Horror stories: Writing children’s books is a hit or miss

Pretend for a moment that you’re 3 years old again, curled in your mother’s lap at bedtime. Warmth and sleep descend like steam in the bathroom.

Mom reads gently:

“Goodnight comb,

Goodnight brush,

Goodnight nobody,

Goodnight mush.

And goodnight to the old lady whispering ‘hush.’ “

It’s from the beloved “Goodnight Moon” by Margaret Wise Brown. And it’s so beautiful, so lyric, so simple that it seems effortless.

And that’s the problem.

It seems everyone who has kids, knows kids or who was a kid believes that he or she can write a children’s book.

“I think most adults think that writing for kids should be easy,” says Kathy Englehart, librarian at Hathaway Brown School in Shaker Heights, Ohio, and a frequent reviewer of kids books. “That you should just be able to write down a simple story and it will work for children. But that’s not usually the case. … I think it’s probably the hardest writing there is.”

Because so many folks already seem to believe they know how to write a kids book, perhaps it’s time to tell them how not to do it. How not to write a good children’s book.

Step 1: Be a celebrity.

Let’s say you’ve made a name for yourself by acting, singing country songs or rolling onstage in cone-shaped C-cups. You are now qualified to write a mediocre kids book.

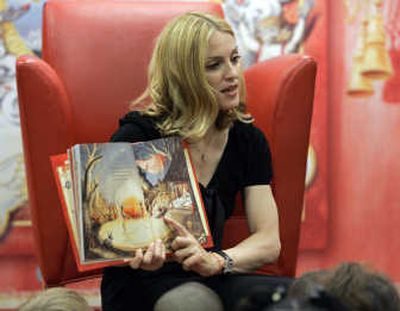

The list of celeb kids authors includes (but is hardly limited to) Billy Crystal, LeAnn Rimes, Madonna, Jerry Seinfeld, Jay Leno, Whoopi Goldberg. Critics have panned virtually all of their efforts.

Celebrity books often follow all the steps of how not to write kids books: They are preachy, wordy, syrupy, condescending and written for the parents, not the kids. (Crystal’s book, “I Already Know I Love You,” is actually a first-person story written from a grandfather’s point of view.)

Step 2: Have a moral, and preach it.

Children should be reading books that deliver a strong and not-so-subtle lesson of right and wrong, good and bad, how and how not to behave. Right?

Ummm. … that’s called a “lecture,” and it’s a sure way for kids to end up using your book as a Frisbee.

That’s not to say that kids books shouldn’t offer a learning experience, says Leonard Marcus, a children’s book historian, critic and author of “A Caldecott Celebration: Seven Artists and their Paths to the Caldecott Medal.”

“A lot of the great books really do have something to teach,” he says, “but they do it in an invisible way and you’re never made to feel that’s what the book is there for.”

Marcus cites Judy Blume’s “Fudge” series. While children crack up at the antics, they encounter subtle life lessons about their relationships and emotions.

Step 3: Let the words flow … and flow.

Part of the achievement of that soothing classic “Goodnight Moon” is that it has only 130 words. That’s how many words appear on the first page of Madonna’s “Mr. Peabody’s Apples.”

Great children’s books are simple, but not simplistic. The text seems distilled to its essence.

“Show me what’s happening, but don’t take a paragraph to tell me,” says Barbara Barstow, retired head of youth services at Ohio’s Cuyahoga County Public Library. “I learn better, I listen better, I become more involved when I actually participate in the discovery.”

Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are” is remembered for its amazing creatures. But its text, only 10 sentences, does not waste any words describing them. The pictures do the work.

Step 4: Treat the kids like children.

If you assume you need to explain everything, in easy words, and that kids should be sheltered from the realities of our harsh world, your book will surely be shelved under the F’s – for forgettable.

“The great children’s books imply respect for the young reader,” says Marcus. “They do not reach for the lowest common denominator.”

Consider “Charlotte’s Web,” the masterpiece by E.B. White. Charlotte the spider has a big vocabulary, weaving words like “humble,” “radiant” and “terrific” into her web.

“Wilbur the little pig doesn’t know any of those words,” says Marcus. “Wilbur will say, ‘What does that mean?’ And then Charlotte will explain it.

“The reader gets to find out without having to feel stupid for not knowing the answer.”

Good writers don’t sugarcoat childhood, either. They are honest about emotions. They know that young people don’t live in the nostalgic world of our memories, but in a world where they get angry, sad, hurt.

Step 5: Write for the parents.

Often, a grown-up will fall in love with a children’s book at the bookstore or library and then wonder why their kid or grandkid makes that finger-down-the-throat motion when they hear it read at home.

Most likely, the author has succeeded in making it all about the adults and not the kids.

“Writing for kids isn’t about you, it’s about them,” children’s author Jon Scieszka (“The Stinky Cheese Man”) told NPR a few years back. “Like a good teacher or a good parent, you have to give up always being the one in the spotlight. That’s a tough stretch for a lot of writers.”

Quite simply, kids need to see themselves in their books, not their folks.

One of the best examples is Ezra Jack Keats’ “The Snowy Day,” the classic story of a kid exploring the world after a snowfall.

“That’s just a regular child doing regular-child things,” says Englehart.