Radon remains a silent danger

Education has receded, but it continues to be a public health concern

As Debbie Greenman lay on her stomach, the doctor pushed a needle through her back to extract a bit of lung tissue.

She was nervous yet confident about the biopsy.

“I thought, ‘No way. This can’t be happening to me. I have never smoked. My parents never smoked. I’m a runner.’ So what happened was just completely unexpected,” said the third-grade teacher at Evergreen Elementary in north Spokane.

Her story highlights an important local public health issue that went largely quiet 10 years ago when funding disappeared and priorities changed.

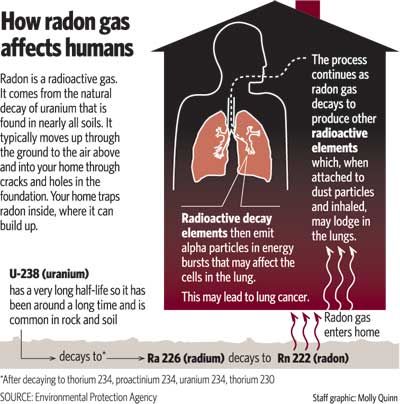

The Spokane region – including Kootenai County – is a hot spot for radon, the colorless, odorless, naturally occurring gas ranked as the second-leading cause of lung cancer, behind smoking, in the United States.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates 21,000 people die of radon-related lung cancer each year.

State and local health officials believe 60 percent of the homes in Spokane County have elevated levels of radon based on the testing of thousands of homes over the years. Today they worry such testing has grown lax and that the threat posed by radon has dropped from the public health debate.

“I’m not panic prone, but after looking at the models and science regarding radon in the home, what we have here is clearly a public health concern,” said Mike Brennan, a radiation health physicist with the Washington State Department of Health. “Let’s face it: To have radiation decay in your lungs is not good for you. As I tell people, if I were moving to Spokane, I would absolutely make any real estate transaction contingent upon having a satisfactory radon test.”

A radon trap

Greenman calls herself lucky. Physicians caught her cancer early, at stage 1, while running routine tests in preparation for an unrelated surgery.

It didn’t take them long to find ominous spots on the lower lobe of her left lung in a chest X-ray.

So five days after Christmas, surgeons cut it out, reducing her lung capacity by 20 percent. She now uses an incentive spirometer that measures how well the lungs fill with each inhalation.

Though she acknowledges that she will never know what caused her cancer, radon gas is a suspect.

It didn’t take her long to reach a best-guess conclusion. When doctors told her about the cancer, she did what anyone stricken with a surprise illness would do: “I began to research on the Internet.”

She learned from the American Lung Association and the American Cancer Society Web sites that radon causes lung cancer. She dug deeper, found corroborating scientific materials published by federal health and environmental experts. So she drove to the local hardware store, bought an $8 test kit, set it up in a few minutes and waited.

She sent the kit to the test lab. On the same day surgeons were cutting away part of her lung, lab workers in Florida were analyzing her radon kits.

When she was well enough to go home, she opened her e-mail and read the results.

Greenman would have gasped, but her lungs were too weak. The radon levels from two basement bedrooms showed 214.5 and 193.4 picocuries per liter.

“I thought maybe they had the decimal point wrong,” she said. The EPA considers 4 picocuries per liter dangerous enough to take action. A picocurie is a measurement of radioactivity units.

With the levels at her house “off the chart,” Greenman promptly moved with her husband, Jerry, into the Deer Park home of her parents – Clarence, a former nuclear engineer at Hanford, and Wanda Kassens.

David Gerard, of Advanced Radon Technologies Inc., arrived at the Greenman home skeptical of the numbers. He has helped engineer and install radon mitigation systems in the region for years.

Rarely has he seen a reading that high.

So he set up more sophisticated equipment at the home on Deer Lake north of Spokane. It was built in 1998 with a system that was supposed to vent the radon out of the house.

His tests came back showing picocurie levels of 250.

He began running more tests and determined that the Greenman home was built wrong when it comes to radon. It was a trap.

This past week he finished installing a system of pipes that will collect the radon and blow it out of the home using a fan.

Greenman has said she won’t move back in until plenty of tests are run that prove the home is safe.

Drop in awareness

The problems of radon at the local level hit hard in the 1980s.

It was a time when more people were responding to weatherization initiatives and sealing their homes for energy efficiency. At the same time, radon testing was becoming widespread and tests began showing that Spokane had problems.

The city hosted a national radon conference in 1986, and the Spokane Regional Health District launched education programs, consulted with residents, and published regular advertisements in local media about radon testing and mitigation measures.

“I like to think that we were making a difference,” said Mike LaScuola, an environmental health specialist at the health district who used to run the radon program.

The district used the several thousand test kits it sold at cost to plot on a map those areas with high radon levels. It used this work to identify neighborhoods, schools and commercial properties that may be especially prone to radon problems.

The information was strong enough to change building codes. All homes built in Spokane County since the early 1990s must include radon mitigation systems.

The innovative programs and results earned the radon program awards from the EPA and the National Association of Counties.

Most builders embraced the radon measures, LaScuola said. The work is relatively easy, with the right fill material and pipes placed before the foundation is even poured.

The systems are initially passive, meaning that the gases are allowed to collect in the perforated pipes under the foundation and then travel up and out of a vent. When the houses are finished and ready for occupancy, radon tests are conducted to see if the system needs to be activated. If so, a small fan inside the vent pipe is turned on to help draw the radon up and out of the home. A radon mitigation system usually costs less than $1,000 to install in a new home, depending on the home’s design and size.

Installing radon mitigation systems in older homes can cost more because of extra placement work.

The work of the local health district became a casualty of Initiative 695, which slashed many public health programs, LaScuola said.

“Sure radon is just a facet of the hazards of living,” he said. “But, with the radon program being cut, that awareness began to fade away.”

Today the local health district refers people with radon inquiries to materials posted by the EPA.

“When I think about what we were able to do and improve people’s lives like through radon education and testing, we knew we were helping,” LaScuola said.

Local phenomenon

The Spokane area has an interesting geology that gives it a very high prevalence of radon gas, according to information from the Washington State Department of Natural Resources.

“In your corner of the state, there’s more uranium and radium in the ground than in other places,” Brennan said. “There were, after all, three uranium mines there.”

Despite the problems, there is no evidence of elevated levels of lung cancer in the Spokane region due to radon.

Reasons vary, Brennan said. Radon in homes wasn’t measured until the 1980s. Historically, Spokane has had higher smoking rates compared with the state as a whole. And since it may take many years for radon to affect the lungs, many people move and don’t make a connection.

And there’s this: Not everyone exposed to high levels of radon develops lung cancer, just as some lifelong smokers never get lung cancer.

“Here’s what we do know: Radiation can cause cancer,” Brennan said. “We know people exposed to high concentrations, in job fields such as mining, have a higher incidence of lung cancer than can be explained. So something was happening that has been causing lung problems for miners.”

Brennan said that what worries him about Spokane homes is that so many of the radon readings are so high.

“That’s why we are encouraging people to test their homes,” Brennan said.