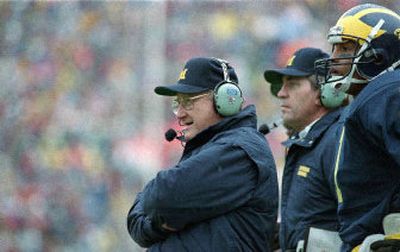

Bo loved game till end

DETROIT – The end of his life was coming. They could see that as they gathered around Tom Slade’s bed. This was eight days ago. Slade, the quarterback of Michigan’s 1971 Rose Bowl team, was about to succumb to cancer.

Bo Schembechler was there. Schembechler and another former Wolverine, Fritz Seyferth, started talking about Slade, who had been Bo’s dentist for many years. Slade had all the details worked out for after he died – the funeral arrangements, everything. He was prepared.

Schembechler was only a few weeks removed from his latest health scare. Thirty-seven years had passed since his first heart attack; 30 since his open-heart surgery; 19 since his second heart attack. His health had become progressively worse during the past several months.

Seyferth, who had become close to Bo, asked if the coach had made similar arrangements.

“I’m not gonna die,” Schembechler said.

Seven days later, he did.

He had said it with so much conviction – I’m not gonna die – that it was hard to doubt him, despite all the evidence. Isn’t that the strangest thing? He had dodged death for so many years, it was like he was immune to it.

Bo Schembechler might be the only person to die suddenly after a 37-year-battle with heart trouble.

Dan Dierdorf heard the news and immediately flew to Detroit. His wife, Debbie, said he didn’t even know why. After all these years, Dierdorf is still following Schembechler, no questions asked.

The tributes will pour in now, from coaches and political leaders and, most of all, his former players, men like Dierdorf. Here is one you haven’t heard.

In 1973, a Michigan freshman named David Turnley tried to walk on to the UM football team. After two or three weeks, Turnley realized he would probably never play a down at Michigan. There were too many talented players. He quit.

Turnley later became one of the world’s most respected photojournalists. He won a Pulitzer Prize for the Detroit Free Press in 1990, covered every major war of the 1980s and 1990s and worked on location in more than 70 countries. He spent extensive time with the Dalai Lama, Nelson Mandela, Muhammad Ali, Bill Clinton and Norman Schwarzkopf.

“I’ve been around a lot of generals,” Turnley said recently. “I’ve never been around anybody in any army that had his (Schembechler’s) kind of presence, that inspired his kind of authority.”

Schembechler had that presence right until the end. He had it Monday when he spoke to the media about the Michigan-Ohio State game. He had it Thursday when he addressed the Wolverines.

Gary Moeller said Friday that he heard Bo gave a phenomenal speech. But then, Bo never gave a bad speech.

Bo had postponed an appointment with his doctor, Kim Eagle, so he could talk to the team. He planned to see Eagle on Friday instead.

He never made it.

The timing would have ticked him off – nobody loved a rivalry more than Bo loved Michigan-OSU. In so many ways, he lived for it. Bo’s old coach and rival, Woody Hayes, lost some of his passion for the game after he retired – the commercialization of the game was too much for Hayes to bear.

Schembechler was different. He watched every Michigan game. He watched all the other college games that he could.

He watched the NFL from 1 p.m. Sunday into the night.

A few months ago, as I sat in his office for an interview, Bo looked at the clock and said he had to go.

Practice was about to start.

He and Seyferth were writing a book with Eagle, “Heart of a Champion,” about his miraculous medical life. They were supposed to meet Monday to talk about the latest chapter.

“Let’s not do it,” Schembechler told Seyferth.

Not now? Or not ever?

“Not this week,” he said. “This is Ohio State week.”