Sentence angers victim’s mother

Gang loyalties, unhelpful witnesses hindered homicide case, authorities say

Rae Walton, whose son was shot to death by gang members outside a late-night beer party in 2007, is having trouble understanding the judicial system in Spokane.

How can a young man who suffered two gunshot wounds as he sat alongside her slain son be ordered to serve more time in prison for lying to authorities than the man who pleaded guilty in the death, who could have received 23 years behind bars but instead spent just 11 months there?

“That’s a joke,” said Walton, who disputes police claims that her son was also a gang member and an informant.

“We get no justice.”

Authorities acknowledge the shooter received an exceptionally light sentence.

But, they say, the deal ended a case marred by uncooperative witnesses with criminal backgrounds, gang loyalties, a disdain for police and fears of retaliation against snitches.

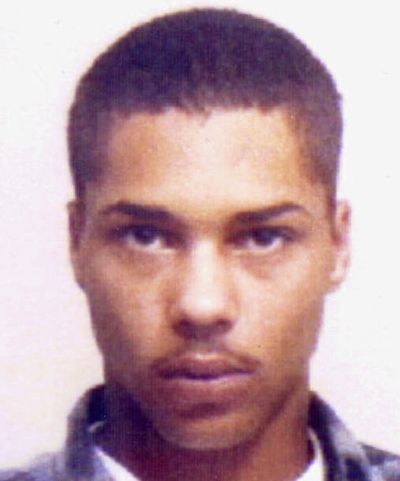

Adama R. Walton, 28, died in September 2007 after being shot twice while behind the wheel of his girlfriend’s gold Chevrolet Avalanche, which flipped as he sped away on North Perry Street with the other victim, Kenneth R. Budik.

“Kenny Budik is probably the most uncooperative witness we had in the entire case, and he’s a victim,” said Spokane police Detective Kip Hollenbeck. “That’s a perfect example of how this case went.”

Now Budik, 21, is the only one in prison. Shot in the shoulder and knee, he was found guilty of lying about what he knew about the crime.

The suspected assailants, Freddie J. Miller, 28, and Titus T. Davis, 31, originally were charged with first-degree murder. In November, Miller pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of rendering criminal assistance and was released after serving about 20 days in jail on top of time he’d already served, for a total of six months in Spokane County Jail.

Davis went to trial last fall, but a jury couldn’t reach a verdict. Now he’s out of a jail thanks to a plea deal approved by Superior Court Judge Ellen Kalama Clark that reduced the charge to first-degree manslaughter and spared him probation. Davis, whose prior convictions included burglary, reckless endangerment and two second-degree assault charges, was released Jan. 22, the day of his sentencing, after getting credit for time served.

The manslaughter charge carries a standard sentence of 17 to 23 years in prison and two to four years of probation. Davis’ light sentence was part of his plea deal.

“Those guys are out walking the street again,” Hollenbeck said. “I hate to say it … but there’s nothing we can do.”

Davis’ defense maintained his innocence, and six of 12 jurors refused to convict him.

Prosecutors agreed to the lenient sentence at a time when authorities are expressing greater concern over gang-related violence in Spokane. Deputy Prosecutor Mark Cipolla, who handled the case, did not return phone calls left last week and Monday seeking comment. Defense attorney Kari Reardon declined to comment.

Police tactics and witness credibility were central to the defense, court filings show.

“When he could not get witnesses to cooperate with his theory, Detective Hollenbeck sought criminal charges for rendering criminal assistance,” Reardon wrote in a 49-page court trial memorandum filed Oct. 20 in Spokane Superior Court.

Court documents show that witnesses, some of whom said they were drunk at the time of the shooting, told police conflicting stories about the incident. Davis, for example, wasn’t initially fingered as the gunman.

Other court papers show that Budik told police informants that another man who was with Davis fired shots. His first-degree rendering criminal assistance charge came after he told police later that he knew nothing about the homicide.

Budik “told investigators that these people knew where his family lived and he had to think about protecting himself and his family,” a police report says.

Eight witnesses in Davis’ trial were transported from the county jail to testify. Plea deals in separate criminal cases in exchange for testimony are common in gang-related cases, Hollenbeck said.

“If this murder was witnessed by the average citizen,” Hollenbeck said, “we wouldn’t have to go through all these hoops to get them to testify.”

In the end, the prosecution only had witnesses pointing to Davis as the shooter. They had no forensic evidence, such as a murder weapon or fingerprints, court papers show.

Walton’s slaying came after spending a night drinking at a North Division Street bar and a party that lasted into the early morning, according to court documents. But by the time police responded to reports of gunshots about 3 a.m., just minutes after the call, the house was nearly deserted, Hollenbeck said.

“That kind of tells you the type of people you’re dealing with,” he said.

In court documents Reardon agreed with police that Walton, who had recently been released from prison on drug charges, was a gang member and a police informant. But she disputed police claims that Davis belonged to a gang, saying evidence could only prove that he’d been seen with gang members.

In her trial memorandum, Reardon compared that association method to the Hollywood blacklisting methods employed during the Joseph McCarthy anti-communism era. She also hammered investigators for focusing only on Miller, Davis and a third man, Jawaun Nave, who was never charged.

“They did not consider any of the numerous other potential suspects that Mr. Walton had harmed in the past, nor did they consider any of the numerous people on whom Mr. Walton had acted as a confidential informant,” Reardon wrote in her trial memo.

Walton’s mother, Rae, said she is devastated by the sentences handed down in her youngest son’s death.

“It’s just not fair,” she said.

Hollenbeck said the case came down to the witnesses, whom investigators have no control over.

“I wish the outcome was different,” Hollenbeck said. “But in the end, I think we got the best we could out of it.”