Stockton joins hardwood greats

Gratitude-filled talk pays tribute to family, Spokane

SPRINGFIELD, Mass. – All John Stockton ever asked was a chance to prove himself against the best – whether that was his older brother Steve in the family driveway on North Superior or Michael Jordan in the NBA Finals.

Now the proof is in: his induction Friday into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

The Hall’s 50th induction class was possibly its most distinguished, headlined by the incomparable Jordan and including fellow NBA and Olympic champion David Robinson, Stockton’s longtime Utah Jazz coach Jerry Sloan, and C. Vivian Stringer, the only college coach in history to take teams from three schools into the NCAA Final Four.

“So what am I doing here?” Stockton cracked.

Just accepting his due as professional basketball’s most prolific passer and most durable little man, as well as one of the game’s fiercest competitors – qualities validated by election to the Hall in his first year of eligibility.

He paid particular tribute to his family and his Spokane roots in an 11-minute speech mixed with tears and the humor he often concealed from fans and the media.

“Out there is a large group of people,” he said, “who traveled over 1,000 miles – some from Hawaii, some from Alaska – just to support me.

“I almost started laughing there because I think they actually came to see Michael.”

Jordan, whose Chicago Bulls beat Stockton’s Jazz in the 1997 NBA Finals and again in 1998 with a game-winning basket, laughed along with the rest of the full house in Springfield’s Symphony Hall.

“He makes one big shot and everybody thinks he’s kind of cool,” Stockton teased.

Spokane thought it was kind of cool to send one of its own to the National Basketball Association for the first time in 1984, when the Jazz made Stockton their first-round draft pick upon his graduation from Gonzaga University – then, unlike today, flying well under the college basketball radar. Stockton could hardly believe it himself, even when a 19-year pro career followed.

“I played 30 years competitively,” he said. “Three at St. Aloysius, four at Gonzaga Prep and four at Gonzaga University. And in all those years, not once – ever – was I the best player on the team. I had a shot at it one year (at GU) because two of our best players got hurt.

“I wasn’t even the best player in my own house. My brother Steve boasts a record of about 1,000-1 in bloody driveway battles. That one victory, though, ended all the games. That’s my one claim to fame with Steve.”

Just like the great point guard he was, Stockton spread recognition around to boyhood friends, former teammates and coaches and his large and devoted family, including sisters Stacey and Leanne and his six children – Houston, Michael, David, Lindsey, Laura and Samuel.

Of his father, Jack, whose Hamilton Street tavern became the obvious headquarters for a large local fan following, Stockton called him “my idol – always have been, always will be.” And tears overcame him when he remembered his mother, Clemy, who died three years ago after a battle with cancer.

“She had tremendous strength and grace,” he said, “and she deserved to be here.”

But the smile returned when he acknowledged Nada, his wife of 23 years.

“Dad used to say that girls will ruin your game,” he said. “I’m pretty sure he’s right, but I couldn’t hold out forever. Actually, my youngest son pointed out that I got better once I had his mom to show off to.”

While Jordan took particular delight in his acceptance speech in tweaking any number of doubters or others whose slights fueled his competitive resolve, the 47-year-old Stockton seemed to enjoy chronicling his humble basketball beginnings and taking shots at himself.

He noted that he’s “proud to be a Zag” and how “Gonzaga has come a long ways – they have towels and actually have a shower in the locker room now.

“Jerry always used to say you have to travel the old yellow school bus once in a while to appreciate things. Well, we appreciated a lot at Gonzaga because we rode in broken vans and a broken blue military bus. If we could get to a game, we thought we had a chance to win.”

He remembered the Jazz fan reaction at his being drafted as a mixture of “Who?” and “Boo,” and agreed that then-general manager Frank Layden had gone out on a limb with the pick because “I had to be the only player … that was still living at home with his parents at the time of the draft.”

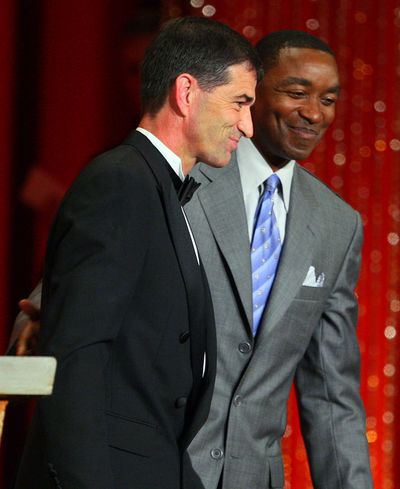

And he acknowledged his teammate of 18 years, Karl Malone, who couldn’t attend because of a family illness but is likely to be elected to the Hall in the next round of voting.

“He was our best player for 18 seasons and drew a lot of attention,” Stockton said. “I wish he was here tonight drawing a little attention – it’s mighty lonely up here. But I’m going to save this tuxedo and press it up for next year.”

Not surprisingly, there was no mention of assists or steals – Stockton holds the NBA career records for both – or the 10 All-Star Game appearances he made, or the two Olympic gold medals he won. He sat with his family through the highlight and tribute video that preceded his speech with little emotion. For Stockton, the night was about gratitude.

“To all the people who touched my life, helped me along and brought out the best in me by whatever means, I’m overwhelmed and, yes, humbled,” he said. “I can’t begin to adequately thank even a few. I feel honored to stand up here in front of you and represent you on this stage tonight.

“To everyone back home in Spokane or back home in Salt Lake City – or maybe wandering around Springfield looking for a ticket, or anywhere else they might be – thank you for sharing this honor with me tonight.”