Nearly a century old, the Monroe Street Bridge reopens this weekend, sturdy enough to carry us for the next 75 years

The Monroe Street Bridge has inspired artists and lovers, served as a dramatic backdrop for public declarations and private whispers, seen much death and even new life. The mammoth, 94-year-old concrete Monroe Street Bridge has borne witness to Spokane history from the Roaring ‘20s, through the Great Depression, World War II, Expo ‘74 and beyond. But by the turn of the 21st century, years of spraying water and pounding traffic had battered the bridge to just a shadow of its former glory. This weekend Spokane will celebrate the bridge’s rebirth as it reopens after a 2½-year restoration project that stripped the structure down to its bare bones and rebuilt it sturdy enough to last another 75 years.

The same yet different

It’s easy to see the bridge in a different light today, thanks to the new fixtures.

Gone are the broken bison skulls, replaced with detailed copies of the originals. Cracked columns and spandrel arches have been replaced with new concrete.

The bridge stayed true to its original design to preserve its historic landmark status, but several changes were allowed to preserve it for future generations.

The four sidewalk pavilions, for example, were altered for their own protection. Though they look the same, construction crews bumped them out from the roadway.

In the previous configuration the skull sculptures protruded into the traffic lanes, leaving them vulnerable to run-ins with large trucks. Such collisions caused considerable damage to the skulls, even knocking some down over the years.

New lights actually give the bridge a more historic feel.

Engineers originally hoped to install the same kinds of lights first used — brass bottoms topped with large glass globes — but the $1 million cost was too high, and they wouldn’t have cast enough light to meet safety standards, said Steve Shrope, of David Evans and Associates, the principal engineer. City officials replaced those early lights after only a few years because of the high rate of vandalism.

Shrope and others decided to use lights similar to those installed later on the bridge. They now continue over to the new Spokane Falls promenade as well.

Crews also replaced the ugly cement barrier between the sidewalks and traffic with attractive concrete and metal railings.

A small gap has been inserted between the sidewalk and railing to allow snow and water to escape. Pedestrians who used to be forced to wade ankle-deep through slushy water while crossing over will appreciate the difference.

“We want concrete”

Early Spokane residents had their own bridge issues.

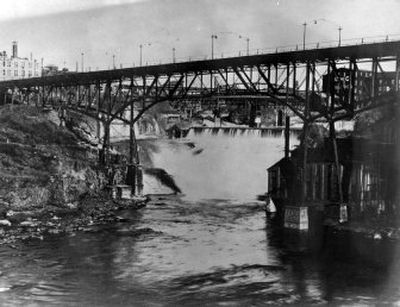

They endured two rickety bridges at the Monroe location prior to the concrete version — one wood, another steel.

But after an 1892 fire caused by a cable car destroyed the wooden bridge, and later, the steel bridge’s joints loosened to the point of near collapse, citizens demanded something safer. Reports from the time describe circus elephants balking when animal handlers tried to get them to cross over the steel bridge. Even they knew it was unsafe.

A newspaper editorial from the time said city officials turned deaf ears to the public’s cries for a concrete bridge. But public opinion eventually swayed city leaders and construction on the concrete Monroe Street Bridge began in 1909.

“I can assure the public that when the work is completed the bridge will stand as a model for years to come,” said Spokane Mayor N.S. Pratt in an April 30, 1910 Spokane Daily Chronicle article.

City Engineer J.C. Ralston essentially stole the bridge design, which is nearly identical to that of the Rocky River Bridge in Cleveland, Ohio, said Shrope. But there was one important distinction — the Monroe Street Bridge’s central arch is one foot longer.

That extra foot made it the longest concrete arch in the country at the time, and the third-largest in the world.

It held that record for less than a year, but ticked off Cuyahoga County, Ohio, officials enough that they unsuccessfully sued Spokane for $15,000 for copying their bridge.

Skeleton aside, the bridge’s artistic elements, including the famous pavilions sprouting bison skulls and the chain-link railing decoration, were Spokane’s own, designed by famed Spokane architect Kirtland Cutter.

The pavilions almost didn’t make the cut when city leaders objected to the arches on the grounds they would “harbor hold-ups and spooning couples.”

Spooning couples weren’t as much a problem as people committing suicide. According to newspaper accounts over the years, at least 43 people died jumping over the side, but there were likely many more. At least 10 people survived the fall.

And other tragedies also occurred on the bridge. A married couple died in 1974 when their station wagon crashed through the railing and plummeted off the bridge.

Concrete blocks known as “Jersey barriers” were installed between the traffic lanes and sidewalks after a toddler was killed in 1984 when a driver jumped the curb, hitting the 18-month-old’s stroller.

The slow decay

Though citizens were clamoring for sturdy, concrete bridges in the early 1900s, by 1979, the Monroe Street Bridge was showing its age.

Chuck Zinn was driving across the bridge that year when the front end of his car slid into a large hole caused by the collapse of a 40-square-foot chunk of the decking.

In the ensuing years, the city repaired holes, replaced the asphalt and patched the bridge’s ever-emerging cracks.

Still, the good times weren’t completely over. In 1994 the bridge was site of the birth of a healthy baby girl as her parents raced to the hospital in their Chevy Cavalier.

But by 2002 it became apparent that the bridge itself was dying and small fixes would no longer be enough.

An inspection revealed cracked columns, crumbling concrete and rusting reinforcements.

Buses and large trucks were forced off the bridge because of weight restrictions, and then-City Councilwoman Roberta Greene described the situation as “scary.”

It was time for drastic measures. Either the bridge had to be torn down or it had to be rebuilt.

But the city couldn’t bear to tear down this structure at its heart, so it launched an ambitious effort to restore the Monroe Street Bridge to its former glory.

Workers on the edge

Construction supervisors were acutely aware of the dangers of working on a structure 136 feet above the Spokane River.

After all, two men died during construction of the original concrete bridge. Several workers were injured when a freak windstorm blew down the wooden scaffolding used in the 1910 building project. Contrary to some recent histories of the bridge, no one was killed in that accident; the two men who died were killed in separate incidents. And in a 1911 near-tragedy, a cable broke sending timbers and chains flying, narrowly missing a dozen or more workers.

Such accidents were prevented during restoration by strict adherence to safety rules.

Workers were strapped into safety harnesses and attached to secured lines. Anyone who fell off the bridge wasn’t falling down into the river, said Project Superintendent Brad Elfring, who headed up contractor Wildish Co. operations.

The contractor solicited several safety consultants up front. One told Elfring not to bother with the cable typically strung across a river during bridge projects. Such cables are used to catch anyone who falls as they are swept downstream. Because of the height and hazardous conditions below, if anyone fell in, there would be no rescue operation, only a recovery operation, Elfring was told.

“That woke everybody up,” he said.

The safety preparation paid off, and no one was seriously injured during bridge restoration.

Late but under budget

The bridge originally was scheduled to reopen in May or June, but several problems delayed progress.

Chief among them was the discovery that a main pier on the north side of the bridge was hollow.

Engineers had planned to simply fill any cracks on the pier and move on, but its lack of solidity forced crews to grind it down and then rebuild it.

Officials feared that the south pier would have similar problems, but were fortunate to find that pier, built at a later date, was solid.

Even with complications, the Monroe Street Bridge was renovated for about $18 million, $2 million less than budgeted.

“We’re all euphoric over how well it’s gone,” said Shrope.

‘Everybody has a story’

Those who worked on the bridge said they were lucky to be a part of preserving Spokane’s history.

Elfring marveled at the engineering that had gone on almost a century before his crews began their work. A bridge built in the age of trolley cars and horse and buggies can carry city buses and semis today.

“I can’t believe they had the forward-thinking vision to see what we’d be putting on the roads now,” he said.

The bridge’s endurance has made it a fixture in Spokane life.

As he worked on designing and managing the restoration, Shrope was regularly regaled with tales from local residents, eager to explain their connection to the bridge.

“Everybody has a story about it,” Shrope said. “Everybody owns a piece of it.”