Magnuson had vision for region

Silver Valley mining magnate, businessman dies at age 85

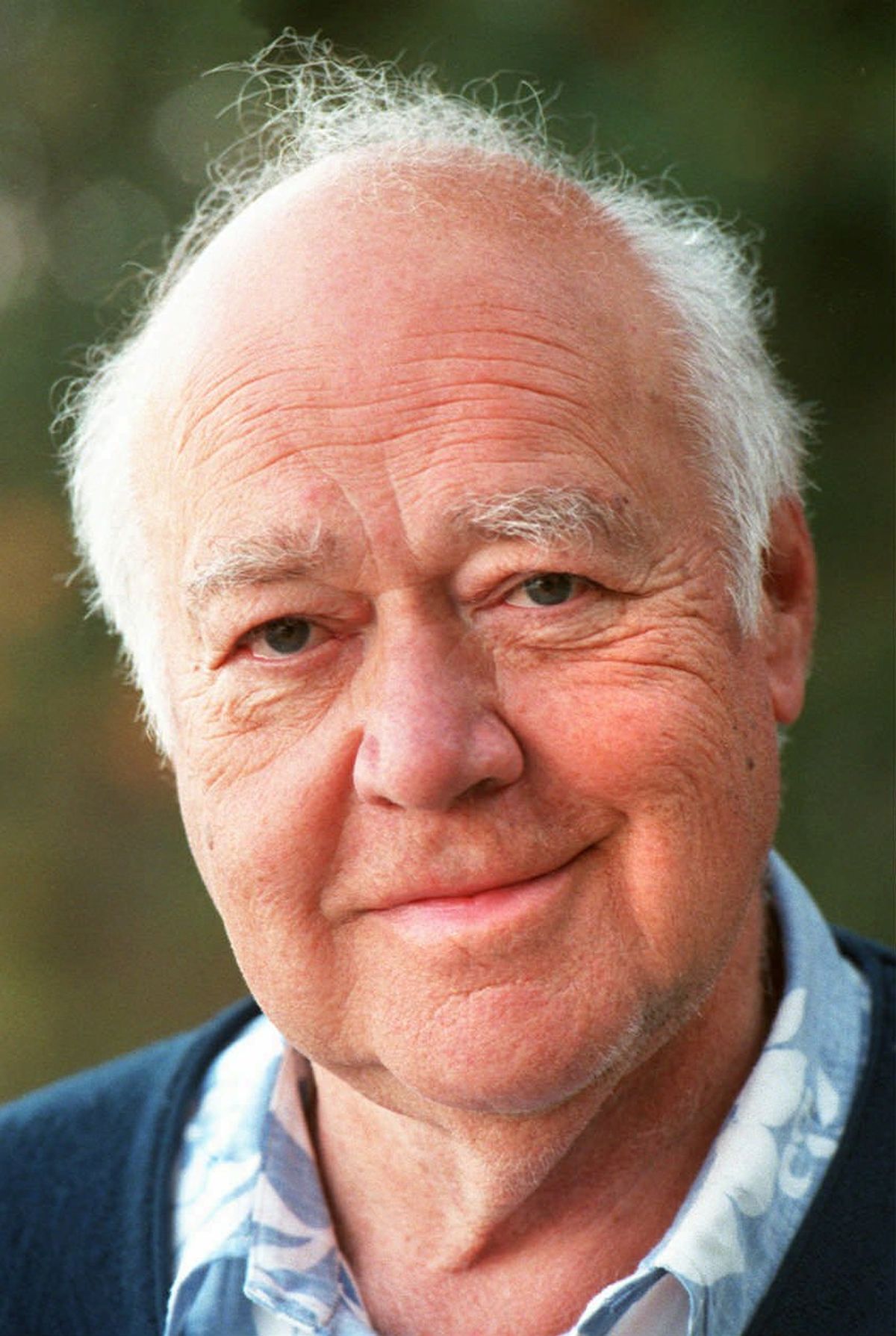

Magnuson (The Spokesman-Review)

People called Harry F. Magnuson “Mr. Wallace,” but his reach stretched far beyond his hometown.

He saved historic buildings from wrecking balls and helped rescue Gonzaga University from financial collapse. Magnuson believed that tourism and recreation would revive his beloved Silver Valley, and he lived long enough to see his vision become reality.

Magnuson, 85, died Saturday at Sacred Heart Medical Center in Spokane. His son, John Magnuson, said his father was being treated for pneumonia when he died of a heart attack.

“Everybody has a Harry Magnuson story,” said Ron Garitone, mayor of Wallace. “The man loved the little town. He grew up in it. He still has a house here. He’s what we’d call a ‘good old Wallace boy,’ but his (influence) goes way beyond our little community.”

Magnuson’s grandparents settled in the Silver Valley and worked its mines, ran its boarding houses and fed miners in its restaurants. Magnuson was born March 14, 1923, one of three sons of a father who owned a meat market and acted as the town’s unofficial historian. The elder Magnuson instilled in his boys a “strong sense of history and a strong sense of family ties,” as Magnuson’s brother, Richard, once said in an interview.

Magnuson was recruited into the Hecla Mining Co., right after graduating from Wallace High School. Magnuson served in the Navy during World War II and eventually finished a master’s degree in business administration from Harvard Business School. He returned to Hecla but left shortly after and “with money from his mother, his lifelong confidant and business adviser, he set himself up as a public accountant,” writes John Fahey in “Hecla: A Century of Western Mining.”

But while developing his accounting firm, H.F. Magnuson Co., he kept his hand solidly in the mining business. He was on the boards of Hecla, Golconda Mining and Bunker Hill and was president of the Silver Dollar Mining Co., among many other mining ventures and investments. He was always referred to as a “mining magnate” in newspaper stories.

The firm grew to include real estate, banks, hotels and shopping malls throughout the Inland Northwest, from the Moscow Inn in Moscow, Idaho, to University City in the Spokane Valley.

In a 1990 interview with writer Cynthia Taggart, he said: “I started from scratch and have been scratching ever since.”

He was able to use his financial talents to help Gonzaga as it struggled financially in the late 1960s. Magnuson joined its board of trustees.

“We nearly suffered a financial collapse, and Harry guaranteed our loans with his assets,” said Father Robert Spitzer, GU president. “He went out on the proverbial limb and kept GU alive. He loved us. We loved him right back.”

Magnuson also looked toward the future and planned for it, long before others even saw it coming.

“Mining was good to him,” said friend Bob Templin, a Post Falls resort and restaurant entrepreneur. “But he had the vision to see the downturn in mining coming. He would have liked to see mining survive and (remain) energetic in the communities in the Silver Valley. But he could see where it was headed. He remembered the early days of tourism, and he knew it needed to be revitalized.”

Magnuson had his share of controversies, too. In the late 1970s, he fired reporters on the North Idaho newspaper he owned; they accused him of suppressing views that differed with his own. He ran into trouble with the Securities and Exchange Commission. And he faced several lawsuits over mining issues, as well as property and building projects.

But still, he was invited to every meeting of importance in North Idaho, Templin said, because “he had great vision and determination. If he felt something needed to be done, he got it done.”

His passion always remained with historic preservation. He helped start the Wallace Mining Museum, preserved Wallace’s Northern Pacific Depot and worked on the restoration of the historic Cataldo Mission, where his Italian grandfather spent the winter in 1893 after the mines shut down, according to Taggart’s story.

Magnuson also battled – for 17 years – an I-90 construction plan that would have wiped out one third of Wallace. When government officials told him the plan couldn’t be changed, he said, according to Garitone: “Oh yes, it can be changed. You don’t have to take out all our historic buildings.”

The result? The elevated freeway that runs through Wallace today.

Former Idaho Gov. Cecil Andrus, who knew Magnuson for 50 years, said: “He made absolutely sure that city did not disappear.”

Magnuson was a private man who rarely talked in depth about his life or accomplishments. He kept a lot of his generosity a private matter, too. “Nobody really knows, except maybe his wife Colleen, about his generosity,” Templin said. “It reached far and wide, not just in Wallace.”

He is survived by his wife, three sons, two daughters, nine grandchildren and two brothers. Services are tentatively planned for Thursday in Wallace at St. Alphonsus Catholic Church.