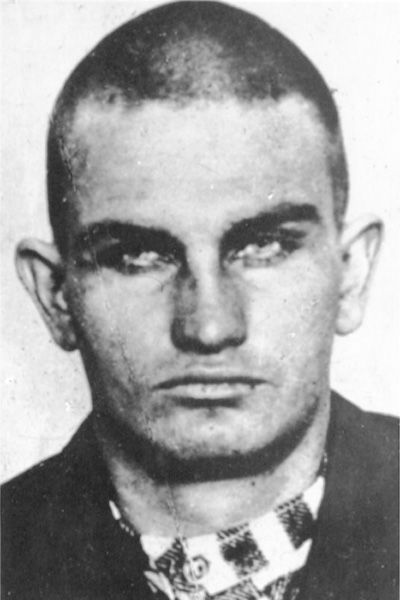

The outlaw Harry Tracy

A century ago, a convicted killer escaped from an Oregon penitentiary and went on a two-month rampage of terror across the Northwest, shooting down eight men along the way.

Harry Tracy was the villain of two popular stage melodramas.

He was the main character in several silent movies.

He was immortalized in numerous lurid dime novels.

He was the title character of a 1983 movie starring Bruce Dern.

And this week at the Lincoln County Fair in Davenport, Wash., the Harry Tracy story comes alive one more time, 100 years to the month after his death. An Old West re-enactment group, the Legendary Characters of the Old West, will re-create the shootout that left Harry Tracy dead just a few miles from those fairgrounds.

As we creep into the 21st century, you might be forgiven for wondering: Harry who?

Virtually nobody in 1902 would have had to ask that question. For sheer notoriety, Harry Tracy was Ted Bundy, Robert Yates and O.J. Simpson all rolled into one, except in Harry’s case the nation wasn’t riveted by a chase in a Ford Bronco. The nation was riveted by a chase on a real bronco.

At one point, hundreds of lawmen, dozens of reporters, the U.S. Army and even the U.S. Navy were all frantically on the trail of Tracy. When he showed up in Seattle, the Seattle Times warned its citizens, “Jesse James, compared with Tracy, is a Sunday school teacher.”

The Northwest was particularly panicked by the story because Tracy seemed to show up in just about every corner of the region. After his final, highly publicized prison escape, he sneaked from Salem to Portland to Seattle to Bothell to Bainbridge Island to Kent to Auburn to Wenatchee to Almira and finally to a wheat farm just west of Davenport, where Tracy was cornered by a posse behind a rock outcropping.

We’ll tell you what happened there in its proper place below. Suffice to say, it turned out to be Harry Tracy’s Last Stand.

Even today, Harry Tracy remains at least a minor tourist attraction in Lincoln County.

“We’ve had people come out and ask to look at the rock,” said Karen Cole, who now owns the ranch with her husband, Everett Cole. “It goes in streaks. We might not have anybody for a couple of years, and then - boom - we’ll have six or seven. Once an entire Greyhound bus full of people came out from the National Outlaws and Lawmen Association.”

The Lincoln County Historical Society gets the occasional Tracy visitor, too. It owns the death mask of Harry Tracy, a plaster cast made by the undertaker, which is presently on loan to the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture in Spokane. So if you visit the “Hometowns” exhibit, the visage of Tracy glowers down upon you.

What did Tracy do to deserve all of this notoriety?

The short answer is, he killed somewhere around eight people and robbed many others.

However, what he did best was escape from prison. He escaped four times, and all of his murders stemmed directly or indirectly from his escapes.

He started out as a Wisconsin logger and by the age of 21 had drifted west to a logging camp on Loon Lake north of Spokane (his cabin there later became yet another Tracy tourist attraction). Then he drifted to Montana and Utah and at some point decided stealing was easier than working.

He broke into a house in Provo, Utah, in 1897 and stole some goods. Four days later, he found himself in the Utah State Penitentiary.

He escaped just a few months later while out digging a ditch on a work crew. He made a replica of a revolver out of wood and tinfoil, threatened a guard, wrenched the shotgun away from him, and lit out for Vernal, Utah.

Tracy was a fugitive from this point on, and his method of survival took on a familiar pattern. He would enter a house at gunpoint and tell his victims to supply him with food, drink, shelter and transportation. He always told them that he wouldn’t hurt them, and he apparently never did (his murder victims were almost all prison guards and other pursuers). He was usually courteous, or at least as courteous as a man brandishing a revolver can be. He later bragged that he was particularly proud that he had never harmed a woman.

He and some other escapees made it to Powder Springs, Wyo., the lair of the infamous Wild Bunch. When a posse came looking for a fellow badman, Tracy or one of his companions shot one of the posse members dead.

Another posse tracked Tracy and his pals a few days later and arrested them on a Colorado hillside.

According to Jim Dullenty’s well-researched 1989 book, “Harry Tracy: The Last Desperado” (the source of much of this chronology), Tracy offered the deputy a deal.

“Give me a cup of coffee, a fresh horse and 25 yards head start, and I won’t bother you no more,” he said.

No deal. Tracy and his cohorts were charged with murder and taken to the Routt County Jail in Hahn’s Peak, Colo. They weren’t there for long.

Two weeks later, Tracy and his pal David Lant overpowered the sheriff, took the keys and vanished. They were arrested the next day as they attempted to hitch a ride on a stage sleigh in the snowy mountain country. Unfortunately for them, it turned out to be the stage sleigh the sheriff was riding in, on the way to round up a posse.

The sheriff shackled them and took them to the supposedly more secure Pitkin County Jail in Aspen. Once again, they escaped after nearly beating a guard to death.

Lant vanished from history at this point, but Tracy was just beginning his outlaw career. He made it all the way to Seattle, where he met up with another outlaw named David Merrill. They committed several robberies and then moved south to Portland, where they became known as the Black Mackinaw Bandits because of their habit of holding up downtown saloons, butcher shops and grocery stores wearing black mackinaw raincoats.

Tracy apparently fancied himself a Jesse James figure, in a time when dime novels were romanticizing the fading era of Western bandits. He even wrote a poem about himself while in that Aspen jail. It mocked the courage of the lawmen who had tried, and failed, to capture him after his first escape.

One verse went like this:

Now just one word to citessons (citizens),

Who for protection cry,

Just vote for braver officers,

When the swallows homeward fly.’

Yet some Portland detectives showed plenty of bravery when they raided Merrill’s house, arrested him, and laid in wait for Tracy to return to the house. A gunfight ensued, with a bullet ricocheting off Tracy’s skull as he tried to flee. The wound was superficial, but Tracy was captured.

He and Merrill were taken to Portland’s Kelly Butte Jail. Two months later Tracy nearly pulled off another escape. Someone smuggled a pistol to him, but after a brief shootout in the jail corridor, he and Merrill surrendered. Tracy ended up with a 20-year sentence for assault and robbery (compounded by attempted escape) and was sent with Merrill to the Oregon State Penitentiary in Salem.

It took three years, but he and Merrill escaped from that one, too. Someone apparently smuggled two rifles and a sack of ammunition over the wall. Tracy and Merrill shot two guards and a fellow inmate, and then kept up a fusillade as they calmly lifted a ladder to the wall and jumped.

This is where the Harry Tracy saga became national news. About 250 lawmen and militiamen - not to mention dozens of bloodhounds, reporters and various free-lance bounty hunters - fanned out over the Salem area, but Tracy and Merrill got away by commandeering a buggy and then stopping at farmhouses for lunch and dinner.

They reached the outskirts of Portland and started reading about their exploits in the Portland papers. Reporters and photographers, including some from the East Coast, were among those in pursuit.

Tracy and Merrill hijacked a boat and forced its occupants to row them across the Columbia into Washington.

Somewhere near Napavine, Wash., Tracy rid himself of his partner Merrill by shooting him three times. He told various stories of why he did it: He thought Merrill had betrayed him in Portland; he was jealous because Merrill was getting too much credit in the press; or he thought Merrill had lost his nerve. According to another story, the two agreed to a duel, but Tracy turned on Merrill and plugged him after eight paces instead of 10.

In any case, Tracy was now on his own. He decided, against all reason, to head for Seattle. He walked into an Olympia oyster shanty and commandeered a motor launch and a crew of four.

He steamed all the way to Seattle, got off the boat, promised the crew he’d pay them back some day, and walked into Ballard. The Seattle papers were filled with sensational stories about the arrival of a desperado “with no equal in the criminal lore of the country.”

Tracy played his role well, terrorizing the Seattle-area citizenry for the next two weeks, walking into houses with gun drawn and saying, “I am Tracy.”

One Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter later said that several times he and another Seattle reporter placed themselves “in a position to be captured by the outlaw in order to get an interview from him.”

A posse and two Seattle newspaper reporters found him hiding behind a stump in Bothell, just north of Seattle, but he leapt out and shot one of the deputies dead.

The reporters got no interview. They threw themselves down in the long grass and were too frightened to move until he was long gone.

Tracy shot and killed two other lawmen when they tried to arrest him as he emerged from a Seattle home where he had sought refuge and a home-cooked meal.

He commandeered another boat to Bainbridge Island and then circled back to West Seattle. At this point, even the U.S. Navy was in the hunt, sending a flotilla out to look for him. He headed south to Renton, Kent and Black Diamond, where he terrorized several farm families but never hurt them.

He made his way over the Cascades, probably over Stampede pass, and stole a horse on the other side.

He rode into Wenatchee and, according to one report, called the King County sheriff by phone and taunted him.

Then he stole two horses from a rancher and took off for the east. Destination, he said, Hole-In-The-Wall, Wyo.

Somewhere in a high draw just west of Davenport, he was cooking dinner over a sagebrush fire when he saw young George Goldfinch, 21, a local ranch hand, riding past.

Tracy called to Goldfinch and told him to come over and have dinner. Goldfinch declined, saying he had already eaten.

When Tracy flashed a revolver, young Goldfinch later said he “thought better of the invitation and accepted.”

Tracy told him who he was and forced Goldfinch to take him to the nearest ranch, which was the Eddy ranch. Tracy told Goldfinch to “introduce” him to the Eddy brothers, which he did.

“The Eddy boys were not particularly glad to see him,” Goldfinch said. “But they made no objection to entertaining him, for his revolver was in sight all the time and none of us knew when he might use it on us.”

He allowed Goldfinch to go home after warning him he would kill him and the Eddys if he told the sheriff.

That first night, Goldfinch didn’t tell. But he came back the next day to see if the Eddys were still alive and if Tracy was still there.

Tracy was busy helping the Eddys do some barn repairs. This time, Goldfinch went back to Davenport and phoned the sheriff.

Someone else heard Goldfinch’s message and alerted a posse from Creston, the town just west of Davenport.

A five-man Creston posse arrived at the Eddy ranch. Tracy saw them, made a run for the barn, grabbed his rifle, and darted to a haystack 20 feet away. The posse opened fire but missed.

Then Tracy sprinted to the big basalt outcropping known ever since as Tracy Rock.

The Spokesman-Review described it this way: “He had to pass in full view of the posse, which fired again as he tried to reach the rock. One shot must have taken effect then, for he leaped headlong into the wheat field which lay below the rock. … Presently they saw him sitting up and doing what appeared to be dressing a wounded leg.”

A few more shots were exchanged. However, Tracy was apparently losing blood fast from two bullets in the leg. He tried to crawl through the wheat field but made it only about 75 yards. The posse, which was now joined by a larger posse from Davenport and a contingent of reporters, waited him out as dusk fell.

Not long after, they heard a gunshot. Still not wanting to approach this desperate gunman, they didn’t creep up on the spot until dawn. There they found the famous Harry Tracy with his revolver still in hand.

He had shot himself through the eye, fulfilling his vow not to be taken alive.

The news of his demise spread all over the nation within hours. Reporters, lawmen and just plain gawkers descended on the small town of Davenport.

“The county undertaker put Tracy’s body on display on his front porch and charged the crowd five cents apiece to file by,” said Gary Schmauder, the Lincoln County Historical Society curator and secretary.

The crowd went on a frenzy of souvenir hunting.

“Locks of the outlaw’s hair, portions of clothes and ammunition disappeared almost in a twinkling,” said The Spokesman-Review. “Bloody portions were eagerly seized upon.”

A heated dispute broke out over the $4,100 reward money. The Creston posse ended up with the money; Goldfinch and the Davenport sheriff did not.

Dutch Jake, owner of the biggest gambling and music hall in Spokane, offered Goldfinch a stage “engagement,” although it is unclear if he ever accepted the offer.

Both the Spokane Chronicle and The Spokesman-Review devoted their entire front pages to Harry Tracy.

The Chronicle’s banner headline read, “Harry Tracy’s Race With Death Is Ended.”

But the plays, movies and dime novels were just beginning.

Jim Kershner can be reached at (509) 459-5493 or by e-mail at jimk@spokesman.com.