect nearby towns. Not surprisingly, much of the hot, dirty work fell to immigrants. The fire crews contained Croats, Latvians, Italians, Greeks, Germans, Scandinavians and Japanese. Some spoke no English. Others had no woodland experience. They joined other day laborers – a flotsam of itinerant men wandering the West.

The men were plucked from hiring halls, lumber camps, mines, saloons, railroad depots and even jails.

“You might have been passing through on a train, and grabbed and put on a fire crew,” said Jason Kirchner, a spokesman for the Idaho Panhandle National Forests.

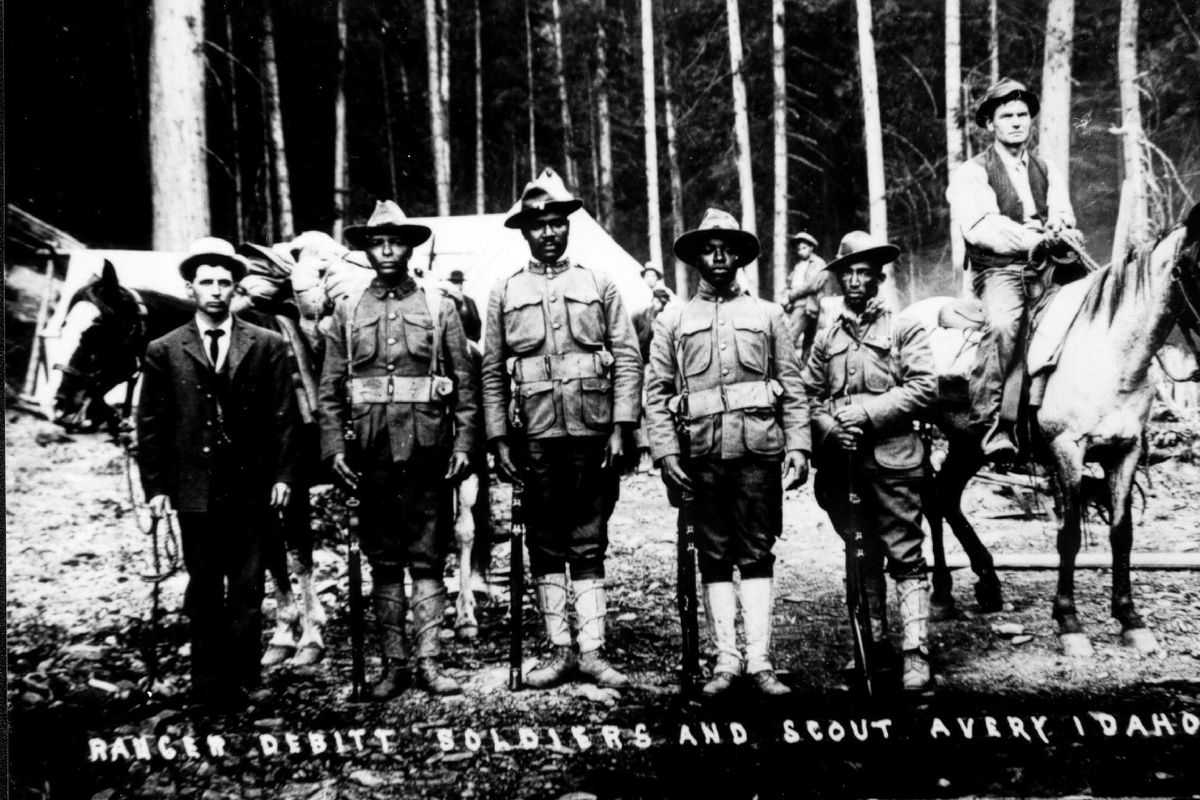

As the wildfires grew in number and intensity, one ranger arranged to have 60 prisoners released from the Missoula jail. Elers Koch, supervisor of the Lolo National Forest, hired hobos from trains, sending the sober ones out to fire camp the next morning. Later, President William Howard Taft sent soldiers to assist the firefighting efforts.

Few of the men “had a cent in their pockets…” Koch said of his hires, “nor did most of them have a permanent address to which a check could be sent.”

Forest Service rangers used “guile, threats and enticements,” to staff their crews, wrote Stephen Pyne, author of “The Year of the Fires.”

“They gathered the willing, the able, the enfeebled, the derelict, those fleeing murky pasts and those fleeing to dim futures…whatever the labor markets in Butte, Spokane and Missoula could flush out,” Pyne said. John J. Stanton, a 24-year-old Latvian immigrant, hired on for the wages. The average American worker earned about $13 for a 60-hour work week in 1910. At 25 cents per hour, a firefighter could clear $15 a week.

“I was looking for a job about the time of the fires broke out and they were looking for firefighters, so I joined the cause,” Stanton told The Spokesman-Review during a 1969 interview. “It was pretty good money, but it was a risky job.”

Special trains took Stanton and other hires to Coeur d’Alene, where the firefighters were loaded onto steamboats and taken across the lake and up the St. Joe River. Stanton was assigned to a fire crew near Avery.

Each crew had roughly 20 men. First, they had to find the fires, often hiking several days to reach them. Then, working with hand tools, they could build about a mile of fire line per day.

Desertion was common. One crew walked off the job over rations, complaining that each firefighter got only a small can of beans after a day of exhausting labor. But firefighters also quit for petty reasons, soured by the backbreaking physical work and isolation.

Exasperated rangers wrote about the difficulty of keeping the men motivated. Managing the crews was more difficult than fighting the fires, groused Koch.

“Time and again a whole crew would walk out at a critical time for some trivial reason,” he said. “If we were lucky, there would be enough good lumberjacks in a crew to fill the axe and saw gangs, and the punks and stew bums would be given a shovel or mattock to get the best they could out of it.”

Earle earned a much better report from his supervisor. He ended up with Ranger William W. Morris on Graham Creek, a tributary of the North Fork of the Coeur d’Alene River, and stayed until the September rains started.

“Around the campfire at night, I had a chance to size up my crew,” Morris later wrote. “One was a young Englishman who fought in the Boer War. He could tell many exciting stories of his experiences, and also was quite a poet and singer. Often, he held the attention of the whole camp as he recited bits of poetry of his own composition, or sang some old English airs.”

Morris also praised the work ethic of two Montenegrin firefighters and a lumberjack named “Patsy” who “dashed into the fire with buckets of water or shovels of earth, as cool as a cucumber…”

If Earle was typical of the men hired to fight the fires, Morris was representative of the men in charge. He was an idealistic 29-year-old, a recent forestry graduate from the University of Michigan. Like other devotees of Gifford Pinchot, the first chief of the Forest Service, Morris joined the cause of conservation when he was hired by the agency. He sent rapt letters to his family in Chicago, describing his life as a ranger in the Coeur d’Alene Mountains.

Many of the other rangers were also young, relatively untested leaders.

During the blowup on Aug. 20, Morris’ crew fled during the night from their ridge-top camp. They made it safely to an opening several miles away.

Stanton’s crew wasn’t as fortunate. He described escaping to Avery with another firefighter when the fire blew up. At the cook’s urging, others remained in camp to eat dinner, Stanton said. None survived.

Later, Stanton was sent with soldiers from Fort George Wright to retrieve the bodies. Nearly 60 years later, the scene still made an impression on him. “Many of the men were in the water of a creek, face down,” he recalled. “Their faces weren’t burnt, but their backs were. The water in the creek had gotten so hot that all the fish died.”

Stanton was probably describing the crew at Storm Creek, a tributary of the St. Joe River. Led by the 59-year-old camp cook, Pat Grogan, a tough-talking Irishman, 28 men refused orders to evacuate to Avery.

Accounts of Grogan’s persuasive speech vary. In one version, he told the men that standing their ground offered the best chance of survival. In another account, Grogan questioned the fire’s severity, saying “I don’t feel like no six-mile hike this time of day.”

Storm Creek proved the deadliest spot during the 1910 Fire. All 28 men who stayed died. The rest of the crew reached Avery safely.

In the end, the fires took the heaviest toll on the raw recruits pulled in to work the fire lines. Of the 78 firefighters who died that August, not a single one was a ranger or a soldier, Pyne noted. Many of the bodies would never be identified. The men were simply names, jotted down in the timekeeper’s record book.

Stanton spent two more summers fighting fires. In 1912, his mother sent him a ticket home to Pittsburgh.

Earle worked for the Forest Service for 31 years. After the fire, he was a timber cruiser, marking burnt logs for harvest. He became a U.S. citizen and retired from the Kootenai National Forest as the timber division’s senior ranger.

His granddaughter, Montgomery, remembers Earle as a tall, thin man. He smoked a pipe, and entertained his grandchildren with stories of South Africa.

Montgomery works as a geographic information systems analyst for the Idaho Panhandle National Forest in St. Maries. She’s also a certified wildland firefighter, as are her son and her husband.

“It’s a proud heritage for us,” she said. “I think it’s in our blood – maybe beginning in 1910.”

Sources for this story include: “The Great Fires of 1910,” an article by William Morris; “The Year of the Fires,” by Stephen Pyne; “The Big Burn,” by Timothy Egan; “Northwest Disaster,” by Ruby Holt; The Spokesman-Review archives.