Exit 289: Schwan’s driver’s death delivers a sense of loss

The wife of fallen hunter Nate Swagel met their next-door neighbor last Thursday to empty the Cabela’s pack that had sat undisturbed since the 49-year-old was found on Monumental Mountain dead from hypothermia.

They were looking for answers, something tucked away with Nate’s hunting knife, rifle rounds and fire starter that would explain why he didn’t make it home Oct. 17. And just maybe Mari Swagel and Rory Pike hoped to find out why something so bad could happen to such a good man.

“We were neighbors for just about 15 years,” Pike said. “He was one of my best friends and I just keep saying I can’t believe it. It’s just a mystery.”

An experienced hunter, Nate had been lost in the Colville National Forest through six days of rain and snow before being found. While his death remains a mystery, his effect on the community has never been more clear.

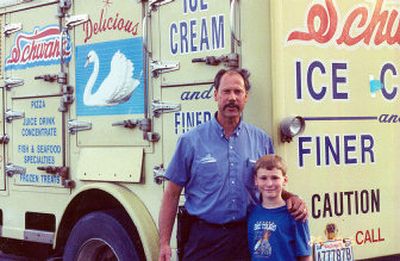

Hundreds of people will remember Nate as their Schwan’s man. Over the years, he’d driven his cream-colored delivery truck door to door from the South Hill to Mount Spokane and most recently Spokane Valley. His infectious smile was as recognizable as the large white bird on his company rig’s refrigerator door.

He didn’t just sell frozen food. Nate made the world a better place. If Valleyfest needed ice cream, Nate not only gave up his Saturday to sell it, but also paid for it and donated the proceeds to charity. If a shut-in on his route needed more food than Schwan’s had to offer, Nate stopped by the grocery store for milk and eggs. If someone’s freezer needed defrosting, Nate showed up on his day off with a couple coolers and buckets to get the job done.

“He just became like part of the family,” said John Weidinger of the delivery man who stopped by his Mount Spokane home every other week.

When the Mount Spokane firefighters had their Mother’s Day pancake breakfast, Nate not only donated 50 pounds of sausage, he also stood at the dining hall door handing out free ice cream bars to the moms.

“I was running his route a couple weeks ago and stopped at this big apartment complex,” said Kevin Lacefield, Nate’s supervisor. “All the kids hanging out came up and it was ‘we lost our Nate,’ not we lost our Schwan’s man. ‘We lost our Nate.’ “

No particular customer saw Nate more than once every two weeks, but the blue-uniformed salesman stopped at 100 houses a day, working one 20-block by 30-block area at a time. His workday started at 9 a.m. and seldom ended earlier than 9 p.m. These days, there are so many dual income families with empty driveways in the middle of the day that a salesman has to work well into the night to catch everyone, Lacefield said. Nate would sell to retirees and office pools during the day, then retrace his route after sundown looking for working families he might have missed. His own wife and daughter waited for him at home.

“Sometimes we’d talk when he got home from work, sometimes I’d be asleep when he got home,” said Mari Swagel. “It was a hard job especially in the wintertime, working in the cold with a refrigerated truck.”

Mari’s husband took the job with Schwan’s about 12 years ago to stay in town with his wife and daughter. Until then, Nate had worked for several oil and gas drilling companies, traveling from Alaska to Texas. He’d even spent a year managing a research camp at Palmer Station, Antarctica.

Schwan’s was a better job, allowing Nate to spend weekends with his family and even catch his daughter’s softball games, provided the games were played in Spokane Valley where he could pull his work truck into the parking lot and watch from afar. He strung the minutes of his day together like a puzzle, yet never forgot to show interest in the folks with whom he dealt.

“He wasn’t one of those kinds of guys who stand at the door clicking their little screen asking, ‘Do you want something else? Do you want something else?’ ” said Bonnie Morse, a Spokane Valley customer. “He always acted like he had all the time in the world.”

When Morse’s young grandchild, Audrey Schmitt, had open-heart surgery, Nate tucked a box of miniature ice cream sandwiches in with her order without mentioning it or putting it on the family’s bill.

This is the week Nate’s special touch will be missed. He always remembered that the family needed a frozen apple pie for Thanksgiving dinner even when Bonnie forgot. She’d walk out to the garage, lift the freezer lid and the pie would be waiting, right on top.