A father lost, a father found

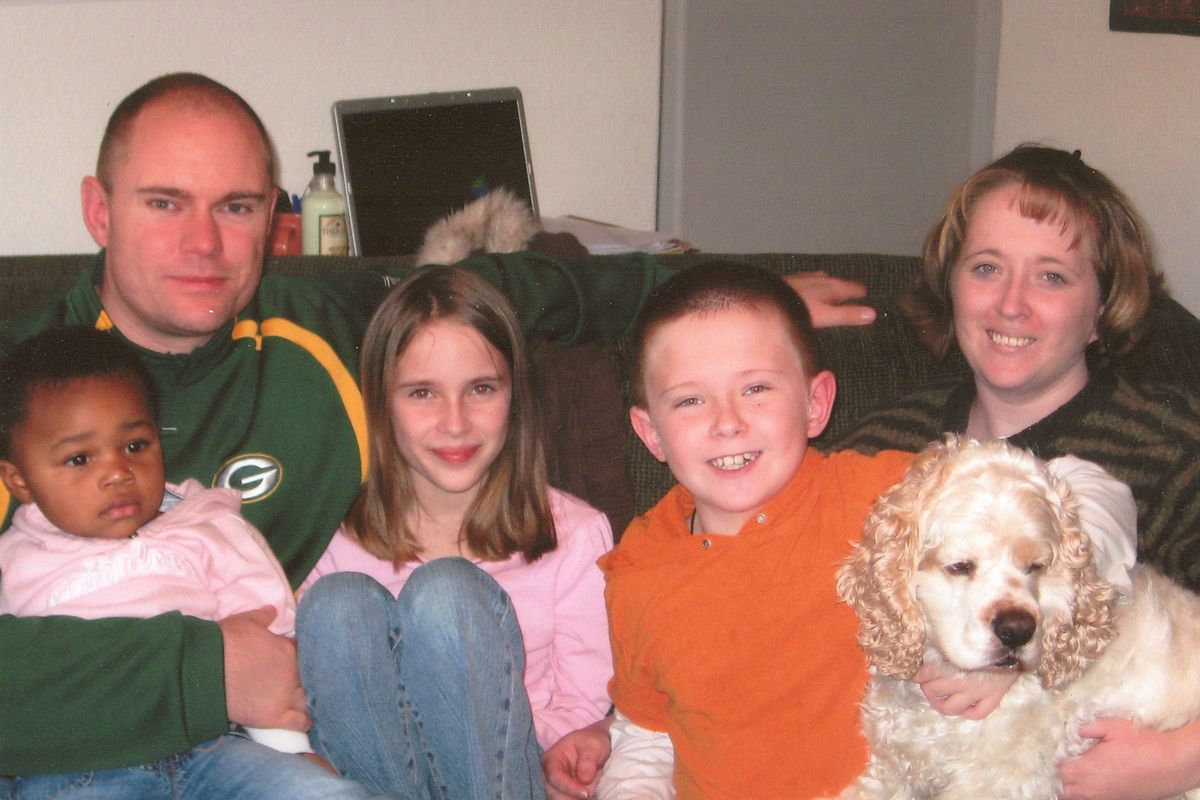

Zak Gilbert, the biological son of Keith Roberts, is pictured with his family, from left: daughter Caitlynn, 3, Ashlynn, 11, Braden, 10, and wife Jennifer. Courtesy of Zak Gilbert (Courtesy of Zak Gilbert / The Spokesman-Review)

A “John Doe” was found dead in a van in downtown Spokane on June 14, 1983. In 2006, thanks to a “cold case” investigation, Spokane County medical examiner’s office staffers discovered his identity: Michael Keith Roberts.

County staffers, along with others in the community, paid for a headstone and held a memorial service for Roberts. The Spokesman-Review did a series of columns in summer 2006 on the “Michael Mystery.”

End of story? No.

Recently, Zak Gilbert, 33, of Fort Collins, Colo., contacted the newspaper. Roberts was Gilbert’s biological father.

Gilbert didn’t know how his dad had died until a relative alerted him – just this June – to the columns that ran three years ago.

This story is a complicated one involving a forgotten man, the son he never knew, and relentless searchers in Seattle and Spokane.

Ultimately, though, it’s a simple story of gratitude.

“It’s beyond coincidence,” believes Martha Lou Wheatley-Billeter, a Spokane County employee who helped organize the memorial service.

“Personally, I think grace was involved, and for every Jane and John Doe out there, I wish that their (mysteries) are eventually solved, too.”

The father

Michael Keith Roberts was born Jan. 22, 1953, at Tacoma General Hospital, to a 19-year-old named Olga. His biological father died when Roberts was young.

Roberts was raised by a stepfather, and Olga had another boy and a girl with the man, whose last name was Cole.

In 1974, when Roberts was 21, he was living in Denver with several other young people. He had long hair, a thick beard. He played guitar and worked as a dishwasher.

At a Lynyrd Skynyrd concert, he met Kristina, a 16-year-old runaway from Aurora, Colo. He invited her to live with him.

“He wanted to be a rock star,” Kristina Smith, now 51, said in a recent interview from her Amelia Island, Fla., home. “He had the hair, but he didn’t have the talent.”

In early 1975, Smith and Roberts traveled to Bainbridge Island, Wash., where Roberts’ family lived.

“He couldn’t wait to see his mom,” Smith remembers. “She adored him.”

Soon after meeting Roberts’ family, Smith flew back to Aurora, her runaway days over.

The known facts of Roberts’ life are sketchy between age 22 – when Smith last saw him and when his family apparently lost track of him, too – and age 30, when he was found dead in Spokane.

Public records indicate he enlisted in the Navy but was medically discharged. He was arrested in Colorado in 1978 after acting strangely outside a doughnut shop.

How Roberts ended up a transient in Spokane in 1983 – undernourished, possibly mentally ill, estranged from his family – remains a mystery. Roberts died all alone, not even knowing he fathered a son.

The son

Smith arrived back in Aurora, pregnant by Roberts. She didn’t tell Roberts because “he was nice, but he was different. He was five years older than me but less mature.”

While Smith was pregnant, she fell in love with, and ultimately married, a man whose family said they would embrace Smith’s baby as their own.

The man’s mother requested that everyone keep secret the true identity of the baby’s father, so the child would never feel different. Everyone agreed.

Zak Gilbert was born Oct. 6, 1975.

“Zak was the light of all our lives,” Smith says.

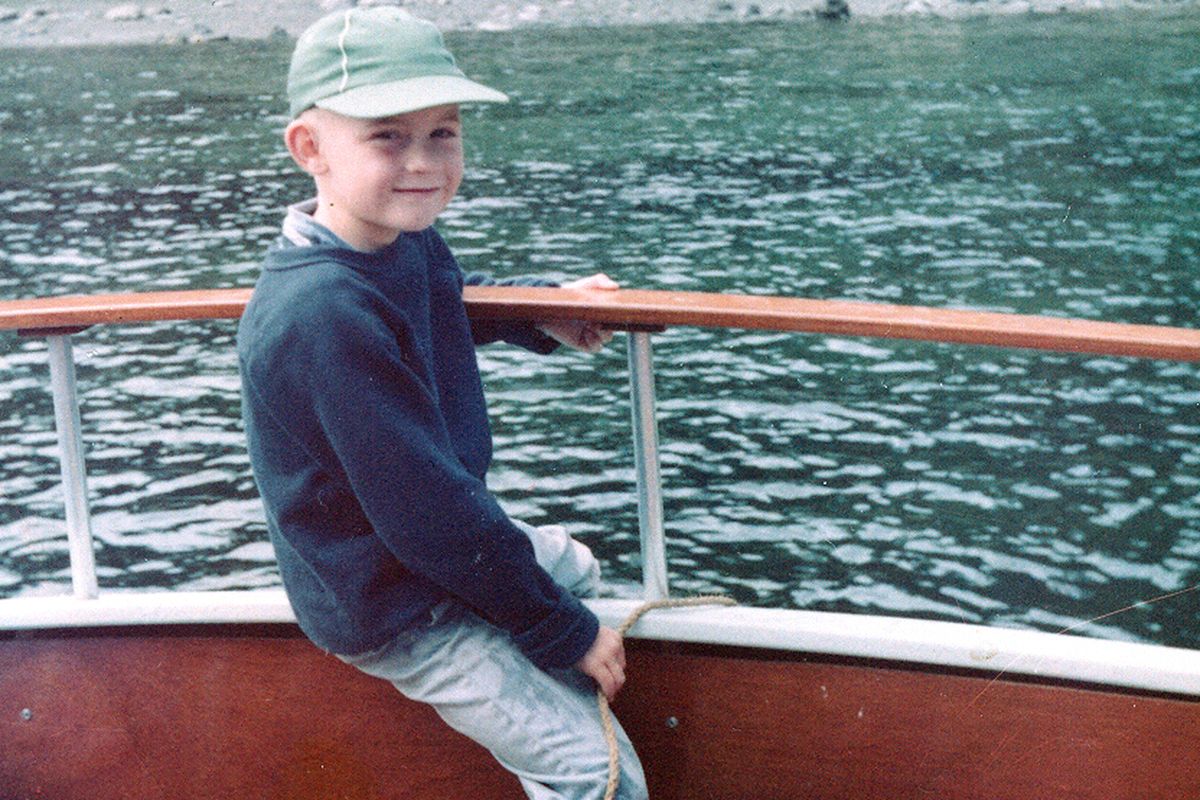

He was a shy kid, totally into sports, a boy who looked up to his father. The grandmother who safeguarded the secret died in 1995, when Gilbert was 19.

Gilbert remembers that his father “grabbed me by the hand and started crying. He said, ‘I’m not your biological father.’ ”

He then told him the story, and Gilbert’s mother filled in more details, including that she didn’t know where Roberts was, but she would help Gilbert find him.

Gilbert put the search on hold to finish college at the University of Colorado, and then he got busy building an impressive career. He worked in public relations for the Green Bay Packers, and now is director of media relations for Colorado State University’s athletic department.

During that busy time, he also got married and he and his wife, Jennifer, had two children, Ashlynn and Braden.

The searchers

Six years ago, Gilbert’s search began. From his mother, he knew that Cole was the last name of Roberts’ stepfather. He knew the family had once lived on Bainbridge Island.

Gilbert located a Bryan Gunnar Cole, a documentary filmmaker who grew up on Bainbridge Island. No relation, but Cole’s aunt worked at the Seattle Public Library and perhaps she could help, Cole said.

That woman, Clarice Cole Wilson, did some digging and then asked her friend, Sarah Little, for help.

Little teaches a genealogy and family history class at the University of Washington and specializes in tracking people. She agreed to help Gilbert, because “I always think people should know their roots. He seemed so genuine. Something tugged at me.”

Soon, Little had found and talked with Roberts’ stepfather and tracked down Roberts’ half-siblings – Gilbert’s aunts and uncles. But she found no trace of Roberts.

In 2006, Gilbert traveled to Western Washington and met Little.

He also met his uncle and talked on the phone with his aunt, and he saw – for the first time – several photos of Roberts, and Roberts’ mother, Olga.

“He looked just like my son,” Gilbert says of Roberts, “And Olga looked similar to my daughter.”

He left Seattle with many questions answered, except the biggest one: Was his dad dead or alive?

“Sarah’s theory was that he died a homeless person, because he left no paper trail,” Gilbert says.

In 2006, as Gilbert filled in the blanks in his biological father’s early life, Spokane County medical staffers were researching the end of it. They were looking into old cases and ran the 1983 John Doe’s fingerprints through a modern national data base.

Bingo! Michael Keith Roberts.

Their searching eventually led to Roberts’ stepfather. Olga was dead, he told them, and he didn’t care what they did with his stepson’s remains.

So county staffers contributed to a headstone and held a public service July 26, 2006 at Fairmount Memorial Park.

Three years passed. Gilbert’s biggest question remained unanswered.

“Out of the blue, this lady called me and said she was Olga’s sister in British Columbia,” he recalls. “She said, ‘You know what happened to your dad, right?’

“I said, ‘No, we haven’t found any trace.’ She said, ‘Well, he died in Spokane in the 1980s.’ ”

Olga’s sister told him about the 2006 Spokesman-Review columns, and within seconds, Gilbert found them on the Internet.

It was June 14, 2009 – 26 years to the day that Roberts was found dead in downtown Spokane.

The gratitude

After all the work they put into identifying Roberts in 2006, medical examiner staffers felt disappointed about the indifferent reaction by his stepfather.

“Legally, the stepfather isn’t part of this anymore,” says Lorrie Hegewald, deputy medical investigator. “This gives the son the right to exhume his father and bury him next to him.

“Even if he doesn’t want to do that, that’s OK. But the thing is he cares.”

Dr. Sally Aiken, county medical examiner, feels grateful her staff relentlessly pursued the identification of the 1983 John Doe.

This case reveals that “you don’t ever know the consequences of identifying a person,” Aiken says.

Gilbert’s mother, Smith, says, “Thank you from the bottom of my heart to the whole community of Spokane.”

Three years ago, Gilbert and his wife adopted baby Caitlynn. She will grow up never knowing her biological father, and Gilbert feels grateful that he’ll truly understand.

Gilbert is thankful for the Seattle searchers, especially Sarah Little. And, above all, for the Spokane County medical examiner’s staff.

“They were searching because they believe every person deserves an identity,” he says. “They assumed there was someone out there who cared about him. It turned out to be me.”