A family man now

‘Kamiah Kid’ still a proud Vandal

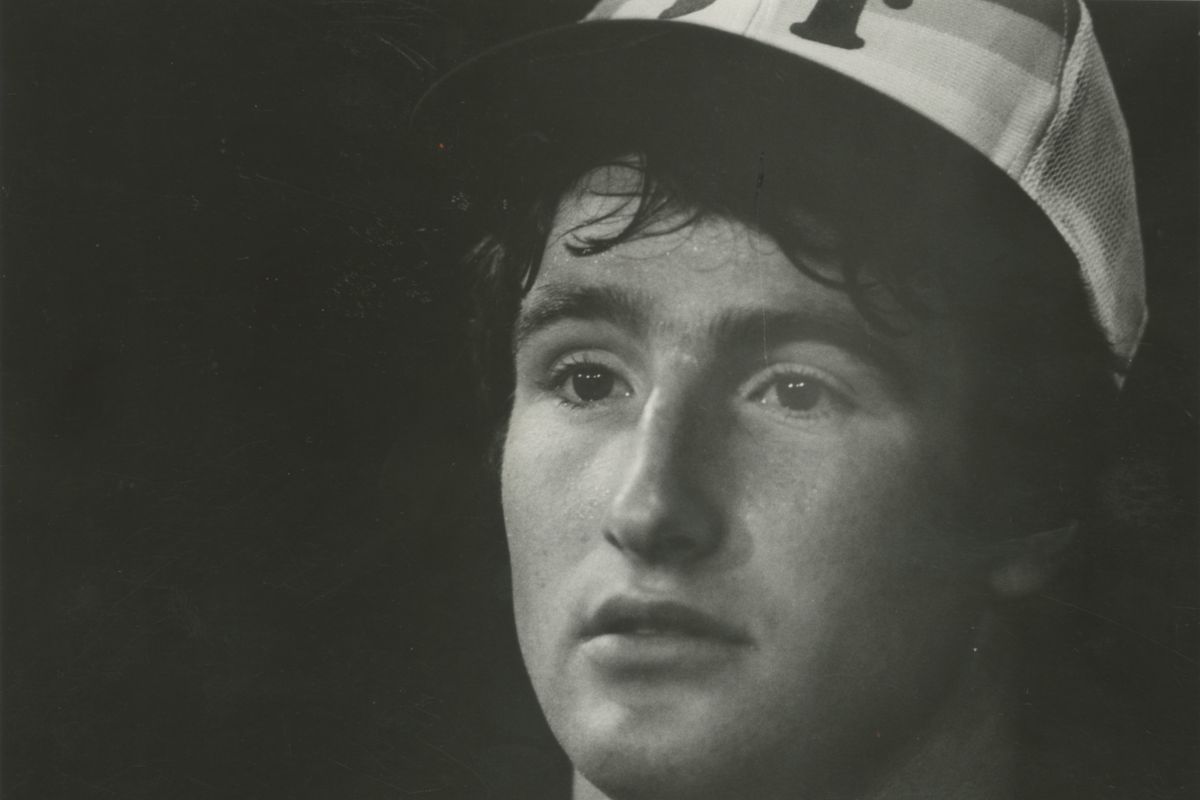

Hobart had pro stops in the USFL and the CFL.Spokesman-Review archives (Spokesman-Review archives / The Spokesman-Review)

MOSCOW, Idaho – To this day, nearly 30 years later, the pointed words still rattle in Ken Hobart’s mind.

It was the end of the 1981 season, and Hobart went to the University of Idaho football banquet unsure if he would remain a Vandal or transfer to the University of Houston. Idaho was about to ditch the veer offense, a system the Cougars ran and one that seemed to mesh perfectly with Hobart’s quarterbacking skills.

He had, in fact, rushed for almost as many yards (829) in 1980 as he had gained through the air (1,083). But with Jerry Davitch out as head coach, the Vandals were set to embark on a pass-happy Dennis Erickson era.

Could Hobart handle the change? Bill Belknap, UI’s athletic director at the time, apparently was skeptical.

“Well, what are you going to do next year?” Belknap asked Hobart at the banquet. “You’re going to have to throw the ball.”

The short conversation, as Hobart recalls it, was all the small-town walk-on needed to stay. Two years later, he had shut up his doubters by becoming one of the most decorated – and complete – quarterbacks in Idaho history, setting the stage for a seven-year pro career.

“It ticked me off,” he said of Belknap’s comment. “I used that as motivation. I remember that night telling my mom, who was at the banquet, ‘Mom, I had talked to you about maybe transferring to Houston.’ I said, ‘I’m not transferring. I’m going to stay at Idaho. I know I can throw the football.’ ”

Hobart, 48, reflected last week about that moment, and many others, in his scattershot athletic career from his office in Lewiston, where he sells billboard advertising and helps his wife, Val, in her real estate business.

Hobart has stuck close to his north-central Idaho roots since ending his Canadian Football League career in 1990. He still travels 35 miles north to Moscow on most game days to watch the Vandals, and he stays in close contact with a handful of old teammates.

Yet these days, the man who used to be known as the “Kamiah Kid” – a nickname that refers to his hometown of Kamiah, Idaho, about 65 miles southeast of Lewiston – is fully consumed by his three children’s athletic pursuits.

His eldest son, Zane, will play baseball this spring for Walla Walla Community College. His two junior high-aged daughters, Klaree and TaLaynia, are preoccupied with volleyball.

A devotion to family has kept Hobart from pursuing any sort of coaching gig, despite having many chances to enter that world.

“Just look at Dennis,” Hobart said of Erickson. “He was in Moscow, then he bounced down to Wyoming, then he bounced to (Washington State), then he was at Miami. You just uproot your family and your kids.”

Hobart had become all too familiar with life on the road during his time in the USFL and Canada. He prospered during most of his post-UI playing days, but he was always left feeling his true opportunity – in the NFL or otherwise – never materialized.

Hobart was drafted by the New York Jets in the 1984 supplemental draft, but he opted for immediate playing time with Jacksonville’s USFL franchise. That was followed by stops in Hamilton and Ottawa in the CFL.

Tired of the frenetic lifestyle and physical beating, Hobart stepped away from football at the age of 29.

“Collegiately, I was at the right place at the right time and was given the opportunity and did well with it,” Hobart said. “Professionally speaking, I was just never in the right place at the right time. I knew I could have played, but I just never could get the right break, it seemed.”

Hobart openly wonders what might have been had he chosen any number of different paths. After starring at Kamiah High, the late-blooming athlete enrolled at Lewis-Clark State College in Lewiston and was poised to pitch for illustrious coach Ed Cheff’s baseball program.

He had an elite pitching arm, but he grew disenchanted with the idea of playing behind a group of seniors and transferred to Idaho. His roommate at LCSC, Tom Edens, went on to pitch for the Minnesota Twins and five other big league teams.

“I really think to this day, if I had stayed at LCSC and played baseball, I think I would have an opportunity to play Major League Baseball,” he said. “That’s how confident I was in my abilities.”

Hobart’s time at Idaho helped him put aside his baseball ambitions. In his four years on the Palouse, he set 12 Division I-AA records and became only the second player in NCAA history to accumulate more than 10,000 yards. (If that weren’t enough, he was a standout decathlete.)

The bulk of Hobart’s eye-opening football numbers came in two years in Erickson’s wide-open system. Midway through the coach’s first year in 1982, Hobart went from a solid running QB to one who knew every facet of Erickson’s playbook and was thriving with his arm.

It helped to have his new coach in his corner.

“He pulled me aside (after he was hired),” Hobart recalled. “He said, ‘Hey, I’ve been watching a lot of tape and film on you. You know what, I was told you can’t throw the ball. … They’re crazy. You can throw the football. And you’re going to be throwing the football.’ ”

Erickson was right – unlike so many others.