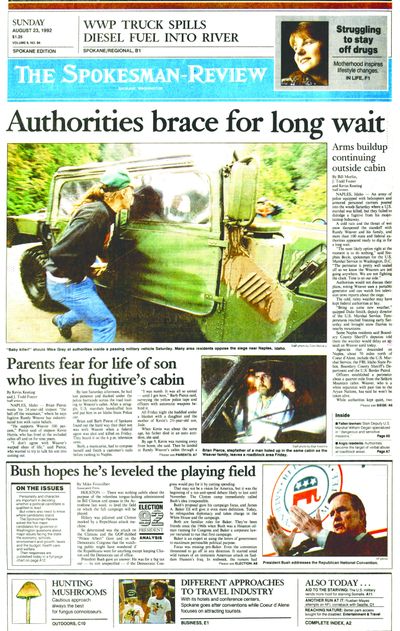

Authorities brace for long wait at Ruby Ridge as arms buildup continuing outside cabin

NAPLES, Idaho – An army of police equipped with helicopters and armored personnel carriers poured into the woods Saturday where a U.S. marshal was killed, but they failed to dislodge a fugitive from his mountaintop hideaway.

A cold rain and the threat of wet snow dampened the standoff with Randy Weaver and his family, and more than 100 state and federal authorities appeared ready to dig in for a long wait.

“The most likely option right at the moment is to do nothing,” said Stephen Boyle, spokesman for the U.S. Marshal Service in Washington, D.C. “The perimeter is pretty well sealed off so we know the Weavers are not going anywhere. We are not fighting the clock. Time is on our side.”

Authorities would not discuss their plans, noting Weaver uses a portable generator and can watch live television news reports about the siege.

The cold, rainy weather may have kept federal authorities at bay.

“Bring us some new weather,” quipped Duke Smith, deputy director of the U.S. Marshal Service. Temperatures reached freezing early Saturday and brought snow flurries to nearby mountains.

Some Naples residents said Boundary County Sheriff’s deputies told them the weather would delay an assault on Weaver until today.

Agencies that descended on Naples, about 70 miles north of Coeur d’Alene, include the U.S. Marshal Service, the FBI, Idaho State Police, Boundary County Sheriff’s Department and the U.S. Border Patrol.

Officers established a perimeter about a quarter-mile from the Selkirk Mountain cabin. Weaver, who is a white separatist with past ties to the Aryan Nations, has said he won’t be taken alive.

While authorities kept quiet, two dozen neighbors and friends of Weaver set up a protest line, face-to-face with federal marshals manning a roadblock. In a steady downpour, the protesters held signs saying, “Stop the Violence,” and “Leave Them Alone!” Another said, “Your Home Could Be Next.”

But it was clear from the assembled troops and their firepower that federal agents weren’t about to let Weaver continue thumbing his nose at the government as he was done for the last 20 months.

Weaver, his family and another man have been holed up in his self-sufficient cabin since January 1991, when Weaver failed to appear in U.S. District Court in Moscow, Idaho, on federal firearms charges.

On Friday morning, a team of six U.S. marshals conducting surveillance on the cabin were fired upon, and one marshal, 42-year-old William Degan, of Boston, was killed.

Two marshals escaped while three remained pinned down by sniper fire for about 12 hours. A special law enforcement team finally rescued the three and retrieved the body.

Authorities weren’t certain who fired the fatal shot, which reportedly rang out after Weaver’s dogs began barking at strangers near the property.

“This was a very dangerous and sensitive mission,” Thomas Nixon, the deputy marshal in the Boston office, told the Boston Globe. “(Degan) was selected to go up and retrieve vital intelligence on how we would extract the individual from that house. It was about to come to a head. That was the reason for sending him up there.”

Degan’s death brought an onslaught of federal agents that matches the December 1984 standoff involving Inland Northwest whit supremacist Bob Mathews, who ultimately died in a fiery shootout with the FBI on Whidbey Island.

At the roadblock just south of Bonners Ferry, spectators said the scene looked like something out of a “Rambo” movie.

And the townsfolk were anything but enthusiastic about the siege. Overnight, someone sprayed “Entering Dead Cop Zone” graffiti on a railroad underpass, just a short distance from the roadblock.

Residents evacuated from the area also complained about being kept from their homes.

“I’m wet, I’m cold and I want to go home,” said Lela Belmont, 32, who was evacuated along with about a dozen families who live on Ruby Creek Road below the Weaver fortress.

She said her husband, Home Reese, has been in a Spokane hospital after undergoing knee surgery and is due home Monday. “I have no idea where I’m supposed to go, what I’m supposed to do,” she said. “I’m a victim of all this.”

Lori Skinner, who lives below Weaver, said her horses and goats were famished and thirsty by the time authorities changed their mind and allowed her to return home for a while to care for them.

At midday, two armored personnel carriers roared down old Highway 2, past Deep Creek and up Ruby Creek Road, where a command post was established.

A telephone truck also went through the roadblock, leading to speculation that agents were attempting to establish a communications link with Weaver.

One scenario suggested agents would use an armored personnel carrier to take a phone to a location near the residence, which doesn’t have a telephone.

Marshals apparently hadn’t intended to attempt to arrest Weaver until sometime after Oct. 1., when additional funds become available with the start of a new budget year. But that plan was scuttled when the shooting occurred.

On Saturday, authorities also rebuffed attempts by Weaver’s friends, including Loren Jones, of LaClede, Idaho, who wanted to intervene and attempt to talk Weaver into surrendering.

“I can’t even get word up to the command post that I want to help, that I’m here, but yet I see them hauling in truckloads of (portable toilets) and other supplies,” Jones said.

He said Weaver served in Vietnam as an Army Special Forces soldier.

Jones said he also knows 24-year-old Kevin Harris, “who will stand by Randy because he knows Randy is in the right. Randy is right. The charge against him is 100 percent BS.”

Weaver was indicted in December 1990 on federal charges of making and possessing illegal firearms. An informant told authorities a year earlier that he bought two sawed-off shotguns from Weaver.

Harris has lived with the Weaver family for several years.

Weaver and his wife, Vicki, have four children, including an 8-month-old daughter.

The cabin has been supplied with food by friends who, in varying degrees, share Weaver’s white supremacist views about Jews, blacks and the federal government.

The cabin, built by Weaver over the past few years, is described as cozy and immaculate.

“It’s a rustic log cabin, everyone’s dream,” said Tom Linke, 40, who lives near Weaver.

The family also has a small trailer near the cabin and a gravity-fed water supply system.

The main floor is a large room, and there is a loft above where the children sleep, Linke said.